I’ve noticed a change in my student’s behaviour. They seem tired, down, and distracted. How can I help them? Get some ideas.

One of my colleagues confided in me that she was dealing with depression and having trouble learning music for her recital. How can I support her? Learn more.

I have depressive episodes sometimes, and lately I’m having more difficulty than usual absorbing things in my lessons. Is that weird? No! Learn more.

Introduction

Most of us have encountered mental health issues, whether in ourselves or our friends, students, and colleagues, and we know that their effects on our music-making can be profound and wide-reaching. Just as we strive to understand the physical issues that impact our playing, learning more about our mental health leaves us better equipped to find adaptations, solutions, and ways to heal.

In this blog post, let’s focus on depression. Approximately 11% of men and 16% of women in Canada will experience depression at some point in their lives (Government of Canada, 2009). To receive an official diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder or MDD, you must experience at least five out of nine possible symptoms. The most important indicators are depressed mood and loss of interest or pleasure in things you normally enjoy, but other signs can include irritable mood (especially in teenagers), dysregulated sleep, agitation, physical slowness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and more.

MDD occurs in what are called episodes—periods of at least two weeks, and often considerably longer, during which symptoms persist and interfere significantly with your daily life. For most people, the condition is recurrent, meaning that episodes come and go over time. To learn more about how psychologists diagnose depression, you can consult the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders directly (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

What does this have to do with music specifically? Several studies have found that psychological distress and mental health disorders are more prevalent among orchestral musicians than among the general population (Vaag et al., 2016; Voltmer et al., 2012), and an Australian study found depression symptoms in 32% of musicians sampled (Ackermann et al., 2014). There is also evidence that university music students with depression symptoms seek treatment significantly less often than the general student population (Wristen, 2013).

As musicians, it can be hard for us to admit that we are struggling, whether because we tell ourselves we should be happy doing what we love, or because of the stigma that still surrounds mental illness in many different situations. It’s important to understand, though, that depression is a very treatable medical condition. Having depression is not a sign of failure or weakness!

The more we understand depression, the more we can help ourselves, our friends, and our musical communities address the issue openly, developing tools that will help us no matter the state of our mental health.

So let’s talk about it.

Your brain on depression

There is no brain scan or laboratory test that can diagnose depression (DSM-5; APA, 2013), but depression does have real, biological impacts on the brain and how it functions. We simply need to understand that the brain is almost unimaginably complex, and while neuroscience has made many exciting advances, we are nowhere close to understanding all the neurological mechanics of human behavior.

To cope with this reality, Alan Watson outlines three primary levels of focus for study of the brain. First, we can look at individual brain cells and their connections; second, zooming out, we can observe areas of the brain that are most active during different types of thought and behavior; third, we can treat the brain as a black box, observing psychological responses to different without going into their underlying mechanics (Watson, 2009). The science of depression involves a lot of studying these different levels separately and gradually making inferences about how they are related.

BRAIN CELLS AND NEUROTRANSMITTERS

Let’s start with level one, the cellular level!

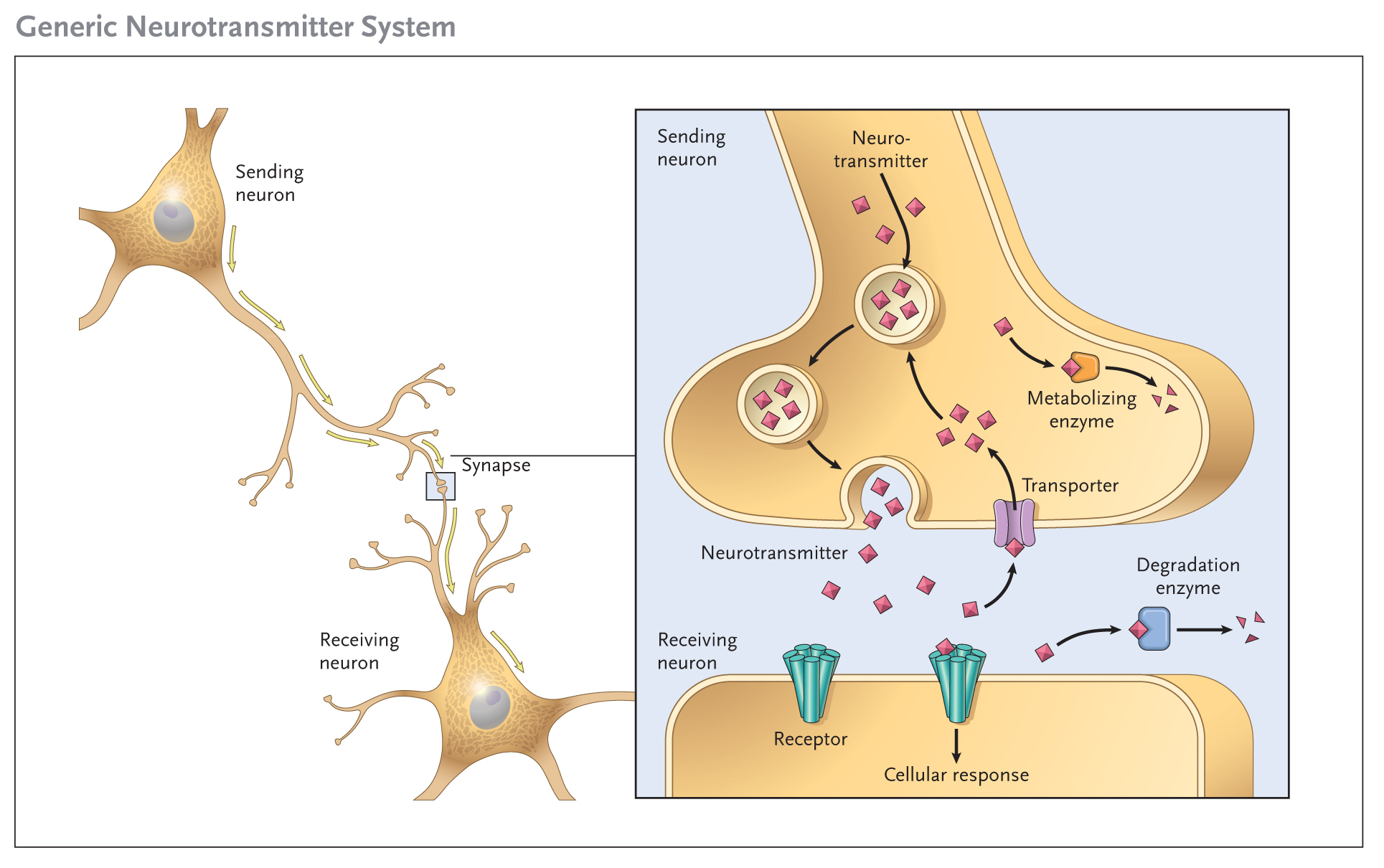

Information travels in the nervous system via neurons—cells that transmit electrical signals within the brain as well as between the brain and the tissues of the body. Neurons come into contact at tiny sites called synapses, of which there are at least 60 trillion in the brain alone (Watson, 2009)! There, the sending neuron will release neurotransmitters, which essentially increase or decrease the likelihood that the receiving neuron will fire an action potential or electrical signal towards other cells.

One key thing to understand for our purposes is that, once neurotransmitters have bonded with their corresponding receptors, they are released again—and there is nothing to prevent them from re-bonding with the receptor and continuing to affect synaptic activity unless they are broken down, transported away, or reabsorbed into the sending neuron.

The monoamine hypothesis is a theory for understanding depression that dates back to the 1950s. It suggests that depression is associated with a deficiency in transmission of a class of neurotransmitters called monoamines, include noradrenaline and more well-known hormones/neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine (Cosci and Chouinard, 2019). This hypothesis led to the development of common antidepressant medications such as SSRIs—Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Essentially, these interfere with the mechanisms that evacuate serotonin from the synapse, compensating for deficiency in transmission.

However, these days the consensus is that the monoamine hypothesis is not sufficient to understand something as complex and varied as depression. So let’s zoom out and move on to level two—studying activation of different areas of the brain!

AREAS OF THE BRAIN

The nervous system contains both white matter and gray matter. White matter is composed primarily of insulated axons, the long, thin “cable” parts of neurons that transmit electrical signals over considerable distances. Gray matter is composed primarily of neuron cell bodies and thus contains an extraordinary density of synapses, where neurons connect and communicate with each other. The outside of the brain is lined with gray matter; this is called the cerebral cortex (cortex is Latin for “bark of a tree”). Different areas of cortex are associated with different functions of the brain, although they function in complex networks and relationships. There are a few different visualizations of cerebral cortex in the table below—it’s the folded outer layer of the brain composed of gray matter.

Various neuroimaging techniques make it possible to study which areas of the brain are activated during different mental tasks and activities. In people with Major Depressive Disorder, some areas of the brain have been repeatedly found to show either reduced gray matter volume or decreased activity compared to the norm. Here is a brief overview based on Maletic et al., 2007.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Hippocampus”]

The hippocampus is associated, among other things, with the formation of long-term memories, recollection, and regulating emotion (especially in relation to memories).

In depressed people, it is consistently found to be smaller in volume; this can be an inherited trait and/or a change in adult life brought on by a depressive disorder.

Image generated by Life Science Databases(LSDB)., CC BY-SA 2.1 JP, via Wikimedia Commons. Click to see a larger version.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Prefrontal cortex”]

The prefrontal cortex (PMC) is a wide-ranging and complex area of the brain. It is usually associated primarily with executive function, roughly defined as planning and regulating thoughts and actions in order to achieve goals.

- The ventromedial (front, middle) PFC is associated with processing pain, aggression, sexual functioning, and eating behaviors.

- The dorsolateral (back, sides) PFC is associated with sustained attention and working memory.

This area of the brain has consistently shown either over- or under-activation with respect to healthy brains used for comparison. (Maletic et al., 2007).

- “Hyperactivity of the VMPFC is associated with enhanced sensitivity to pain, anxiety, depressive ruminations and tension.”

- “Hypoactivity [under-activation] of the DLFPC may produce psychomotor retardation, apathy, and deficits in attention and working memory.”

Learn more about the prefrontal cortex with 2-Minute Neuroscience on YouTube

[/tab]

[tab title=”Anterior cingular cortex”]

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is also part of the executive functioning network. It is involved in assessing emotional emotional information and monitoring the outcomes of actions.

In depressed people, this area shows reduced gray matter volume (that is, smaller size), as well as abnormal activation and dysfunctional communication with other regions of the brain, such as the amygdala, which is associated with emotional processing.

Image from Geoff B Hall, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

[/tab]

[/tabs]

And this is barely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the physiology of depression! Our understanding of depression is constantly evolving and linked to topics such as complex neural networks, the formation of new neurons in adult life, genetic factors, and chronic stress. That said, one important takeaway is that “as an integrated circuit, the prefrontal cortex, cingulate, amygdala, and hippocampus serves not only mood regulation, but also learning and contextual memory processes” (Maletic et al., 2007). Bearing in mind what we just learned, let’s go into the third level—the brain as a black box.

LEARNING WHILE DEPRESSED

When we know someone has major depressive disorder, what else can we gather about how their brains work by observing from the outside? And how does this relate to music education?

Naturally, symptoms like fatigue, low mood, and anhedonia (not finding pleasure in things) reduce our desire or our motivation to make music. But if it feels like your difficulties in lessons and practice sessions go beyond lack of motivation, you’re not alone—and you don’t need to be frustrated with yourself. Although cognition itself is a complex topic, numerous have found that people with MDD perform worse on tasks involving something called reinforcement learning.

Basically, when people with depression are given tasks that require them to make repeated choices and gradually learn which choices reward more, they perform worse than controls (the group without depression used for comparison)—they do not develop a bias for the more frequently rewarded option. This is partly because they don’t remember previous rewards as well (Rupprechter et al., 2018), which is consistent with the idea that depression impairs working memory and focus. Another study found that subjects with MDD did not learn as well from punishment—they did not develop a strong preference for no-punishment options (Mukherjee et al., 2020).

Let’s think about this about this outside the laboratory context. From the outside, it might seem like a depressed person is just consistently failing to make the choices that make them feel better or that help them get through work or school. But this is actually part of the condition. And although there aren’t yet any studies specifically addressing how depression affects the learning of a musical instrument, it’s not hard to imagine that impaired reinforcement learning would have an impact on the skill-building process.

[box title=”Get treatment! ” border_width=”5″ border_color=”#008000″ border_style=”solid” bg_color=”#C3FDB8″ align=”left”]Depression is a highly treatable condition! Many different types of support are available, any combination of which might work for you. Taking care of yourself through exercise, food, sleep, and interacting with others can make a huge difference. Psychotherapy can also be extremely helpful; therapists, psychologists, social workers, and other professionals can provide a safe space to express how you are feeling and help you develop the tools you need to recover. There are also many medication options available. Often, they are especially effective in combination with therapy!

When in doubt, talk to a healthcare professional. Depression is a real medical condition that deserves to be acknowledged and treated as such. Just helping someone—yourself included—seek out the care they need and offering them patience and kindness can be a powerful gesture! Here are a few resources to get your started:

- Depression | CAMH

- Depression – Mental Health Disorders | Merck Manuals Consumer Version

- Depression | Gouvernement du Québec (quebec.ca)

- Depression | Student Wellness Hub – McGill University

[/box]

Conversation starters

You don’t choose to be depressed, and while you can certainly seek out treatment, you can’t dictate the timeline of your recovery. In the meantime, music-making can be difficult. So what can you do?

To use the physical injury analogy again, ignoring pain during playing can lead to compensating in unhealthy ways and making the injury worse. Ignoring your mental health isn’t any better. Remember, you’re not a failure for feeling this way. In fact, this could be an opportunity to develop coping strategies that can help you no matter how your brain is working.

Take the following scenario. If it sounds familiar, remember to be kind to yourself!

You notice that playing a passage the way your teacher said was best doesn’t give you the satisfaction that it usually would. As you play it over and over, you can’t get the change to sink in even though you can hear and feel that it’s better that way. You feel like you’re getting nowhere, and you give up in frustration, dismissing the practice session as a waste of time. You tell yourself you’re not capable of improving, and the idea of practicing starts to make you feel increasingly guilty and tired.

Simply acknowledging your feelings can give you a sense of perspective. Here are some things you might notice in the hypothetical situation above.

- Reduced pleasure in things you used to enjoy, depressed or irritable mood, physical slowness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and feelings of worthlessness—all of these can be signs of Major Depressive Disorder. Even though it might not feel like it right now, these symptoms are treatable and can fade or disappear with time.

- Depression can make you more likely to discount, ignore, or forget past rewards (Rupprechter et al., 2018). This could be part of why you perceive that you are getting nowhere, but that doesn’t mean your practice session was a waste.

- Depression is associated with low expectations for the future (Rupprechter et al., 2018). While it’s normal to feel this way, it doesn’t mean that this is necessarily how the future will be.

Talking about the issue with your music teachers, mentors, and peers can also be very helpful. You don’t have to disclose any diagnoses or outside experiences if you don’t want to. Instead, focus on how your symptoms are affecting your music-making and ask for help developing alternate strategies. Here are some suggestions.

From a student’s perspective

A few days this last week, I’ve been too physically tired to play my instrument. Can we talk about ways to work on my music even when my energy is low?

I spoke to a doctor recently, and she told me that the fact that I haven’t been absorbing things as quickly could be related to an overall health issue. For now, I think a slow pace will be most effective.

My original goal was to have completely reworked this piece in the next month, but that doesn’t feel realistic anymore, and I’m finding it quite discouraging. Can you help me find a goal for the next week that feels more achievable?

From a teacher’s perspective

Some periods in my life just haven’t been well-suited to striving for technical achievement. Cultivating meaning and presence in daily practice sessions can be just as helpful, and set you up well to do great technical work later. If you like, we can focus our next few lessons on strategies for cultivating that positive relationship with practice. It’s not easy!

Let’s take a few minutes at the beginning of the lesson to find some routines and tricks to help you focus over short periods. It’s a useful way to practice when you don’t have much time, and some days everyone needs some help focusing their attention!

It can be really hard to notice improvements in our own playing. Let’s work on a system to track positive developments in your music-making, to help you notice when things are going well.

All of this information can be equally relevant to students and teachers. Communication about mental health is a two-way street, and it’s also more than that. In the end, it is our collective responsibility to create a culture that allows for different paces, different paths, and different goals. The pressure to conform to a one-size-fits-all mold for music education can add to the burden of depression and countless other mental health conditions and life situations.

Let’s start now—by talking about it!

[accordion]

[toggle title=”References” state=”opened”]

Ackermann, B. J., Kenny, D. T., O’Brien, I., Driscoll, T. R. (2014). Sound practice-improving occupational health and safety for professional orchestral musicians in Australia. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(September), 973. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00973

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Depressive disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm04

Cosci, F., & Chouinard, G. (2019). Chapter 7—The Monoamine Hypothesis of Depression Revisited : Could It Mechanistically Novel Antidepressant Strategies? In J. Quevedo, A. F. Carvalho, & C. A. Zarate (Éds.), Neurobiology of Depression (p. 63‑73). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813333-0.00007-X

Government of Canada. (2009, February 9). Mental Health—Depression [Education and awareness]. Aem. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/healthy-living/your-health/diseases/mental-health-depression.html

Maletic, V., Robinson, M., Oakes, T., Iyengar, S., Ball, S. G., & Russell, J. (2007). Neurobiology of depression : An integrated view of key findings. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 61(12), 2030‑2040. PubMed. DOI:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01602.x

Singh, M. K., & Gotlib, I. H. (2014). The neuroscience of depression : Implications for assessment and intervention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 62, 60‑73. PubMed. DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2014.08.008

Vaag, J., Bjorngaard, J. H., & Bjerkeset, O. (2016). Symptoms of anxiety and depression among Norwegian musicians compared to the general workforce. Psychology of Music, 44(2), 234‑248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735614564910

Voltmer, E., Zander, M., Fischer, J. E., Kudielka, B. M., Richter, B., Spahn, C. (2012). Physical and mental health of different types of orchestra musicians compared to other professions. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 27(1), 9.

Watson, A. H. D. (2009). “The Structure and Organization of the Brain.” In The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury (pp. 213–231). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=467511

Wristen, B. G. (2013). Depression and Anxiety in University Music Students. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 31(2), 20‑27.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Leave a Reply