Have you ever had any musician friends that appear to change with the seasons? Perhaps they are some of the happiest people you know during the summer but appear to be sad and irritable in the winter. Maybe they begin to attend classes and rehearsals less, or maybe their playing starts to sound a bit different. Have you ever wondered why this is the case?

Figure 1. Depressed

Recent studies have (unfortunately) shown that there are high levels of anxiety and depression in music students specifically (Igreja, 2023), because of music being such a highly-competitive professional field (Wristen, 2013). Competitiveness has been found to begin in childhood or early adulthood, and only worsens as music students transition into professionals (Wristen, 2013). University music students additionally face problems such as “living alone for the first time, learning time management and independent living skills, balancing the demands of jobs and school, living up to parental expectations, peer pressure, and concerns about gaining employment after graduation” which only worsen symptoms of anxiety and depression (Wristen, 2013). Music professor and researcher, Brenda Wristen, argues that with the high number of students affected by various mental health disorders, “educating students about mental health issues and where to seek treatment is a vital part of advancing comprehensive health for musicians” (Wristen, 2013).

While there are many different mental health conditions that should be discussed, this blog post will focus specifically on Seasonal Affective Disorder– a mood disorder that is often overlooked and under-researched.

There is a “continuing need to promote awareness of indicators and potential impacts of depression and anxiety among music students and to increase cultural acceptability of seeking treatment for these conditions” (Wristen, 2023, p. 25)

What is Seasonal Affective Disorder?

Seasonal affective disorder, commonly referred to as SAD, is defined by professionals as “a combination of biologic and mood disturbances with a seasonal pattern, typically occurring in the autumn and winter with remission in the spring or summer” (Kurlansik & Ibay, 2012). The age of onset is believed to be between the ages of 18-30, however people can develop SAD at any age (Melrose, 2015, p. 2). Considered a subtype of major depressive disorder, bipolar I, and bipolar II disorder, SAD causes people to experience recurring episodes of major depression, mania, and hypomania (Avery, 2022). Despite being considered a common mood disorder, especially in locations that have long, dark, and cold winter months, this disorder often goes undiagnosed (Zauderer & Ganzer, 2015).

“Seasonal Affective Disorder is still a somewhat mystery to researchers” (Götz, 2015, p. 24).

Did you know that SAD is seen more commonly in women than men? Researchers believe there is a 4:1 ratio within the “childbearing years” (Kurlansik, 2012, p. 1037), which is a number significantly larger than the ratio seen in major depressive disorder, where women are only twice as likely as men to develop symptoms of depression (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2019). People who suffer from SAD, or experience symptoms related to SAD, are believed to be more sensitive to natural light, or the lack thereof. A change in the amount of natural light that one is exposed to can lead to symptoms of major depression due to changes in their circadian rhythms. You may be asking yourself…

How can a lack of sunlight lead to symptoms of major depression? Why are so many people undiagnosed? What are circadian rhythms?

Let’s start with some definitions of terms that will be used throughout this post:

Table 1. Important Terms and Definitions

| Term | Definition |

| Major Depressive Disorder | A mood disorder that affects the way a person feels, thinks, and behaves, often leading to persistent feelings of sadness or emptiness (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2022). Hypomanic and manic episodes must not be present, however some symptoms may align (APA, 2022) |

| Mania | A condition in which a person experiences extreme and unusual elevated changes in mood and energy levels (Cleveland Clinic Staff, 2021). |

| Hypomania | A form of mania that often lasts for a shorter period and is considered milder (Mind, 2023) |

| Bipolar I Disorder | A mental health condition that causes manic episode(s) and hypomanic or major depressive episodes (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2022, Bipolar Disorder). |

| Bipolar II Disorder | A mental health condition that causes both major depressive and hypomanic episodes but not manic episodes (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2022, Bipolar Disorder). |

| Winter-pattern SAD | Symptoms of SAD typically present themselves in the fall or winter months, going into remission in the spring or summer. This is the most common form of SAD (Melrose, 2015, p. 1). |

| Summer-pattern SAD | Symptoms of SAD typically present themselves in the spring or summer, going into remission in the fall or winter. There is less known about this form of SAD (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023, What Causes SAD section). |

| Circadian rhythms | A natural cycle that occurs every 24-hours and causes physical, mental, and behavioural changes. Rhythms are typically synchronized to the rising and setting of the sun. (National Institute Health and Human Services, 2023). |

What causes SAD?

SAD is a mental health disorder that would most closely be related to the nervous system, but more specifically, the brain. If you are unfamiliar with (or need a refresher on) the nervous system, please watch the 2-minute video below summarizing the two major divisions of the nervous system.

“There may be several biologic mechanisms underlying SAD, including circadian phase delay or the phase shift hypothesis. Additional contributing mechanisms may include retinal sensitivity to light, neurotransmitter dysfunction, genetic variations affecting circadian rhythms, and serotonin levels” (Kurlansik & Ibay, 2012, p. 1037).

Research has shown that people with SAD have altered levels of melatonin and serotonin, both of which help to maintain the body’s natural rhythms. Changes in levels of melatonin and serotonin will disrupt the body’s rhythms and can lead to changes in sleep, mood, and behaviour. A lack of sunlight will lead to increased levels of melatonin and decreased levels of serotonin (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

Melatonin: A hormone that regulates the sleep-wake cycle (Cleveland Clinic Staff, 2022).

Serotonin: An important neurotransmitter and neuromodulator that is part of the central nervous system. It affects mood, cognition, movement, arousal, and autonomic function (Brindley et al., 2017, p. 943).

Spoiler alert! A decrease in serotonin and an increase in melatonin (during non-sleeping hours) is not good. Keep reading to find out why…

I don’t get it… why can a change in the production of melatonin and serotonin lead to SAD?

There are two main theories that explain why this occurs:

1. Phase Shift Hypothesis

The Phase Shift Hypothesis refers to a shift in the circadian clock that typically begins when there is a change in the amount of daylight. Upon waking up, people with regular circadian rhythms experience an increase in body temperature, as well as higher levels of concentration and alertness. When it nears the end of the day, they will begin to experience a decrease in body temperature, as well as lower concentration and energy levels. Lower energy levels are caused by an increased amount of melatonin, which as explained before, is stimulated by darkness. Exposure to natural light will have an opposite effect; reducing the amount of melatonin produced leading to higher energy levels (Götz, 2019, p. 24). The phase shift hypothesis applies when one’s circadian rhythm shifts and no longer follows the expected 24-hour cycle.

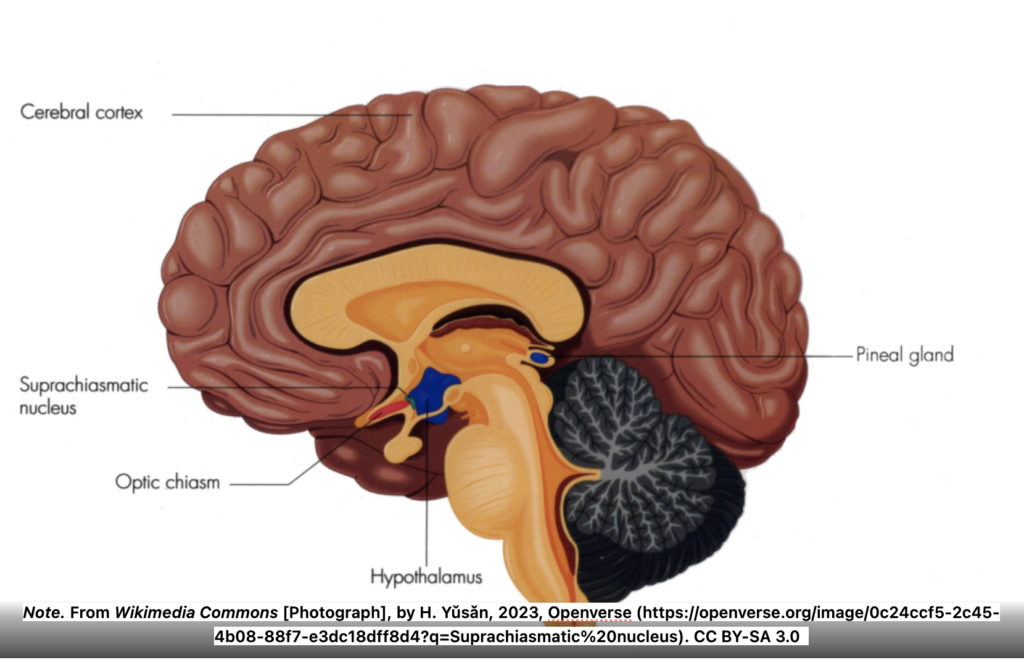

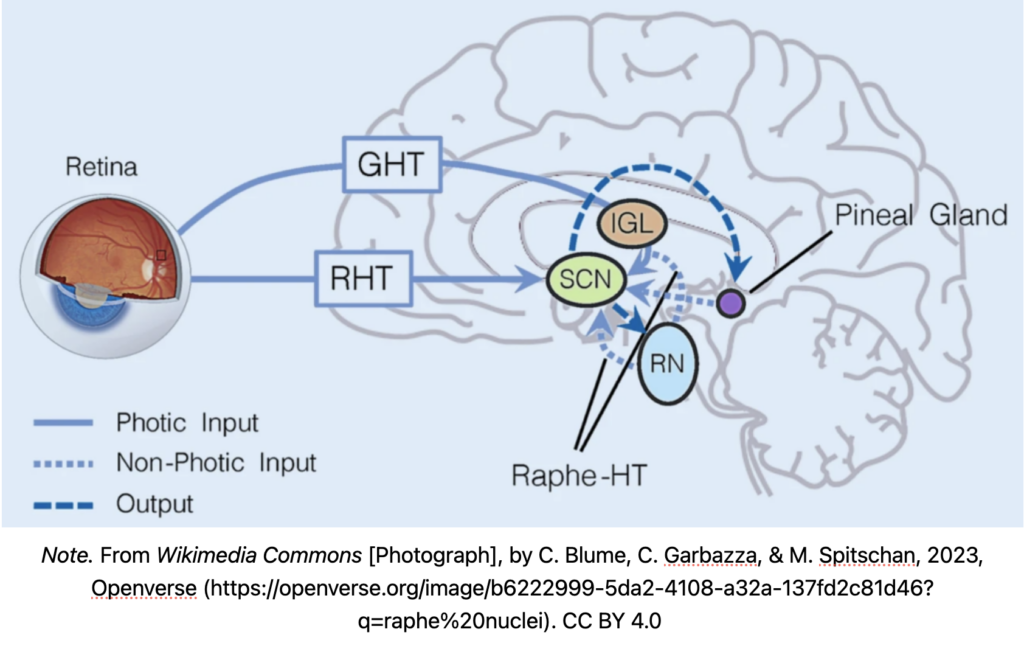

The main regulator for circadian rhythms is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the anterior hypothalamus in the brain and seen in Figure 2 below. Disruptions to the SCN have been connected to mood and sleep disorders, which often result in negative mood and behavioural changes, and can lead to symptoms of SAD (Ma & Morrison, 2023).

Figure 2. Suprachiasmatic nucleus

2. Serotonin Hypothesis

Serotonin is an important neurotransmitter that is directly regulated by natural light. When light hits the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), a signal is transmitted to the SCN. The SCN is connected to another part of the brain called the raphe nuclei, which is the “origin of all serotonin neurons in the brain” (Götz, 2019, p. 24), and can be seen in Figure 3 below. When people experience reduced exposure to natural light, the raphe nuclei becomes less active, and the production of serotonin decreases. As Götz (2019) explains, less sunlight can cause a “deficiency of central serotonergic transmission” often leading to symptoms of depression (p. 25).

Neurotransmitter: A “chemical messenger” that carries signals throughout the body, allowing the body to move, feel, and function properly (Cleveland Clinic Staff, 2022).

Retinal Ganglion Cells: The “bridging neurons that connect the retinal input to the visual processing centres within the central nervous system” (Kim et al., 2021).

Figure 3. Input and output pathways of the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN)

- GHT = geniculohypothalamic tract

- RHT = retinohypothalamic tract

- IGL = intergeniculate leaflet

- SCN = suprachiasmatic nuclei

- RN = raphe nuclei

- Raphe-HT = raphehypothalamic tract

What are the effects of SAD on the mind?

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (2023), common symptoms are:

Figure 4. Sad

- Sad, anxious, “empty” mood for most of the day, almost every day, for a minimum of 2 weeks

- Hopelessness, pessimism, worthlessness, helplessness

- Irritability

- Frustration

- Restlessness

- Feelings of guilt

- Feeling unmotivated

- Loss of interest and pleasure in hobbies

- Difficulty remembering, concentrating, and making decisions

- Social withdrawal

- Thoughts of death

Fun Fact! Mood, focus, well-being, and social support have been found to be “positively correlated with each other” (Chester et al., 2024). This means that if a person is experiencing symptoms of SAD related to mood and general mental well-being, it is likely that other areas of their life, such as focus or social support, will be affected too. Researchers have also found that negative moods can lead to decreased levels of motivation (Cawley et al., 2013). Neat! Remember that all areas of well-being can impact one another, and each area should be considered when assessing your overall health.

How can the mental effects of SAD affect musicians specifically?

While there has been no research done on the effects of SAD on musicians specifically, I can easily see how the symptoms listed above could affect the life of a musician, from my own experiences as a vocal student. Suffering from SAD could cause musicians to experience:

- A loss of interest and pleasure in playing instruments or singing

- Difficulty finding motivation to practice or participate in classes

- Difficulties focusing in lessons, practice sessions, performances, and classes

- Difficulties memorizing repertoire and remembering lesson notes

- Social withdrawal

- Difficulty networking or collaborating in group environments

- Missing class or lessons

- Frustration → can create a negative headspace while playing that leads to ineffective and unproductive practicing

What are the effects of SAD on the body?

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (2023), common physical symptoms are:

Figure 5. Personal injury back pain

- Physical aches and pains

- Headaches

- Cramps

- Digestive problems

- Sleeping problems

- Fatigue and lower levels of energy

- Weight loss or weight gain

The symptoms of seasonal affective disorder are often consistent with other forms of depression; however, some symptoms are specific to SAD, and will differ between winter-pattern SAD and summer-pattern SAD (Kurlansik & Ibay, 2012, p. 1037).

The following lists consist of symptoms that are specific to SAD.

Winter-pattern (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023, What are the Signs and Symptoms of SAD section).

- Oversleeping

- Overeating

- Carbohydrate craving

- Hyperphagia → extreme hunger often leading to weight gain

Summer-pattern (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023, What are the Signs and Symptoms of SAD section).

- Difficulties sleeping

- Lack of appetite

- Restlessness

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Violent/ aggressive behaviour

How can the physical effects of SAD affect musicians specifically?

- Problems with posture and/or holding an instrument correctly due to body aches and pains

- Problems with breath control and endurance due to weight gain (Gupta, n.d.)

- Insufficient sleep can:

- Affect concentration, leading to “decreased accuracy and effectiveness of work performance” or music performance (Orzel-Gryglewska, 2010)

- Reduce lung function making it difficult for musicians to take and sustain the appropriate amount of air (Hamdan et al., 2018, p. 85)

- Affect both performance accuracy and speed and can have a negative impact on the fine motor skills involved in playing an instrument (Simmons & Duke, 2006).

- Affect protein synthesis, a process in which cells “repair damaged muscle fibers and [build] new tissues” (Rocha & Behlau, 2017, p. 8). This will lead to protein degradation and eventually the loss of muscle mass and the thinning of the vocal folds.

- Lead to decreased muscle tension, a more monotonic or “flat” sound in the voice, reduced pitch variations, and less vocal intensity leading to a softer sound (Icht et al., 2020).

- Problems performing, practicing, and attending classes due to an increase in anxiety

- Anxiety can cause muscle tension in the voice box leading to a lack of vocal control and a breathy sound quality (Plocienniczak & Tracy, 2022).

- Physical symptoms of anxiety include an increased heart rate, nausea, rapid and shallow breathing, and difficulties concentrating and remembering all of which can make performing and remembering repertoire difficult (Watson, 2009).

How is SAD Diagnosed?

According to the current DSM-V, SAD is identified as Major Depressive Disorder with a seasonal pattern, rather than being considered its own distinct disorder (Overland et al., 2020, p. 2). This has made the diagnosis criteria slightly unclear, and it is difficult to find information on the number of symptoms required to receive an official diagnosis. The current criteria are as follows:

- Symptoms of major depressive disorder and/or symptoms related specifically to SAD.

- Minimum of two major depressive episodes and periods of remission occurring during specific seasons for at least two consecutive years (APA, 2022).

- Seasonal depressive episodes must be more frequent than nonseasonal depressive episodes (APA, 2022).

“A high percentage of patients with depression who seek treatment in a primary care setting report only physical symptoms, which can make depression very difficult to diagnose” (Trivedi, 2004).

The current screening methods vary from one place to another, but can include a seasonal pattern questionnaire (Melrose, 2015, p. 2) and standard depression evaluation measures, such as clinical interviews, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and psychological evaluations (Kurlansik & Ibay, 2012, p. 1038). Medical professionals may also choose to complete a physical exam and lab tests to ensure that symptoms are not being caused by an underlying physical health condition (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2021).

Research has shown that people with SAD do not always experience symptoms every year, meaning that the current criteria may prevent people from receiving the proper diagnosis and treatment methods (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023). In terms of diagnosing SAD, many of the current methods involve self-reporting, which researchers argue are not always accurate or reliable (Kenny & Ackermann, 2015). Inaccuracies in self-reporting measures can lead to people receiving an improper diagnosis or no diagnosis at all. Should more research be done on other, more reliable measures for diagnosing SAD? Should medical professionals rework the current criteria?

“[Self-reporting] measures are unable to differentiate those who are genuinely psychologically healthy from those who maintain “a facade or illusion of mental health based on denial and self-deception,” or who somatize their psychological distress” (Kenny & Ackermann, 2015, p. 55)

Treatments

For a brief introduction to the current treatments used to treat SAD, please watch the short 2-minute video below.

ChristianaCare. (2020, January 3). What are the treatments for seasonal affective disorder? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3A8Rhr2yT58

Let’s dive a bit deeper into these ideas. As you saw in the video, treating SAD typically involves the use of four main methods:

1. Light therapy

- Exposure to a bright light box, as shown in Figure 6 below, for 30-45 minutes per day first thing in the morning (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

- Light is around 20 times brighter than indoor light and is made to filter out harmful UV rays (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

- Side effects include: agitation, anxiety, eye strain, fatigue headaches, insomnia, irritability, nausea

- One researcher found that light therapy “may be associated with a switch to hypomania or mania in vulnerable bipolar patients” (Golden et al., 2005).

Figure 6. Light therapy lamp

2. Psychotherapy

- A form of counselling that aims to help patients change their habits, behaviours, and ways of thinking (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the most common form of psychotherapy and has been adapted for SAD specifically (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

- Discussion is focused on negative thoughts surrounding seasons and seasonal changes

- Participants are encouraged to identify and participate in indoor and outdoor activities that they enjoy

- Counselling will typically involve 2 weekly group sessions over 6 weeks (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

- Believed to be equally as effective as light therapy, however, counselling may have a longer lasting impact (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023).

3. Antidepressant medication

- Prescription medication that changes the brain’s production and/or use of chemicals (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023)

- Often take 4-8 weeks to begin working, and symptoms related to sleep, appetite, and concentration typically improve before mood (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023)

- All medications can have side effects

- Ex. decreased alertness, headaches, nausea, suicidal feelings (Mind, 2020).

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) help to increase serotonin activity and is the most common type of antidepressant medication (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023)

4. Vitamin D supplements

- Supplements can be prescribed or sold over the counter, and may come in different forms including capsules, tablets, gel capsules, gummies, and liquid drops

- Low levels of natural sunlight lead to low levels of vitamin D in the body

- Low levels of vitamin D are often correlated with increased rates of depression (Melrose, 2015)

- Researchers have found that this occurs more commonly in females than males (Covassin et al., 2019).

- Some researchers argue that supplements have no effect while others argue that they are equally as effective as light therapy (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023)

Light therapy and vitamin D supplements are typically recommended for those suffering from winter-pattern SAD, whereas psychotherapy and antidepressant medications are used for treating symptoms of depression in general (National Institute of Mental Health, 2023). There are unfortunately no specific treatment methods for summer-pattern SAD, but medical professionals recommend that people limit natural light exposure and stay cool in the summer, especially when sleeping (Avery, 2022). Aside from the last bullet point below, which is applicable to only winter-pattern SAD, some additional suggestions for both patterns include:

- Hormonal therapy (Muni & Abbas, 2024)

- Dietary modifications (Muni & Abbas, 2024)

- Exercise (Muni & Abbas, 2024)

- Meditation (Muni & Abbas, 2024)

- Proper sleep (Muni & Abbas, 2024)

- Dawn stimulation

- A device typically used in the morning that emits low levels of light gradually increasing over a “period of 30-90 minutes” (Avery, 2022).

- This is a form of light therapy that is less intense than a bright light box (Avery, 2022).

Now that we know what SAD is and how it affects musicians, what can be done moving forward? What can music programs do to help support their students who are struggling with SAD?

Learning about SAD has allowed me to come up with some of my own suggestions of ways that music students can be further supported. I encourage music institutions to consider the following:

Figure 7. Coddington’s animal phys student in the sun

- Offer some light therapy boxes in practice rooms or common spaces in music buildings (Covassin et al., 2019).

- Hold classes in rooms with lots of windows and access to natural light

- Create regular and mandatory training programs on mental health conditions to make staff and students aware of common symptoms, treatment methods, and available resources → Can be done through an online module

- Hold classes outside when possible (as demonstrated in Figure 7)

- Consider student and faculty input when determining the scheduling of classes → Ex. Blocking classes in mornings or evenings will prevent students from being kept inside during the limited hours of daylight in the winter

- Install air conditioning units in music buildings to keep students cool in the warmer months

- Design future music buildings to have more windows and access to natural light

- Practice rooms should be both above ground and in the basement, to ensure that needs are met for both those who require or are limiting natural light exposure

- Create wellness programs and support groups for students and faculty

- Free nutritious snacks

- Light physical activity sessions → yoga, stretching, Zumba lessons, dance lessons, aerobic exercises

- Fun Fact: Studies have shown that mood typically improves within 1-8 weeks after beginning regular aerobic exercises (Drew et al., 2021). How neat is that?

- Stress management workshops

- Breathing and full body warmup workshops (Applied Performance Sciences Hub [APSH], n.d.)

- Full body warmups “before practicing can prevent injury and pain, help with concentration and sustain energy levels throughout the day” (APSH, n.d.).

- Can provide students with techniques they can use on their own outside of the workshop

- Jam sessions (APHS, n.d.)

- Encourages performance and collaboration in a stress-free, relaxed, and encouraging environment

Fun Fact! The Applied Performance Sciences Hub at McGill University organizes many different wellness workshops and activities for staff and students throughout the school year. If you are interested in reading more about programs that could be implemented in your school, or if you attend McGill University and would like to participate in upcoming events, please click here.

It is important to note that while music programs and faculty can offer support, it is also the students’ responsibility to be mindful of their own well-being, and take the actions required to better their health.

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization, n.d.).

So, what can YOU do to take care of yourself?

While there are always exceptions, living a fulfilled life with disabilities or illnesses is completely possible when dealt with accordingly. As discussed previously, there are many different areas of health that each have an impact on one another and can affect one’s overall well-being. Despite receiving effective SAD treatments, a person may not feel healthy or at their best if they are not prioritizing other areas of their health too. Here are some ways that YOU can stay healthy and increase your overall well-being:

- Get a sufficient amount of sleep

- Average adult requires at least seven hours of sleep to function properly (Pacheco & Vyas, 2023)

- Limit screen time before bed

- Try to follow a regular sleeping schedule

- Use blackout curtains if necessary

- Eat well-balanced and nutritious meals

- Limit salt, sugars, and unhealthy fats (Tsai, 2024)

- Diet should include vitamins, minerals, fiber, whole grains, proteins, low fat dairy, fruits, and vegetables (Tsai, 2024)

- Stay hydrated

- Limit caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, and use of non-prescribed drugs

- Get plenty of exercise and fresh air

- Reduce sitting and screen time (Tsai, 2024)

- Sitting for long periods of time has “been linked to an increased chance of heart disease, weight gain, and early death” (Tsai, 2024)

- Make an effort to socialize with others

- Find enjoyable activities and hobbies

Conclusion

It is important to note that while there is a fair amount known on seasonal affective disorder currently, there is also a lot of research that can be done. Can there be specific treatments developed to treat summer-pattern SAD? Are there more reliable measures for diagnosing SAD? How can the current criteria be reworked to ensure more people get a proper diagnosis? Are there other ways that music students specifically are affected by this disorder?

Seasonal affective disorder can be difficult to live with, but it is not impossible to manage! If you are struggling with SAD, make sure to seek out and access the resources that are available to you and do not be afraid to advocate for changes in your institution’s music program. As Wristen (2013) states, “by teaching music students to identify and specifically address challenges inherent in the discipline, and helping them identify their own unique triggers for mental distress, music educators can contribute to overall student success and well-being at all levels of musical training” (p.26). Be sure to remember that individuals also hold a certain level of responsibility and while music programs and faculty can lend support, it is ultimately up to YOU to take control of your health. How are you going to start?

Author: Skylar Jordan

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Applied Performance Sciences Hub. (n.d.). Welcome to the LEAP campaign. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.appliedperformancesciences.org/leap-campaign

Avery, D. (2022). Seasonal affective disorder: Treatment. UpToDate. Retrieved March 14, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/seasonal-affective-disorder-treatment

Blume, C., Garbazza, C., & Spitschan, M. (2023). Input and output pathways of the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN). [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/b6222999-5da2-4108-a32a-137fd2c81d46?q=raphe%20nuclei

Brindley, R. L., Bauer, M. B., Blakely, R. D., & Currie, K. P. M. (2017). Serotonin and serotonin transporters in the adrenal medulla: A potential hub for modulation of the sympathetic stress response. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 8(5), 943-954. DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00026

Cawley, E. I., Park, S., Aan Het Rot, M., Sancton, K., Benkelfat, C., Young, S. N., …& Leyton, M. (2013). Dopamine and light: Dissecting effects on mood and motivational states in women with subsyndromal seasonal affective disorder. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 38(6), 388-397. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.120181

Chester, E. M., Kolacz, J., Ake, C. J., Thornburg, J., Chen, X., Shea, A. A., …& Vitzthum, V. J. (2024). Well-being in healthy Icelandic women varies with extreme seasonality in ambient light. International Journal of Psychology. DOI: 10.1002/ijop.13112

ChristianaCare. (2020, January 3). What are the treatments for seasonal affective disorder? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3A8Rhr2yT58

Cleveland Clinic Staff. (2021). Mania. Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21603-mania

Cleveland Clinic Staff. (2022). Melatonin. Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/23411-melatonin

Cleveland Clinic Staff. (2022). Neurotransmitters. Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22513-neurotransmitters

Covassin, T., Bretzin, A. C., Japinga, A., Teachnor-Hauk, D., & Nogle, S. (2019). Exploring the relationship between depression and seasonal affective disorder in incoming first year collegiate student-athletes. Athletic Training & Sports Health Care, 11(3), 124-130. https://doi.org/10.3928/19425864-20180710-01

Drew, E. M., Hanson, B. L., & Huo, K. (2021). Seasonal affective disorder and engagement in physical activities among adults in Alaska. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 80(1), 1-9. DOI: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1906058

Golden, R. N., Gaynes, B. N., Ekstrom R. D., Hamer, R. M., Jacobsen, F. M., Suppes, T., …Nemeroff, C. B. (2005). The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(4), 656-662. https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/epdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.656

Götz, J. (2019). Using human-centered design to treat winter depression. In: Seasonal Affective Disorder and Light Therapy. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from x

Gupta, R. (n.d.). The effects of weight on the voice. Osborne Head & Neck Institute. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.ohniww.org/effects-of-weight-gain-loss-voice-singing/

Hamdan, A., Sataloff, R., & Hawkshaw, M. J. (2018). Sleep, body fatigue, and voice. In: Laryngeal manifestations of systemic diseases. Plural Publishing, Incorporated. Retrieved October 24, 2023, from https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5676541

Icht, M., Zukerman, G., Hershkovich, S., Laor, T., Helped, Y., Fink, N., Fostick, L. (2020). The “Morning Voice”: The effect of 24 hours of sleep deprivation on vocal parameters of young adults. Journal of Voice, 34(3), 489.e1-489.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.11.010.

Igreja, A. B. M. (2023). Anxiety and depression in young musicians. [Doctoral dissertation, Clínica Universitária de Psiquiatria e Psicologia Médica]. MAIO https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/61683/1/AnaBIgreja.pdf

Kalfatermann. (2022). Light therapy lamp. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/6971ef90-2f8c-49b8-99d4-e056f49447aa?q=light%20therapy

Kenny, D. & Ackermann, B. (2015). Performance-related musculoskeletal pain, depression and music performance anxiety in professional orchestral musicians: A population study. Psychology of Music, 43(1), 43-60. DOI: 10.1177/0305735613493953

Kim, U. S., Mahroo, O. A., Mollon, J. D., & Yu-Wai-Man, P. (2021). Retinal ganglion cells- Diversity of cell types and clinical relevance. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2021.661938

Kurlansik, S. L., & Ibay, A. M. (2012). Seasonal affective disorder. American Academy of Family Physicians, 86(11), 1037-1041. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2012/1201/p1037.pdf

Ma, M. A. & Morrison, E. H. (2023). Neuroanatomy, nucleus suprachiasmatic. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 10, 2024, from

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022). Bipolar disorder. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bipolar-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355955#:~:text=Bipolar%20II%20disorder%20is%20not,which%20can%20cause%20significant%20impairment.

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2019). Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/depression/art-20047725#:~:text=About%20twice%20as%20many%20women,can%20occur%20at%20any%20age.

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022). Depression (major depressive disorder). Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20356007

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2021). Seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/seasonal-affective-disorder/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20364722

Marangell, L. B. (2004). The importance of subsyndromal symptoms in bipolar disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 65, 24–27. https://www.psychiatrist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/14070_importance-subsyndromal-symptoms-bipolar-disorder.pdf

Melrose, S. (2015). Seasonal affective disorder: An overview of assessment and treatment approaches. Depression Research and Treatment, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564

Mind. (2020). Antidepressants [Brochure]. Stirling, Scotland. https://www.mind.org.uk/media/6474/antidepressants-2020.pdf

Mind. (2023). Hypomania and Mania. Mind. https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/hypomania-and-mania/about-hypomania-and-mania/#:~:text=Hypomania%20and%20mania%20are%20periods,is%20a%20more%20severe%20form.

Muni, S. & Abbas, M. (2023). Seasonal depressive disorder. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 10, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568745/#article-126883.s7

National Institute of General Medical Sciences. (2023). Circadian rhythms. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/fact-sheets/Pages/circadian-rhythms.aspx#:~:text=Circadian%20rhythms%20are%20the%20physical,and%20temperature%20also%20affect%20them

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Seasonal affective disorder [Brochure]. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/publications/seasonal-affective-disorder/seasonal-affective-disorder-508.pdf

Neuroscientifically Challenged. (2014, August 8). 2-Minute neuroscience: Divisions of the nervous system [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3OITaAZLNc

Orzeł-Gryglewska, J. (2010). Consequences of sleep deprivation. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 23(1), 95-114. DOI 10.2478/v10001-010-0004-9

Overland, S., Woicik, W., Sikora, L., Whittaker, K., Heli, H., Skjelkåle, F. S., Sivertsen, B., & Colman, I. (2020). Seasonality and symptoms of depression: A systematic review of the literature. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 29, e31, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S2045796019000209

Pacheco, D, & Vyas, N. (2023, September 20). Frequently asked questions about sleep. Sleep foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-faqs

Rocha, B. R. & Behlau, M. (2018). The influence of sleep disorders on voice quality. Journal of Voice: Official Journal of the Voice Foundation, 32(6), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.08.009

SanDiego PersonalInjuryAttorney. (2015). Personal injury back pain. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/34adafaf-ee5d-4ad5-807c-6b39c520a76c?q=back%20pain

Schwegler, A. (2007). Sad. [Photograph]. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/4cQv4S

Simmons, A. L. & Duke, R. A. (2006). Effects of sleep on performance of a keyboard melody. Journal of Research in Music Education, 54(3), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.2307/4151346

Trivedi, M. H. (2004). The link between depression and physical symptoms. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(Suppl 1), 12-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16001092/

Tsai, A. (2024, March 6). 12 tips for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Healthline. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.healthline.com/health/how-to-maintain-a-healthy-lifestyle#maintain-a-healthy-weight

Van der Wel, S. (2010). Depressed. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/dfb620a2-6ec6-49f1-ad6e-d27d71eb5256?q=depression

Watson, Alan H. D. (2009). Performance-related stress and its management. In: The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury. Scarecrow Press. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

Willamette Biology. (2013) Coddington’s animal phys student in the sun. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/19f9e8d7-5816-4846-8ccc-2544f2595800?q=student%20in%20sun

Wristen, B. G. (2013). Depression and anxiety in university music students. Sage Journals, 31(2), 20-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123312473613

Yǔsǎn, H. (2023). Suprachiasmatic nucleus. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/0c24ccf5-2c45-4b08-88f7-e3dc18dff8d4?q=Suprachiasmatic%20nucleus

Zauderer, C. & Ganzer, A. (2015). Seasonal affective disorder: An overview. Mental Health Practice, 18(9), 21-24. DOI: 10.7748/mhp.18.9.21.e973