So, how can we utilize our brains to practice more effectively? We as musicians and music students must ask ourselves this question. As time goes on and we continue to learn about the brain, we’ve learned that not every traditional practice method and tool is as effective as we once thought. So, just as the scientific fields change and adapt to new knowledge, we as musicians must as well. This article is written with the purpose of evoking a critical lens on how we practice, and how understanding the neurochemical dopamine may improve our practice sessions.

“Rat embryonic nerve cells” by National Institutes of Health (NIH) is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

What are rewards?

Okay, we all can probably think of some rewards when prompted. Money, gifts, food, vacations, etc., but what are rewards to our brains? What do they do for us? How can we use rewards to help our practice become more efficient? “Rewards are any objects, events, situations or activities that attain positive motivational properties from internal brain processes.”(Hidi. S. 2016) It doesn’t have to be related to the task, but is clearly a response to a task. That sounds very simple, but the neurochemicals involved are very fascinating and knowing about dopamine especially can help us improve our practice and performance habits. To better understand rewards, we should take a look into our brains and talk a bit about dopamine.

Dopamine

This is the core of this blog. If you understand what dopamine does and how you can use it to help you practice and build habits, you’ve got everything you need from this article. So, what is dopamine? You might’ve heard of “dopamine hits” or “dopamine releases.” These terms have been popularized recently when people are talking about experiencing joy or happiness. BUT, I’m here to inform you that dopamine is not what makes you feel good or happy. Dopamine is what keeps us motivated. What does that mean? Well, dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is released in our brains between our nerve cells. The neurotransmitter dopamine is both an inhibitor and exciter, meaning that it can block or allow specific chemical information to be transferred from cell to cell during the action potential of a neuron. Dopamine is released as part of the body’s reaction to stress, but is also released after a form of positive reinforcement, I.e. receiving a reward. (Fink, G. 2019)

Dopamine is not the reward, it is what causes you to chase the reward. It’s what motivates you to take action. This is a very significant difference. You don’t need dopamine to enjoy something like ice cream, but you do need dopamine to work a job so you can buy ice cream and enjoy it. Dopamine is largely responsible for what drives us to repeat a habit. We are constantly building and reinforcing habits when we practice our instruments. Something is motivating us to continue these habits, and that something is dopamine. This helps us understand how our habits, both good and bad, form.

Some important information is best depicted with an example of a Pavlovian response. When someone is learning a Pavlovian behavior with a cue and reward, in the early stages of this process dopamine is released after the reward. But, interestingly, as time continues, that dopamine release after the reward actually decays and loses potency, but there is a new rise in dopamine levels after the cue. (Lefner, etc., 2022) When applying this to practice, we must realize that when learning a new piece, skill, and/or habit, we can give ourselves rewards after successful sessions. Then over time, the dopamine that we get from that reward will shift from the reward to the behavior, meaning that we will be more motivated to do the new skill or habit correctly.

Myelin and Encoding

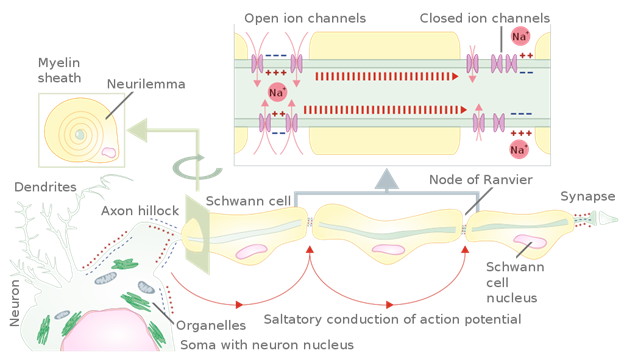

If you’ve done some research into learning or have taken a course about efficient practice, you’ve probably already learned about myelin and myelination. To the uninitiated, here’s a crash course. As our brain develops and we learn or encode new information, our brains organize neural pathways. These pathways are made of nerve cells or neurons, which will bundle into fibers which will go all over the body to form the nervous system. Neurons in the brain communicate to one another through electrical signals that release chemicals giving specific information. As a pathway is used more and more, the brain will adapt to make that pathway more efficient. The neurons will form myelin sheaths around their tails or axons. Myelin is the white matter of the brain. These sheaths allow the electrical signals to be sent much faster, improving the pathway. This process is known as myelination.(Girault, J. B. 2018) Think of it like internet speeds: myelination takes your basic internet plan to something high speed like google fiber. Myelinated paths are more consistent and more efficient, and all of our practice and encoding is to make these high speed paths in our brains.

There it is, now go practice! Well… maybe not yet. So, we now know about the white matter in our brain. We know that when we repeat something we’re preparing neural pathways for myelination. We know that myelinated pathways are much faster than pathways without myelination. But what does that encoding process have to do with dopamine?

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Dopamine and Practice”]

We’ve talked about dopamine, and we’ve reminded ourselves how we encode information through myelination. But what can we change in our practice to take advantage of this knowledge? Now understand, we’ve always been releasing dopamine and encoding information, nothing new is happening to us. But, with a better understanding of the mechanics of these neurochemicals and processes, we can practice more effectively and efficiently. If you know more rules about a game, you’ll hopefully be better at playing it.

So to review, dopamine is our motivation for rewards, and myelin gets wrapped around our axons to help us repeat actions more efficiently and accurately. So here’s the basic idea, we reward ourselves deliberately for good habits and successful actions so that we can more effectively myelinate the correct pathways. We reward ourselves for doing the right things so we learn faster. Rewards are only given out for doing a good job.

It’s basic, it’s simple, and it makes a lot of sense. If we do something well, we should reward ourselves for that success. But, how many of us only focus on our mistakes, or practice not to fail? How many of us constantly judge ourselves for our deficiencies as players? When was the last time you practiced something and counted all the things that went well?

This is why I wanted to write about this topic. A lot of us musicians and music students need to change our perspective a bit. Recognizing and understanding mistakes are very important to our progress. Most mistakes are caused by some kind of misunderstanding of a situation. You didn’t hear an interval correctly, the rhythm was different than what you thought, you didn’t have the right posture or technique to play as well as you could’ve, etc. Understanding and acknowledging mistakes is important for learning, but there’s a flip side to it. We need to celebrate our successes, and reward good behaviors.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”What is a Reward? (Revisited)”]

So we understand that rewarding good behaviors and successes is important for our progress. So does that mean we go and get our favorite junk food after every practice session. Not exactly. Not all rewards are things that are bad for you like junk food “Rewards are any objects, events, situations or activities that attain positive motivational properties from internal brain processes.”(Hidi. S. 2016) A reward can be taking a relaxing walk outside, listening to music you really enjoy, reading, watching your favorite movie. A reward can be day dreaming, going to the gym, making plans with friends, taking a nap, drawing, playing video games, and so on. Just keep in mind, the rewards we pick should probably be sustainable for our health, and we can rotate rewards for ourselves. Maybe you get junk food once a week, and taking some walks and reading are what you do otherwise. Some self-destructive behaviors like drinking, using drugs, eating junk food, etc. are rewards, but they’re not sustainable over a long period of time.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Reward Systems”]

Maybe as important as the reward is some self discipline. Here’s an example of a poor design for a reward. You give yourself a practice goal, “I’m going to play measures 50 to 60 with accurate rhythm and intonation at 90bpm. Once I achieve that I’m going to reward myself by going on Instagram for 15 minutes.” In theory, this is a fine example of a reward system. But, what happens if I don’t achieve my goal? Instagram is really easy to just open, so what happens if I just go on it anyways? Do you see the issue that can arise in practice with a reward that’s as easy to access as an app? So, what could we change to make this better? Well, in this case we should probably pick a reward that’s more meaningful than scrolling on an app that’s really easy to access. Resisting something that’s very easy to access can be very challenging. That’s part of why social media is so addictive for some of us. Here’s a clip that explains social media and dopamine better.

Okay, so how frequently should we reward ourselves and what should the “size” of our rewards be? It’s an interesting question, but cannot be answered so easily unfortunately. Instead, we should focus on some things we’ve discussed so far. When first learning something or encoding, we are myelinating our neurons, and we receive our dopamine release after a reward initially. Over time, that dopamine release will be after the action or habit. With those things in mind, we should focus on deliberately rewarding good work in our practice especially at the beginning of our learning process. After successful repetition, when you really nail something in practice, I encourage you to take time and acknowledge that success with a genuine reward. Tell yourself you did a good job, write in a journal about how well it went, tell a friend how excited you are to be making progress. Find something genuine and reward yourself for your successful early work especially. That positive reinforcement should help you myelinate the right channels and train your body to repeat that success.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Intrinsic VS Extrinsic Motivation”]

Dopamine keeps us motivated to achieve a goal and get a reward. I’ve said this so many times in so many words. But, does our motivation always have to come from within ourselves? ALERT, THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION IS CONTROVERSIAL. Okay, what are intrinsic and extrinsic motivation? Basically, intrinsic motivation is motivation that comes from within ourselves. WE want to do something. Extrinsic motivation is motivation that comes to us from outside of ourselves. SOMEONE ELSE wants us to do something. (Hidi, S. 2016) An example: Sydney practices the flute because they want to improve as a musician so they can play music and express themselves. After school they still practice because they enjoy that mode of expression. They are intrinsically motivated. Oscar practices the flute because he was told by his teacher that to get a good grade he needs to play well in his lessons and Oscar wants to have good grades to get into his chosen university to study engineering. After getting into university Oscar drops the flute after one semester of playing in a school band that is not graded. Oscar was externally motivated. Both people were practicing the flute in school, but their motivation was completely different. Without the grades and pressure from the teacher, Oscar stopped playing the flute.

Classically speaking, intrinsic motivation is a better form of motivation. It’s understandable why that is. Motivation from within ourselves keeps us going towards goals more reliably than external pressures and motivations. That’s not controversial, but here’s something that is. Think back to Oscar and Sydney. Yes, Sydney wanted to practice for themselves, but Oscar practiced too even if he wouldn’t have without the grade. Because the grade existed he did the same thing Sydney did. What I’m trying to get at is that although extrinsic motivation is frowned upon, it is still motivation, and it can still help us reinforce good habits.

Basically, the neuroscience community can argue that all rewards can benefit learning processes, but the removal of external rewards can slow down learning and motivation. (Hidi, S. 2016) Let’s go back to Oscar. He was externally motivated in school by his grades. Without that external reward in university, Oscar lost motivation to continue with the flute. As previously stated, if your motivation is not intrinsic, that’s not the worst thing. But, if your motivation is mostly external: winning a job, beating people in competitions, making as much money as possible, etc. If it’s external and you aren’t receiving those external rewards, you may experience a drop in motivation and your progress may slow down.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Are You Rewarding Bad Behaviors?”]

So unfortunately, as far as dopamine is concerned, “we are what we eat.” It’s important to only reward our practice habits when we achieve our goals. If you don’t execute what you set out to do in a practice session, you shouldn’t reward yourself. It’s helping your brain remember bad habits and failures as if they are good habits and successes. Your brain and body don’t exclusively program and myelinate when you play the opening of the Stravinsky well, they program what’s rewarded and repeated the most.(Girault, J. B. 2018) If you play something wrong 5 times in a row and nail it the sixth time, what’s your brain going to remember? Think about it this way: you played something wrong 5 times and only got it right once, your percentage on that is roughly 17%. You played it with mistakes 83% of the time. Unfortunately, your brain just rewarded itself after you started trying the same thing over and over again after the first wrong run through. That’s how you form a habit, and unfortunately in this scenario you’re forming a bad habit. So, after the first repetition, if there are mistakes, we need to address them and start forming good habits there before we can try to run it again. The first run through wasn’t necessarily the problem, running it over and over again the same way after making the mistake was. Basically, if you let a mistake slide or aren’t totally honest with yourself, you may be rewarding your bad habits. Run throughs without stopping and practicing performing are important, but when just practicing and learning we need to be honest with ourselves and address what we do not understand specifically.

[/toggle]

Closing Thoughts

Hopefully this article answered some questions and gave you some more things to explore. This is not an all inclusive on how to frame and improve your practice techniques. There are journals and magazines out there like The Bulletproof Musician or The Strad which can list specific techniques and methods to try to “hack” your practice. Another valuable source of information on the brain and practice is the work done by Molly Gebrian. This article was meant to highlight one aspect of practice which I felt was underrepresented at McGill University during my studies. Working in positive reinforcement and rewards into your practice. So many of us focus on the problems in our playing but ignore what we do well. Only acknowledging our strengths will not help us improve, but positive reinforcement when learning techniques and skills will help us improve our relationships with our weaknesses and deficiencies as musicians. Try to reward yourself especially when you improve your weaknesses. Acknowledge your progress. Be kind to yourself.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”References”]

Elliott, B. L. (2021). Motivated memory: Structural and functional neural correlates (Order No. 28647958). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2571958741). Retrieved from https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/motivated-memory-structural-functional-neural/docview/2571958741/se-2

Fink, G. (Ed.). (2019). Stress: physiology, biochemistry, and pathology : handbook of stress (Vol. Volume 3 /). Academic Press. Retrieved December 1, 2022, from INSERT-MISSING-URL.

Girault, J. B. (2018). Brain structural maturation and cognitive abilities in early life (Order No. 10786814). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2058812904). Retrieved from https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/brain-structural-maturation-cognitive-abilities/docview/2058812904/se-2

Hidi, S. (2016). Revisiting the role of rewards in motivation and learning: implications of neuroscientific research. Educational Psychology Review, 28(1), 61–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9307-5

Knowlton & Castel. (2022). Memory and reward-based learning: A value-directed remembering perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 73, 25-52. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032921-050951

Lefner, Stelly, Fonzi, Zurita, & Wanat, (2022). Critical periods when dopamine controls behavioral responding during Pavlovian learning. Psychopharmacology, 239, 2985-2996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-022-06182-w

Murphy, R. A., & Honey, R. C. (Eds.). (2016). The wiley handbook on the cognitive neuroscience of learning. Wiley Blackwell. Retrieved December 1, 2022, from INSERT-MISSING-URL.

Palminteri, S., Lebreton, M., Worbe, Y., Hartmann, A., Lehericy, S., Vidailhet, M., Grabli, D., & Pessiglione, M. (2011). Dopamine-Dependent Reinforcement of Motor Skill Learning: Evidence from Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome. Brain, 134(8), 2287–2301

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Media Credits”]

“flute player” by snapclusion is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/?ref=openverse.

Huberman, A. [Andrew Huberman]. (2021, August 16). Dr. Anna Lembke: Understanding & Treating Addiction | Huberman Lab Podcast #33 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/p3JLaF_4Tz8?t=421

Neuroscientifically Challenged. (2014, July 26). 2-Minute Neuroscience: Action Potential [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/W2hHt_PXe5o

“Propagation of action potential along myelinated nerve fiber en” by Helixitta is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/?ref=openverse.

“Rat embryonic nerve cells” by National Institutes of Health (NIH) is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/?ref=openverse.

[/toggle]