Has this ever happened to you? You are in a performance situation and you seem to forget everything you ever practiced. What if I told you there is a better way to learn efficiently and gain better retention of what you practice?

Let’s learn about Combined Practice.

Deliberate Practice

Before we get into Combined Practice, let’s review how most of us naturally learn to practice.

Deliberate Practice is a form of enhanced learning that is characterized by the following traits:

- Development of a skill that has a history with effective training strategies available to learn from.

- Development takes place outside of the comfort zone.

- The practice involves well-defined and specific goals.

- Learning requires full attention.

- Involves feedback and modifications in response to that feedback.

- Produces and depends on effective mental representations.

- Involves building upon or modifying previously learned skills.

(Ericson & Pool, 2016, pp. 99-100).

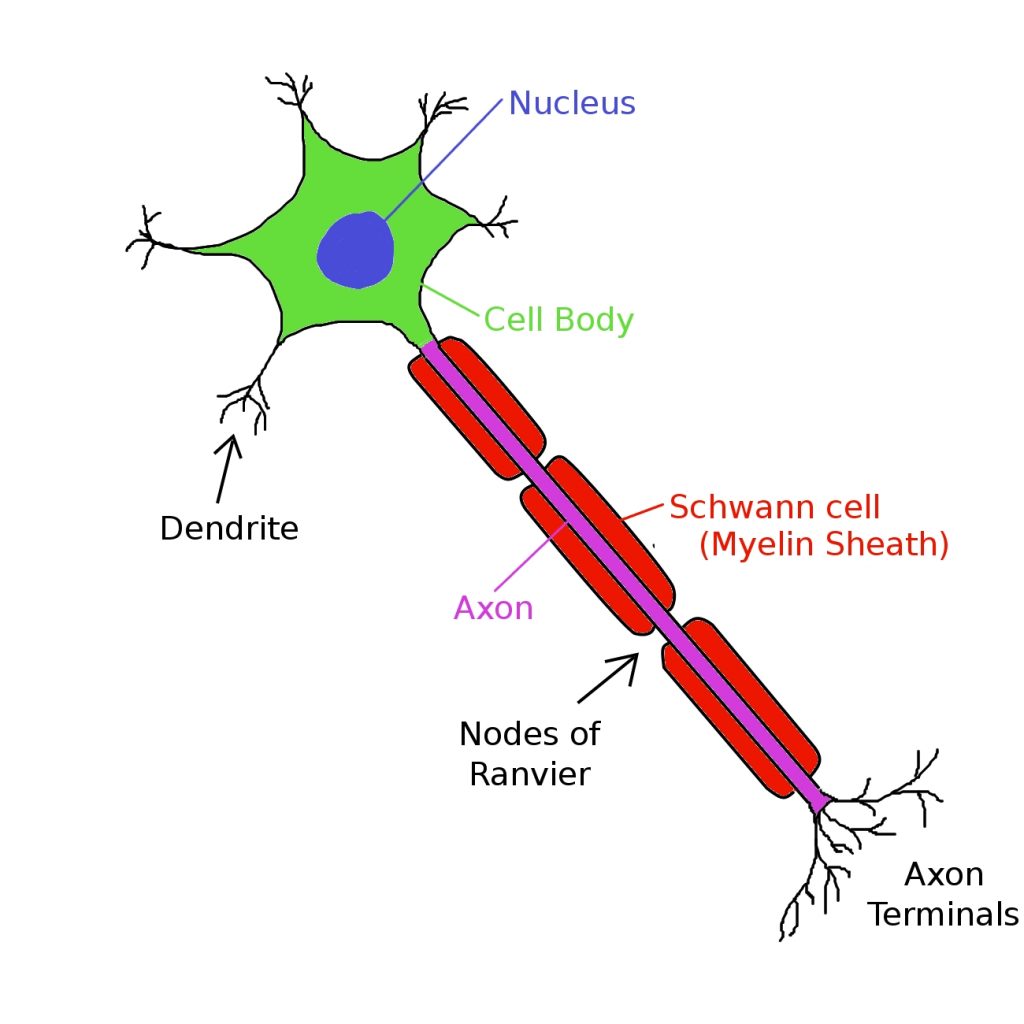

Most western classical musicians work with the characterizations of Deliberate Practice in their development, to varying degrees, and make advancements in their performance. How does it work? According to Ericcson (2016), “regular training leads to changes in the parts of the brain that are challenged by the training” (p. 45). Looking back at the list of Deliberate Practice requirements, learning must take place outside of the comfort zone, have specific goals, and must require full attention. When these three aspects are in effect, the brain can make changes and recall information better resulting in advanced learning. Changes in the brain are what is referred to as neuroplasticity or brain plasticity.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Neuroplasticity”]

Neuroplasticity is defined as “the general ability of our central nervous system to adapt throughout the life span to changing environmental conditions, body biomechanics, and new tasks. Brain plasticity is most typically observed for complex tasks with high behavioral relevance and those which activate circuits involved in emotion and motivation.” (Altenmüller & Furuya, 2017, p. A59). Based on this definition, the brain needs to be challenged for neuroplasticity to take place. Neuroplasticity leads to improvement in performance by changing the brain and strengthening positive connections in the brain!

[/toggle]

If I am making changes to my brain and learning deliberately, why can’t I remember what I practice on stage?

Spittle (2010) performed a test on the deliberate physical practice of throwing a dart and its effect on retention. According to the study, deliberate physical practice was shown to make immediate improvements in performance but was not as successful at enhancing retention. Since the study was presented on a skill the participants were not familiar with, having one deliberate practice session may not increase retention drastically. As you are an experienced musician who practices regularly, retention is built over time through repetitions, but there is a more effective and healthy way to learn!

What else can you do?

Use your brain!

Mental Practice

What is Mental Practice and how do I use it?

According to Steenstrup (2021), “[Mental practice] is commonly described as the ability to imagine the correct movements of task-relevant body parts performing their desired function and for musicians, this is very closely linked to simultaneously imagining the audible result of this activity” (p. 2). Based on Steenstrup’s definition, mental practice is the ability to recall previously learned physical and auditory information, and create an image of it in your head. While this may sound easy, it can be more difficult than you think. In order to imagine a specific musical idea, your mental image of the concept needs to be clear and focused and this can take some practice.

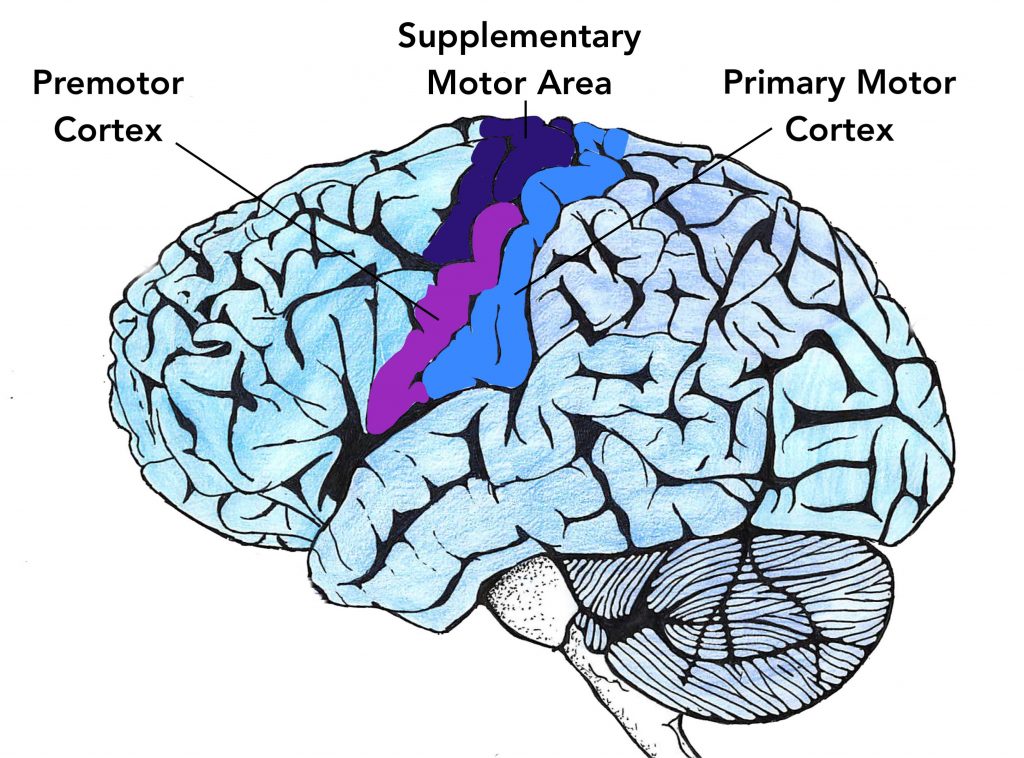

Violist and neuroscientist Molly Gebrian (2013) described a study with two groups of pianists who practiced every day, one physically and one mentally. In the study, it was found that the motor cortex associated with the fingers in both groups increased in size. Surprisingly, the mental practice seemed to have as much impact on the brain as the physical one. You can change your brain, just by thinking about music! This shows that people who use mental practice are creating the same, or similar, neuroplasticity that is developed through deliberate physical practice.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”The Brain in Learning”]

The Motor Cortex:

The motor cortex is an area of the brain located in the cerebral cortex and is responsible for controlling voluntary movements. Through neuroplasticity the motor cortex adapts, strengthening the correct signal and weakening the incorrect signal.

Fig. 4: “Motor Cortex Two”

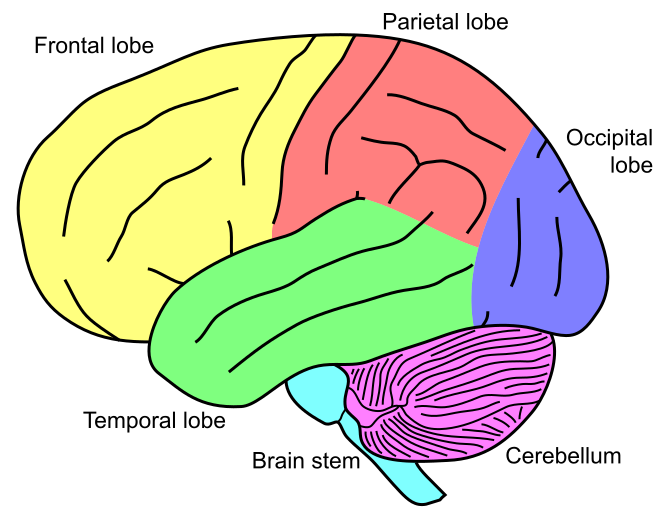

The Cerebellum:

The cerebellum is a part of the brain located towards the back of your head, behind the spinal cord, and is responsible for coordinating movements. In learning, the cerebellum acts as an error detector (Gebrian, 2013). Having an error detector in your learning is beneficial because it encourages the development of positive signals being sent from the brain and discourages incorrect signals. The cerebellum works hand in hand with the motor cortex!

Fig. 5: “Lateral view of a human brain, telencephalic lobes, cerebellum and brainstem colored”

Together, the cerebellum and motor cortex work to enhance retention in learning and develop positive habits when performing. The cerebellum works as an error detector in the brain sending signals to the motor cortex when a mistake is made. Through correct practice, the motor cortex will be able to use the signals from the cerebellum and strengthen the correct signals sent to the muscles to make the instrument work!

[/toggle]

But why is this any different from physical practice?

According to the study mentioned earlier executed by Spittle (2010), there are NOT major differences in improvement between physical practice and mental practice, both with retention and immediate results. A study performed by Cahn (2008) with a focus on jazz musicians arrived at a similar conclusion.

So why should I use mental practice?

Mental practice is helpful in combination with other forms of practice, but can also be beneficial as a replacement to some physical practice. Replacing some of your physical practice with mental practice can help to prevent overuse injuries!

How do I use mental practice?

Just like any new experience, mental practice takes practice. There are different forms of mental practice such as auditory and motor imagery and it will take time to develop the skills to have effective imagery-based learning. Start by practicing with a piece you know well; hear how it goes in your head, and imagine your body moving along to the performance. From there you will begin to develop the skills of a strong mental representation, gradually incorporating this style of learning with works that are less familiar to you. Be sure to do this slowly as it will take time to develop this imagery. And remember, you perform what you practice, so be deliberate with your approach to imagery-based practice and take it one step at a time!

Combined Practice

Combined Practice is a form of practice using multiple means of learning together. For example, using mental practice, physical practice, and singing for learning one passage of music. Kristian Steenstrup presented a study in which 50 university-level trumpet players performed and used different practice methods for short excerpts. The student began by sight reading an unknown excerpt, and then applied a learning technique: Physical Practice, Mental Practice, Singing, Combined Practice, or No Practice, to each of the 5 excerpts they received.

According to this study:

“a strategy combining physical practice, imagery and singing was just as efficient as extensive and repetitive physical practice in improving both the overall performance and the pitch accuracy, and more efficient than practice strategies that relied on motor/auditory imagery or overt singing/solfege alone. Moreover, the combined practice strategy produced a significantly higher level of musical expression as compared to all other four practice strategies” (Steenstrup, p. 15).

Based on this research combined practice is proven to significantly enhance musical expression. This shows that while you can still learn to have the same growth with the accuracy of pitches and rhythm, using a combined form of practice enhances the musicality of the performance.

Another study that shows the significance of Combined Practice is Cahn’s study (2008) in the context of learning a tonal jazz passage. This study focused on the number of errors in performance and showed that physical practice led to the most immediate improvement in errors, followed closely by combined practice 66% physical and 33% mental. Even though physical practice showed immediate improvement in errors, combined practice offers the high advantage of distributing physical practice with other forms of practice, having the potential to diminish physical strain and prevent injuries. Additionally, music is more than playing correct notes, and as mentioned earlier, combined practice was shown to improve musical expression (Steenstrup et al., 2021).

How does this work?

As mentioned as a criterion of Deliberate Practice, learning produces and depends on effective mental representations (Ericsson, 2016). Using combined forms of practice (physical, mental, and singing) encourages the development of mental representations through mental practice, and illustrates the strength of the mental representation through singing. Through physical practice alone, mental representations develop over time, but practicing directly to develop these representations allows for deeper learning and faster neuroplasticity.

Further Learning Techniques

Combined with mental practice and singing, here are some learning techniques that can be applied to physical, mental, and singing practice to deepen your learning.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Interleaved/Random Practice”]

Interleaved Practice is a form of practice that shifts between a number of different skills being practiced (Steenstrup et al., 2021, p. 3). Rather than working on one movement of an etude for 30 minutes, you practice five different sections of music for 6 minutes each. Random practice has been shown to have significant improvements in performance and aid in retention (Coughlan et al., 2014; McBride & Rothstein, 1979; Overdorf et al., 2004; Vera et al., 2008).

[/tab]

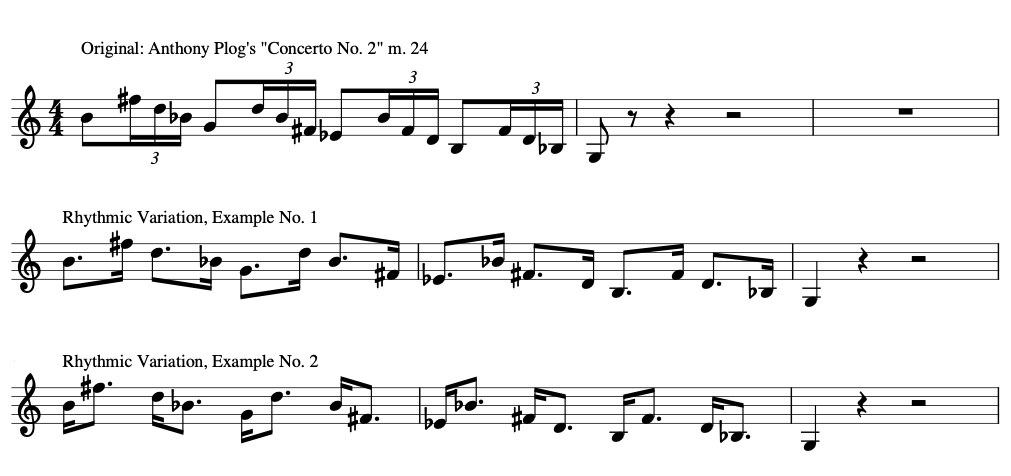

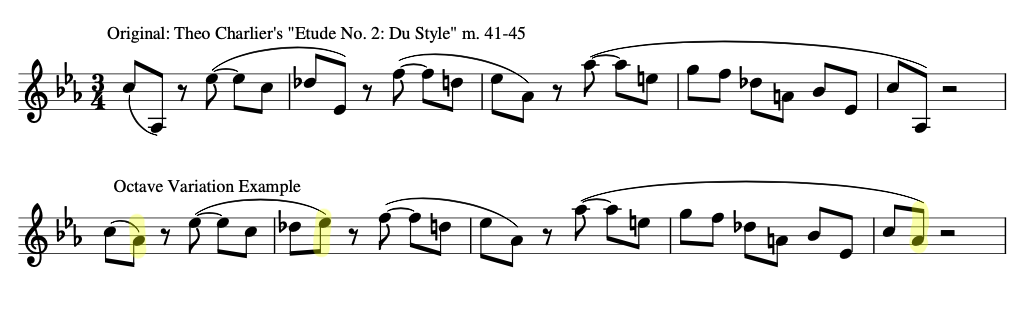

[tab title=”Varied Practice”]

Varied practice refers to modifying an exercise or piece to address new aspects of playing. This can mean changing the rhythm, octave, articulation, key, style, and more! Varied practice aids in more development since it creates a “high contextual interference” (Steenstrup et al., 2021, p. 3), or works the brain differently to cause neuroplasticity.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Singing”]

Singing in learning relates to the auditory imagery of music. Steenstrup (2021) states that singing “will tell the performer whether the aural image of the music is correct” (p. 3). Singing is used as a way to guide the brain toward the musical goal. By singing, musicians are demonstrating the characteristics of the music they are attempting to evoke without the constraints of their instruments.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Combined Practice and Learning Retention

Now that I know what combined practice is, how will it help me remember what I practice in my performances?

First, let’s start with a definition of retention: a). the continued use, existence, or possession of something; b.) the ability to keep or continue having something (Carter, 1999). Most of the studies in this article delve into the topic of combined practice, but they focus on combined practice with immediate results. In their study on the impact of combined practice on retention in the context of learning soccer, Vera and colleagues showed that combined methods of practice and interleaved practice improve retention more than blocked practice. According to Vera (2008), “when a pre-posttest comparison was made of means of the three groups, those who had random practice and combined methods showed significantly better scores on both skills, but not the blocked practice group” (p. 457). Based on this study, combined methods of practice and interleaved practice demonstrate improvements in retention. Using these methods of learning increases retention since learners are repeatedly asked to reestablish responses in different activities (Vera et al., 2008). Recreating the response necessary for each task a number of times leads to improved learning and retention. By constantly shifting between mental practicing, singing, and physical practicing, the brain is repeatedly reestablishing responses and working with a high contextual interference causing the brain to work harder, resulting in more retention in learning.

What does this mean?

While there have been no studies focusing on the effects of combined practice and musical long-term retention, there have been proven benefits of combined practice and non-musical retention. Combined practice is also shown to have benefits for learning and musicality and by requiring less time physically practicing the instrument, there is a lower chance of developing overuse injuries.

Big Takeaway

You perform what you practice! Be healthy and smart in your practice sessions and you will see growth in your development. You don’t need to practice 8 hours a day to see improvement; focus on a high quality of practice rather than the quantity. Be willing to use new forms of practice! Training your brain (neuroplasticity) is the key to faster and more solidified progress.

Author: Christopher Keach

[accordion]

[toggle title=”References”]

References

Altenmüller, E. & Furuya, S. (2017). Apollos gift and curse: Making music as a model for adaptive and maladaptive plasticity. e-Neuroforum, 23(2), 57-75. https://doi.org/10.1515/nf-2016-A054

Cahn, D. (2008). The effects of varying ratios of physical and mental practice, and task difficulty on performance of a tonal pattern. Psychology of Music, 36(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607085011

Carter, R. (1999). Retention. Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary. Retrieved from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/retention

Coughlan, E. K., Williams, A. M., McRobert, A. P., & Ford, P. R. (2014). How experts practice: A novel test of deliberate practice theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40(2), 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034302

Ericsson, A., & Pool, R. (2017). Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Gebrian, M. (2013). What musicians can learn about practicing from current brain research. Molly Gebrian, Violist. https://mollygebrian.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/what-musicians-can-learn-about-practicing-from-current-brain-research.pdf

McBride, E. R., & Rothstein, A. L. (1979). Mental and physical practice and the learning and retention of open and closed skills. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 49(2), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1979.49.2.359

Niamh M. Tunney, Catherine E. Arnold & Leslie M. Gimbel (2011) Mental Practice to facilitate learning when physical practice is unsafe: A pilot study. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Geriatrics, 29(3), 243-254, https://doi.org/10.3109/02703181.2011.599481

Overdorf, V., Page, S. J., Schweighardt, R., & McGrath, R. E. (2004). Mental and physical practice schedules in acquisition and retention of novel timing skills. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 99(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.99.1.51-62

Spittle, M., & Kremer, P. (2010). Mental practice and the retention of motor learning: A pilot study. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 110(3 Pt 1), 888–96. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.110.3.888-896

Steenstrup, K., Haumann, N. T., Kleber, B., Camarasa, C., Vuust, P., & Petersen, B. (2020). Imagine, sing, play- combined mental, vocal and physical practice improves musical performance. Frontiers in Psychology. 12:757052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.757052

Vera, J. G., Alvarez, J. C. B., & Medina, M. M. (2008). Effects of Different Practice Conditions on Acquisition, Retention, and Transfer of Soccer Skills by 9-Year-Old Schoolchildren. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 106(2), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.106.2.447-460

[/toggle]

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Images”]

Images

- Neuron by NickGorton~commonswiki, licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- “Brain Exercising” licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication

- Piano Player by @Mohamed Hassan, licensed under Creative Commons CC0.

- “Motor Cortex Two” by SeanPatrickConnolly, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

- “Lateral view of a human brain, telencephalic lobes, cerebellum and brainstem colored” by NEUROtiker, licensed under Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-2.5

- Learning by @Mohamed Hassan, licensed under Creative Commons CC0.

- “Pamela Frank | VC Masterclass | How Many Hours Should One Practice Every Day?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koPdt473oBI

[/toggle]