Focal what?

If you have asked this question, you are not alone. Many professional musicians have never heard of focal dystonia unless they have suffered from it or know of someone who has. Nevertheless, it is a serious, potentially career-ending disorder that every musician needs to be made aware of.

This blog post will focus primarily on musician’s hand dystonia, a disorder found in pianists, guitarists, and string and wind players. It manifests itself initially in unresponsive fingers, often leading musicians to believe that it is simply a question of being out of shape or needing more practice.

Symptoms

How does focal dystonia manifest itself? What are its symptoms?

Brandfonbrener and Kjelland (2002) describe hand focal dystonia’s classic characteristic muscular spasms as “an inability to control a finger or fingers, primarily in one hand, which curl into the palm, often accompanied by a reciprocal extension of one or more of the other fingers” (p. 9).

Hand focal dystonia is usually painless and is not alleviated by practicing either more or less. It is task-specific in that it involves music making but usually does not affect other hand activities. It is centered in the performer’s most active hand or hands: the right hand in pianists, the left hand in string players, and either hand in guitarists (Butler, 2010, p. 368).

Altenmuller and Jabusch (2010) estimate that approximately one percent of all professional musicians suffer from focal dystonia (p. 31). Although this percentage might seem to be small, many well-known musicians have been afflicted with this disorder, among them pianists Gary Graffman and Leon Fleisher as well as violinist Peter Oundjian (Horvath, 2010, p. 72). Unfortunately, as we shall see, this disorder is difficult to diagnose and so epidemiological data is often imprecise (Watson, 2009, p. 262).

So – what causes focal dystonia?

In the past, focal dystonia was believed to have a psychological source. Today, the prevalent theory is that it is caused by a neurological malfunction although most therapists do believe that the condition can be exacerbated by psychological factors (Lie-Nemeth, 2006, p. 782).

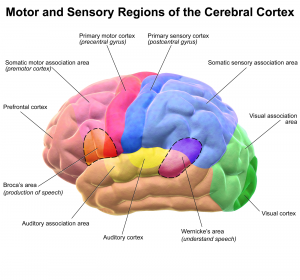

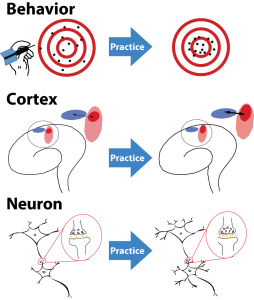

In their day-to-day practice and in performance, musicians are constantly required to activate adjacent fingers rapidly and accurately. Musical learning causes the circuitry of the brain to adapt to what is being learned and this adaptability is referred to as neuroplasticity.

Music making can create a healthy model of neuroplasticity in the motor cortex, allowing for the performance of highly complex passagework. The brains of highly trained, healthy musicians show an increase in grey nerve cell matter in the sensory-motor and auditory areas of the brain. (Altenmuller and McPherson, 2008, p. 122). The same authors also state that instrumental practice causes the hand area in the motor cortex to be enlarged (p.136).

Pianists and violinists display both similar and different characteristics of neuroplasticity. In both types of instrumentalists, the front part of the corpus callosum, a band of nerve fibers joining the two hemispheres of the brain, is enlarged (Altenmuller and McPherson, 2008, p. 136). This is probably in response to high demands for coordination of the two hemispheres in the performance of music. It is necessary for the hemispheres to be able to inhibit themselves efficiently in order to coordinate their motor areas so that there can be selective action in one area and not in another. These inhibitory capabilities are enhanced in musicians through prolonged practice (Jancke, 2006, p. 158).

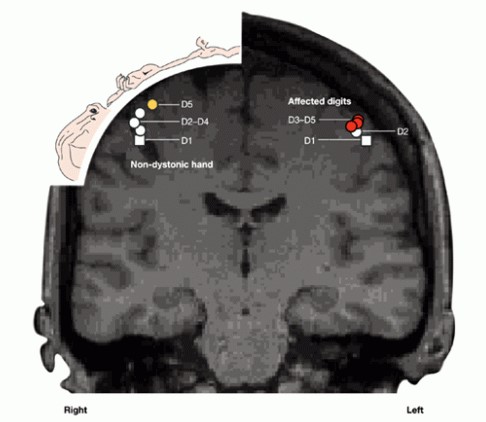

Butler (2010) describes the onset of musicians’ hand focal dystonia as happening when “repetitive movements induce stereotypical feedback messages, which lead to disorganisation in the sensory cortex (of the brain) and a failure in sensorimotor integration (communication between the sensory and motor areas of the brain), which in turn induces lack of motor coordination” (p. 372). As Byl and Priori (2009) state, “the Hebb rule is: ‘Neurons that fire together wire together’ ” (p. 297), and so maladaptive neuroplasticity manifests itself.

Watson (2009) describes what follows: “the receptive fields of the nerve cells that map the fingers onto the cortex can be enlarged…resulting in considerable overlap between the representation of adjacent fingers” (p. 264). When the receptive fields cover several fingers, the brain can no longer distinguish one digit from another. Consequently, agonist muscles, which initiate a movement, and antagonist muscles, which oppose or control that movement, contract at the same time when normally one set would be inhibited while the other was active (Chen and Hallett, 1998, p. 103).

Other Causal Factors

Many researchers, including Rosenkranz (2009), have theorized that hand focal dystonia can have several causal factors. Altenmuller and Jabusch (2010) state that a genetic history of dystonia may have an influence. Poor posture and biomechanical limitations can also play a part (Tubiana, 2003, p. 166).

Video demonstrating musicians’ hand dystonia and biomechanical limitations

What about a diagnosis?

Musicians with hand focal dystonia must be evaluated while playing their instruments in order for a proper diagnosis to be made. Rosset-Llobet et al. (2009) note that this is because the disorder is task-specific and very often the symptoms can only be observed in a performance setting (p. 867).

Some musicians manifest symptoms when playing classical repertoire but not when improvising. Altenmuller and Jabusch (2010) remark on the fact that jazz musicians seem to be less vulnerable to focal dystonia, perhaps because improvisation frees them from the unforgiving expectation of perfect musical reproduction that is involved in the performance of classical music (p. 35).

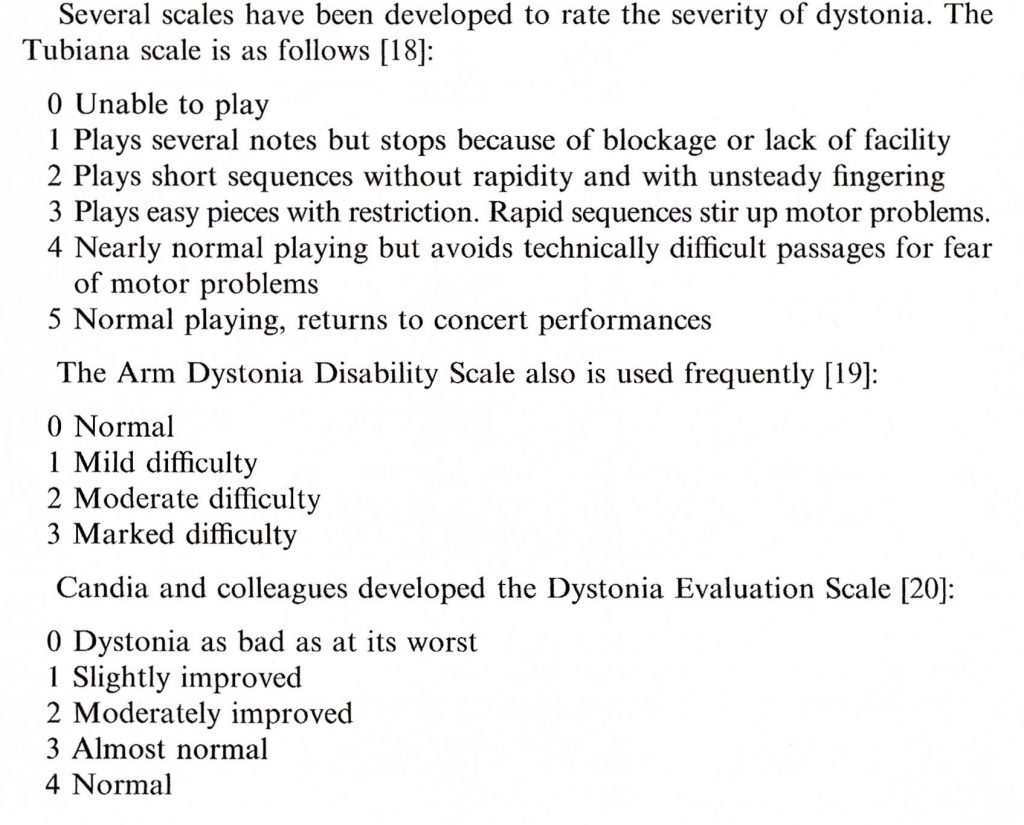

When a diagnosis is made, the severity of the focal dystonia can be rated. Lie-Nemeth (2006) describes several scales used to measure the extent of the disorder:

Am I at risk?

What exactly are some of the issues that might be instrumental in triggering focal dystonia?

Certain predisposing factors seem to be at play. Male professional musicians appear to be more susceptible to the disorder than their female counterparts. It is known that hand focal dystonia often appears in musicians when they are in their thirties or forties (Brandfonbrener and Lederman, 2002, p. 1016).

As mentioned earlier, Altenmuller and Jabusch (2010) have noted that genetic predisposition may contribute to the emergence of the disorder. They also mention that “traumatic injuries, nerve entrapment or overuse injuries” may precede the development of focal dystonia in musicians (p. 33).

The excessive perfectionism often required from professional musicians and the anxiety associated with that perfectionism can play a part as well. A study conducted by Jabusch et al. (2004) demonstrated that musicians with focal dystonia experience more anxiety than participants in control groups. However, some degree of anxiety would seem to be expected in musicians who were finding it extremely difficult to practice and to perform.

Video illustrating Leon Fleisher’s experience with focal dystonia

Practice makes imperfect

What do music students, professional musicians and music teachers need to know about focal dystonia and how to prevent it?

First and foremost, learning how to practice effectively is extremely important. If excessive perfectionism and the resulting obsessive practice behaviors can contribute to this disorder, they must be recognized and dealt with. Unfortunately, as Brandfonbrener and Lederman (2002) note, “in the context of injuries and their prevention, the discussion of technique and music pedagogy should be understood as being from a physiologic point of view, which may well not always coincide with accepted and even proven teaching methods” (p. 1020).

Teaching Approaches for Neurological Health

What do teachers need to tell their students about healthy practicing and performance?

Butler (2010) suggests varying the “speed and force of the repetitive motor tasks” and encouraging music students to improvise in order to free themselves from the printed score (p. 386).

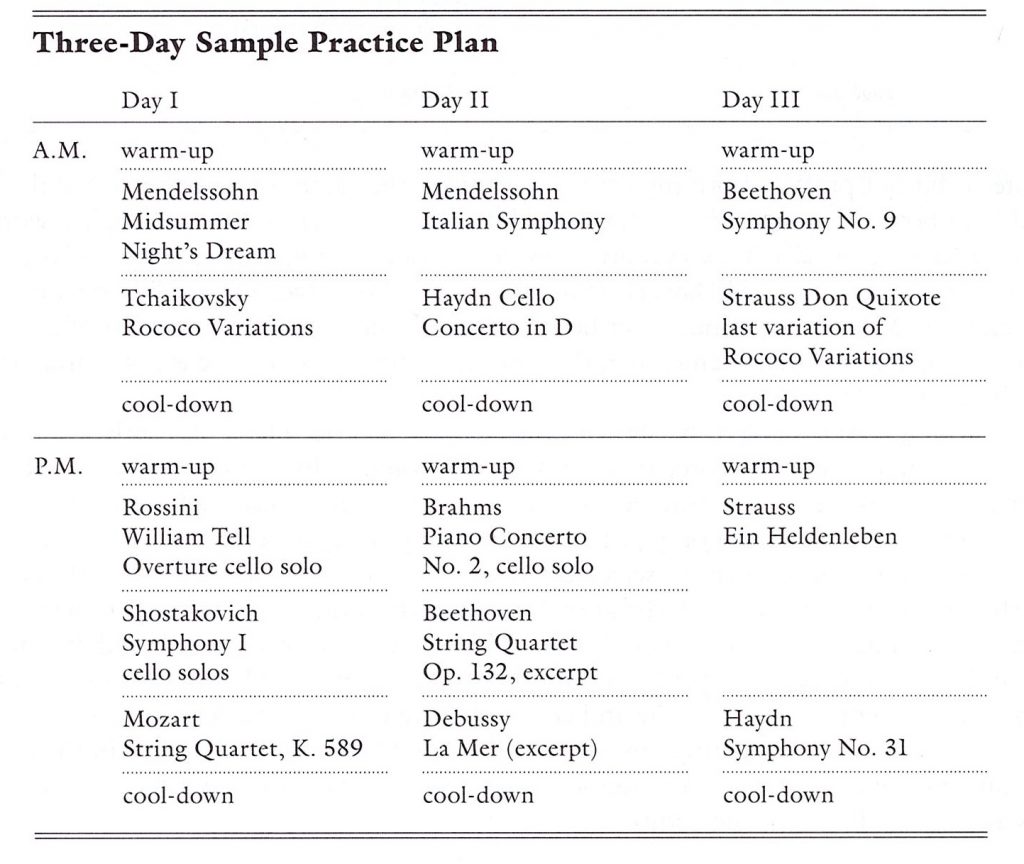

Horvath (2010) says that every musician can benefit from structured practice with a warmup, a practice session of varied repertoire, breaks in longer practice periods and a cool-down at the end of the session (p. 178-180). She suggests that the musician should make a checklist of repertoire to be practiced in each session as this ensures a structured practice period (p. 181).

Horvath (2010) also mentions varying the repertoire to be practiced, alternating slower and faster passagework, and working on repertoire with different technical challenges that can help concentration and exercise different muscles, making the session easier on both the body and the brain (p. 181).

Horvath along with Barry and Hallam (2011) stress the value of mental practice – thinking about and rehearsing the music away from the instrument. All of these techniques can be adapted and used by musicians of all ages.

Video explaining brain plasticity in relation to memory

My fingers won’t work! What do I do now?

Focal dystonia has no definitive cure at the present time. There are, however, many treatments which have been tried by musicians with more or less success.

[toggle title=”Therapeutic drugs”]Watson (2009) lists a number of drugs which can be used to treat the symptoms. Benzodiazepines and baclofen are conducive to muscle relaxation as they reduce the activity of motor neurons. Anticholinergic drugs such as trihexphenidyl can be used to prevent over-activity in brain circuitry as a result of low levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Drugs which have the same effect as dopamine can be prescribed as well. Botulinum toxin injections can alleviate focal dystonia’s debilitating muscle contractions but can also weaken muscles to such an extent that playing may be affected (p. 268).[/toggle]

Butler (2010) comments that surgery to relieve symptoms is a controversial intervention and many researchers believe it should be used sparingly if at all (p. 374).

Sensory Re-education Techniques and other Physical Treatments

Sensory re-education involves ‘rewiring’ the brain by using repeated motor tasks to reverse the maladaptive plasticity which has led to focal dystonia. Byl and Priori (2006) describe such a therapy and state that “any effective therapy must re-differentiate the hand representations (and this) can only be achieved by intensive, goal-oriented, progressive learning-based training” (p. 300).

Candia (2009) gives a description of sensory motor retuning (SMR) which involves immobilizing the compensatory curled finger in a splint so as to exercise the dystonic or extended finger and the other fingers of the hand (p. 79-80).

Complete immobilization of the dystonic hand has also been attempted with moderate success (Butler, 2010, p. 380).

Sakai (2006) has developed a slow-down exercise therapy which involves practicing at a speed that is below the tempo threshold required to trigger dystonic symptoms (as cited in Butler, 2010, p. 381).

Instrument modification has also been experimented with (Butler, 2010, p. 283-284).

Various sensory tricks can be used to alter the sensations of actually playing an instrument. Horvath (2010) describes several ways of altering sensory input from the fingers, among them playing using latex or rubber gloves, using an abrasive on the fingertips to make them more sensitive before playing, and covering piano keys with textured tape (p. 76).

Tubiana’s (2003) neuromuscular rehabilitation therapy concentrates on addressing the biomechanical and psychological factors which the author believes to be dystonic triggers.

Many musicians have improved their symptoms through a multidisciplinary treatment approach with the help of neurologists, therapists, psychologists, and teachers. Each treatment program needs to be tailored to the individual involved as ‘no one size fits all.’

Finally, a number of associations have been formed to serve as resource centers for those dealing with focal dystonia. One of the most prominent of these is the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation.

So where do we go from here?

The diagnosis of hand focal dystonia has abruptly ended many professional musical careers. How do we come closer to understanding what its causes really are and how to treat and prevent it? Neuroscience is beginning to find the answers through new brain imaging techniques. As brain imaging techniques become more and more sophisticated the mystery of focal dystonia may come closer to being solved.

[toggle title=”Brain scan techniques”]Flohr and Hodges (2002) list a number of imaging tools including electroencephalography (EEG), event-related potentials (ERP), magnetoencephalography (MEG), superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The authors describe each of these in detail (p. 994-996). [/toggle]

Finally, awareness and prevention of hand focal dystonia is of the utmost importance. Musicians must become more knowledgeable about all types of self-induced injuries, including focal dystonia. Above all, we must find ways to effectively encourage physically and neurologically healthy practice techniques in both amateur and professional musicians, young and old.

References

Altenmuller, E. (2010). The musician’s brain as a model of adaptive and

maladaptive plasticity. In F.C. Rose (Ed.), Neurology of music (pp. 103-

114). London, UK: Imperial College Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/9781848162693_0006

Altenmuller, E., & Jabusch, H.C. (2010). Focal dystonia in musicians:

Phenomenology, pathophysiology and triggering factors. European

Journal of Neurology, 17, 31-36.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03048.x

Altenmuller, E., & McPherson, G.E. (2008). Motor learning and instrumental

training. In W. Gruhn & F.H. Rauscher (Eds.), Neurosciences in music

pedagogy (pp. 121-143). New York, NY: Nova Biomedical Books.

Barry, N.H., & Hallam, S. (2002). Practice. In R. Parncutt and G. McPherson

(Eds.), The science and psychology of music performance: Creative

strategies for teaching and learning (pp. 1-23). Published to Oxford

Scholarship Online: October 2011.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195138108.003.0010

Brandfonbrener, A.G., & Kjelland, J.M. (2002). Music medicine. In R.

Parncutt and G. McPherson (Eds.), The science and psychology of music

performance: Creative strategies for teaching and learning (pp.1-21).

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: October 2011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195138108.003.0006

Brandfonbrener, A.G., & Lederman, R.J. (2002). Performing arts medicine.

In R. Colwell, C.P. Richardson & Music Educators National Conference

(U.S.) (Eds.), The new handbook of research on music teaching and

learning: A project of the Music Educators National Conference (pp.

1009-1022). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Retrieved from:

https://site.ebrary.com/lib/mcgill/reader.action?docID=10590426&ppg=1014

Butler, K. (2010). Focal hand dystonia affecting musicians. In F.C. Rose

(Ed.), Neurology of music (pp. 367-392). London, UK: Imperial College

Press. https://doi.org/10.1142/9781848162693_0024

Byl, N.B., & Priori, A. (2006). The development of focal dystonia in musicians

as a consequence of maladaptive plasticity: Implications for intervention.

In E. Altenmuller, M. Wiesendanger, & J. Kesselring (Eds.), Music, motor

control and the brain (pp. 293-305). Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199298723.003.0019

Candia, V. (2009). Playing beyond the limits of health: Loss and regain of

hand control in professional musicians suffering from musicians’ cramp.

In A. Mornell (Ed.), Art in motion: Musical and athletic motor learning

and performance (pp. 71-90). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang

GmbH Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. Retrieved from:

https://site.ebrary.com/lib/mcgill/reader.action?docID=10954823&ppg=73

Chen, R., & Hallett, M. (1998). Focal dystonia and repetitive motion

disorders. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 351, 102-106.

Flohr, J.W., & Hodges, D.A. (2002). Music and neuroscience. In R. Colwell,

C.P. Richardson & Music Educators National Conference (U.S.) (Eds.),

The new handbook of researchon music teaching and learning: A project

of the Music Educators National Conference (pp. 991-1008). Oxford, UK:

Oxford University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195304565.003.0002

Horvath, J. (2010). Playing (less) hurt: An injury prevention guide for

musicians. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Books.

Jabusch, H.C., Muller, S.V., & Altenmuller, E. (2004). Anxiety in musicians

with focal dystonia and those with chronic pain. Movement Disorders, 19,

10, 1169-1175. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20110

Jancke, L. (2006). The motor representation in pianists and string players.

In E. Altenmuller, M. Wiesendanger, & J. Kesselring (Eds.), Music,

motor control and the brain (pp. 153-169). Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199298723.003.0010

Lie-Nemeth, T.J. (2006). Focal dystonia in musicians. Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 17, 4, 781-787.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2006.06.003

Rosenkranz, K. (2006). The neurophysiology of focal hand dystonia in

musicians. E. Altenmuller, M. Wiesendanger, & J. Kesselring (Eds.),

Music, motor control and the brain (pp. 283-292). Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199298723.003.0018

Rosset-Llobet, J., Candia, V., Fabregas, M.S., Dolors, R.C.D., & Pascual-Leone,

A. (2009). The challenge of diagnosing focal hand dystonia in musicians.

European Journal of Neurology, 16, 7, 864-869.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02610.x

Tubiana, R. (2003). Prolonged neuromuscular rehabilitation for musician’s

focal dystonia. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 18, 4, 166-169.

Retrieved from:

https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/journalviewer.aspx?issue=1078&article=889&action=1

Watson, A.H.D. (2009). The biology of musical performance and

performance-related injury. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

Media

Motor and Sensory Regions of the Cerebral Cortex By BruceBlaus. When using this image in

external sources it can be cited as:Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen

Medical 2014″. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

– Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31574253

(Figure 3)

Brain Neuroplasticity after Practice By Bokkyu Kim at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54702646

(Figure 4)

Wilson, F. (2010, Nov. 14). Introduction to musician’s hand dystonia. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T7OpC9-Gd9g

De Castro, M. (2017, April 6). Factors influencing the onset of focal dystonia (Figure 7)

PBS News Hour. (2011, July 18). Piano virtuoso Fleisher on overcoming disability that nearly

silenced career. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZLvhZvO2v4

Moffit, M. & Brown, G. (2013, January 17). The scientific power of thought. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-v-IMSKOtoE

De Castro, M. & R. (2017, April 6). Characteristics of focal dystonic hands & treatments for focal dystonia.

(Figures 1, 2, 9, 10 & 11)