When musicians start to feel pain or tingling while playing, very often we’ll seek out a doctor or physiotherapist for relief. Musicians want results that are fast, so that we can get back to playing as soon as possible, while also being safe, so we don’t put a long term playing career at risk. However, this sort of thinking could actually be perpetuating an existing injury or making it worse.

There are a variety of injuries and disorders that are found in musicians, such as focal dystonia or De Quervain’s. A playing-related musculoskeletal disorder, or PRMD, is one kind of injury common in musicians. A PRMD can be present if you have pain, weakness, lack of control, numbness, tingling, or other symptoms that interfere with your ability to play your instrument at the level to which you are accustomed (Zaza, Charles, & Muszynski, 1998).

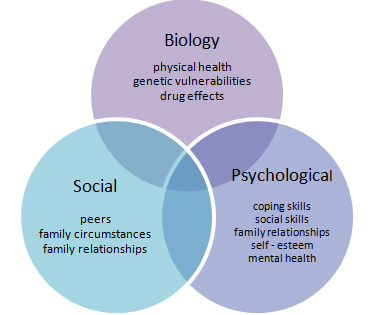

Although many of these symptoms seem physical, pain itself is the unpleasant emotional response we feel in response to stimuli. Pain is subjective, and can be affected by a variety of psychological, sociological and behavioural processes, as outlined in the Biopsychosocial Model of Health (Engel, 1977; Engel, 1981). This means that pain can be affected by memories, thoughts and personalities, to name a few.

With musicians shown to be three times more likely to suffer from depression than the general population, a relationship between the epidemic proportion of injuries (over 50%!) and mental illness needs a closer look (Musgrave & Gross, 2016; Ackermann, Driscoll & Kenny, 2012). Researchers have started to show the links between PRMDs, depression and music performance anxiety (Kenny & Ackermann, 2013). To understand this correlation, I’ll start by taking a closer look at what’s happening in the brain when someone experiences pain.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Understanding pain and the brain”]

So what is actually going on in the brain and the body when a musician is experiencing pain, say from a PRMD?

Again, it’s important to remember that pain is a subjective experience and not the actual physical event of injury. Pain is the unpleasant emotional response we feel in response to stimuli (Merskey, 1979).

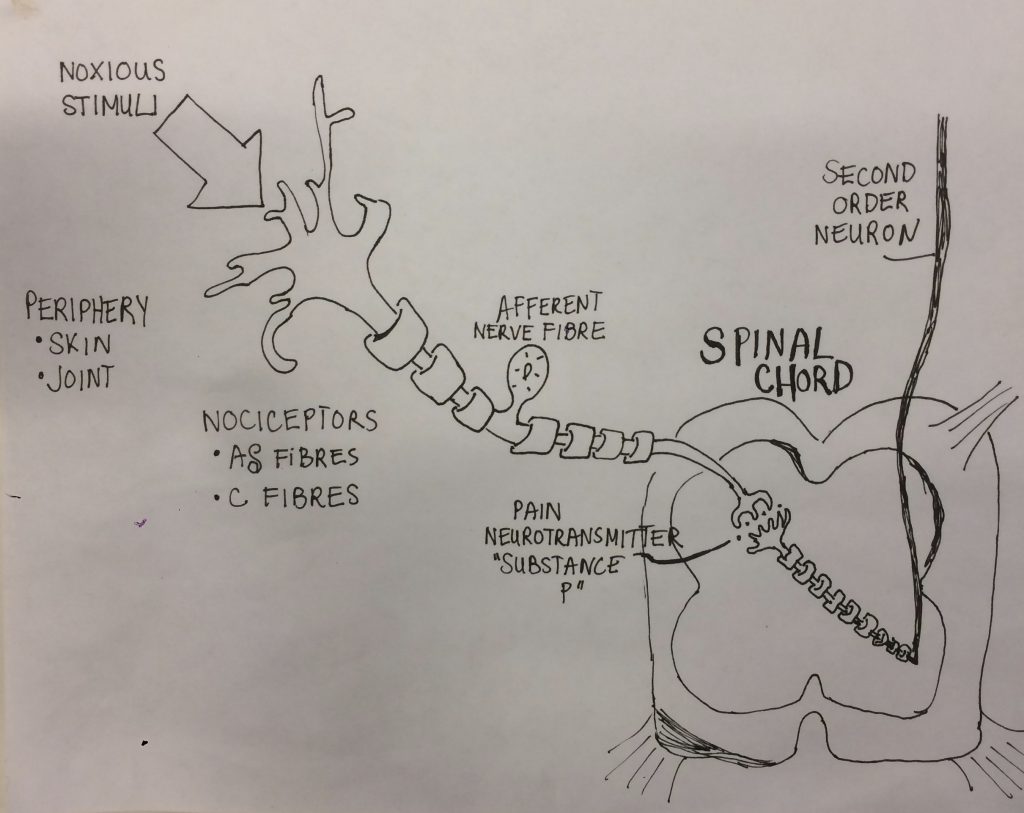

According to Fein (2012), pain occurs at the same time as nociception, which refers to signals arriving to the brain because of the activation of specialized, sensory receptors (called nociceptors) relaying information about tissue damage. Nociceptors, the pain-sensing nerve cells, will release chemicals called pain neurotransmitters in the spinal cord.

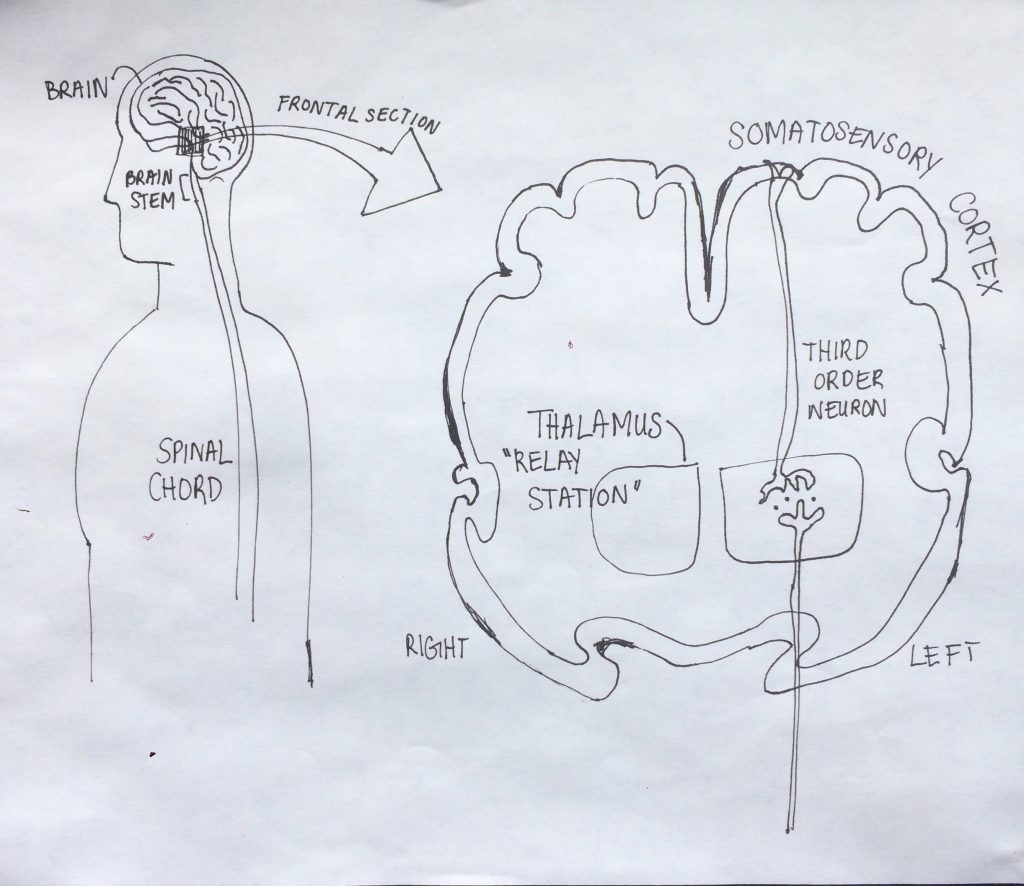

The information is sent to the thalamus of the brain where the thalamus relays information to the somatosensory cortex, the part of the cerebral cortex that processes sensation.

From there, the information may be taken to other parts of the brain that respond to motor control or emotional response in order for your brain to process a reaction. For example, if you placed your hand on a hot stove, you would react by removing your hand from the stove while simultaneously having the emotional response of feeling pain and fear (Fein, 2012).

There are two types of nociceptors: Alpha-delta fibres, which transmit sharp and localized pain very quickly to the brain, and C fibres, which transmit unlocalized pain, like throbbing pain that may last a lot longer, at a slower rate to the brain. C fibres are the nociceptors being activated in pain resulting from a PRMD, which lasts longer than the initial stimuli.

Still confused like I was at first? Watch this quick 90 second recap:

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”The psychology of pain”]

The psychology of pain can be narrowed down to three main categories (Morley, 2002):

- Interruption, or the impact of pain on the disruption of attention and its behavioural consequences on a moment-to-moment basis. For a musician, this could be when pain causes us to have to stop practicing or rehearsal for the day.

- Interference, or continued disruption that has significant consequences on behavioural and cognitive performance. It’s also when a person fails to complete tasks effectively or performs them in a degraded manner that is unacceptable to them or members of their social group. For a musician, this could be anything from not performing to their own standards at a lesson or rehearsal because of pain, to not performing to the standards of others at an audition, exam or graded recital.

- Identity, or how repeated interference of key tasks impacts upon the person’s sense of who they are, and perhaps more importantly, who they might become by distorting their vision of their future and reshaping their view of the past. For a musician, this is seen when injuries may impact how they view themselves as a musician and their future performing career, and is especially important because playing our instrument can be closely tied to our sense of self.

Chronic pain, or pain that has lasted for more than 3 months, has a profound effect on all 3 categories. Part of the definition of PRMDs is that the pain is chronic, as opposed to acute pain that lasts for no more than 6 weeks (Zaza, Charles, & Muszynski, 1998). Repeated interference of daily tasks that are essential to achieving various life goals—for a musician this would be music making or playing our instrument—impacts on our sense of self and our future plans. It can also impact who we might become by distorting our perception of the future and reshaping the past.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”How do PRMDs relate to depression and anxiety?”]

A recent study on 377 professional orchestral musicians showed that severity of the PRMD correlated with depression and music performance anxiety (Kenny & Ackermann 2013). In research on chronic pain, depression and anxiety are also frequently correlated with the pain experience (Morley, 2002; Morley, Davies & Barton, 2005; Turk & Okifuji, 1996)

The relationship between pain, depression and anxiety can work simultaneously, in that one can cause or influence the other or vice versa. This video will give you a generalized look at the relationship between chronic pain and depression:

Chronic pain, unlike acute pain, can be perpetuated not only by the mechanical and physiological processes that were described in “Understand pain and the brain”, but also for psychological and sociological reasons. These can be:

- Emotions

- Social and environmental context

- Sociocultural background

- The meaning of pain to the person

- Beliefs, attitudes, and expectations

- Biological factors

Melzack’s pain theory (2001) of the body-self neuromatrix shows that the pain experience is part of many systems that include multiple sensory inputs, memories of past experiences, personal and social expectations, genetic contributions, gender, ageing, and stress patterns involving the endocrine, autonomic, and immune systems (Melzack, 2001).

These “reactions to pain” are now integral to understanding pain processing and explain the difference between pain perception and pain appraisal. Pain perception is the interpretation of nociceptive input that identifies pain as sharp, burning, punishing, etc., where as pain appraisal is the meaning attributed to pain and influences of subsequent behaviour.

For example, in a PRMD, pain is perceived as weakness, tingling, or numbness, but pain is appraised in a variety of different ways depending on the musician. The general line of thought in pain appraisal is: “This pain means this to me so I will or won’t do this” (Turk & Okifuji, 2002).

One form of pain appraisal is fear-avoidance, when the fear of re-injury or fear of perpetuating the injury causes hypervigilance or avoidance of activities believed to be associated with causing the pain. In a musician, fear-avoidance might take the form of avoiding practicing or playing for fear that it will worsen an injury or cause re-injury. Fear is a natural consequence of pain, because it helps in an acute pain situation where a fight-or-flight response is needed. But in the case of chronic pain, it can impede recovery and cause anxiety (Turk & Okifuji, 2002; Lucchetti et. al., 2012).

Pain appraisal can also be behaviours that positively impact the musician, such as taking more breaks during practice or learning to mental practice.

This video explains how people appraise pain differently:

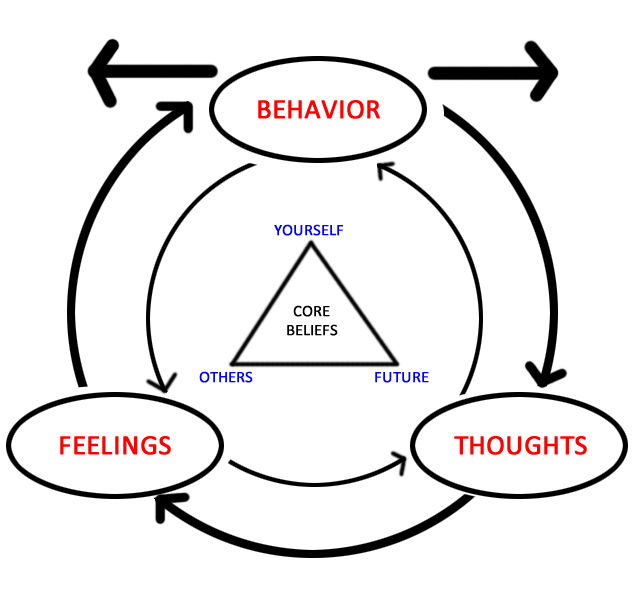

Because of pain appraisal, pain can be managed not only by physiological means, such as through physiotherapy or anti-inflammatories, but also by psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which is common in the treatment of mental illnesses like depression and anxiety (Morley, 2011).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”New treatment possibilities for PRMDs”]

A recent study showed that PRMDs might not be able to be treated effectively without considering the relationship between depression and MPA (Kenny & Ackermann, 2013). Although these kinds of treatments on musicians have yet to be assessed, treatments used for anxiety and depression have been used on patients with chronic pain for the past few decades (Morley, 2011).

Many of these treatments stress the importance of factors other than the physical condition for how patients perceive their life being interfered with by pain. Often the belief that you have been “injured” encourages patients to seek a “cure” by health professionals. This pattern of thought has resulted in a need for modification of their expectations through cognitive behavioural therapy (Turk & Okifuji, 1996).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

As already mentioned, pain can have a huge effect on your sense of self and identity. In patients with chronic pain, it can influence their sense of future selves, especially when the elimination of pain becomes their primary goal. When this goal is unattainable, it can lead to frustration, a sense of entrapment and depression (Morley, Davies, & Barton, 2005).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can be beneficial because it allows patients to believe that they aren’t helpless in dealing with their pain and don’t have to view pain as an all-encompassing determinant of their lives. CBT nurtures a sense of self-efficacy and equips the patient with skills to respond to increased levels of pain. The therapist will help reconceptualize pain as an addressable problem or series of smaller problems, instead of one overwhelming feeling.

CBT can look different for every patient, but can include alterations in lifestyle, problem solving, communication skills training, relaxation skills and homework assignments, such as keeping a diary to assess the role pain has on their lives. The therapist will also involve all members of the interdisciplinary team, such as physiotherapists, since the fear and expectancies of the patient will affect the amount of effort the patient puts in to the exercises and treatment plan.

It’s important to note that CBT does not deal exclusively with pain symptoms, but also the psychological and sociological reasons for pain, such as self-statements and environmental factors. CBT is not just about patients acquiring skills to cope with pain, but also to help them change their views of themselves and their pain and to assert active control. In this sense, the ‘cure’ does not come from a health care professional, but from the person themselves, which is proven to have more effective results (Morley, Davies, & Barton, 2005; Sutherland & Morley, 2007).

This video accurately demonstrates how CBT is used to treat chronic pain:

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”The future of PRMDs: Helping students who are injured”]

Hopefully you’ve seen from this blog post how interconnected our minds and bodies are in relation to pain and musicians’ injuries, specifically PRMDs. This new way of approaching injuries could potentially revolutionize the way we teach music and treat musicians.

A lot of this discussion points to two psychological symptoms of pain: fear-avoidance and the enmeshment of pain and identity. Although CBT has yet to be assessed on musicians with PRMDs, it has been used on chronic pain patients with positive results in improving self-efficacy and their pain symptoms (Morley, 2011).

Music teachers may not be registered cognitive behavioural therapists, but a lot of these concepts can be applied in the teacher-student relationship, especially because of the influence teachers have on their students in many aspects of their lives. Enhancing a student’s belief in their ability to exercise control over their injury by having them try new set-ups of their instrument or by teaching them healthier practice habits would be an example of how to enhance self-efficacy in a student. Teachers can also look out for fear-avoidance in their students if they notice the student hasn’t been practicing or is holding back from playing in a lesson.

Once an injury has reached the chronic stage, teachers can look out for:

- If a student avoids practicing because they fear re-injury

- If a student avoids other activities for fear of it affecting their injury (could be physical exercise or daily tasks like washing dishes)

- If a student believes quitting their instrument is the only way to get better

- If a student loses interest in music or playing their instrument

A PRMD should be treated in the same way as chronic pain in that all treatments and health care professionals work together (Turk & Okifuji, 2003). This includes physiotherapists, doctors, counsellors, psychologists but also the teacher and other musical mentors. This way, it can be ensured that the treatments are working cohesively, instead of them working against or parallel to one another.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Reference list”]

Ackermann, B., Driscoll, T., & Kenny, D. (2012). Musculoskeletal pain and injury in professional orchestral musicians in Australia. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 27(4), 181-187.

Engel, G. (1977) The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196, 129–136. doi: http://guilfordjournals.com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/doi/abs/10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.377

Engel, G. (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 535–544. doi: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1093/jmp/6.2.101

Fein, A. (2012). Nociceptors and the perception of pain. University of Connecticut Health Center, 4, 61-67. doi: https://cell.uchc.edu/pdf/fein/Revised%20Book%202014.pdf

Gross, S.A., & Musgrave, G. (2016). Can music make you sick? Music and depression: a study in the incidence of musicians’ mental health. University of Westminister, Music Tank Publishing. London. doi: https://www-sciandmed-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/mppa/journalviewer.aspx?issue=1198&article=1962&action=1

Kenny, D., & Ackermann, B. (2013). Performance-related musculoskeletal pain, depression and music performance anxiety in professional orchestral musicians: A population study. Psychology of Music, 0(0), 1-18. doi: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0305735613493953

Lucchetti, G., Oliveira AB., Mercante, JP., & Peres, MF. (2012). Anxiety and fear-avoidance in musculoskeletal pain. Current Pain & Headache Reports, 16(5), 399-406. doi: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-012-0286-7

Melzack, R. (2001). Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain. Journal of Dental Education, 65(12), 1378-82. doi: http://www.jdentaled.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/content/65/12/1378.full.pdf

Morley, S. (2011). Efficacy and effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic pain: Progress and some challenges. Pain, 152(3), 99-106. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.042

Morley, S., Davies, C., & Barton, S. (2005). Possible selves in chronic pain: self-pain enmeshment, adjustment and acceptance. Pain, 115(1-2), 84-94. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.042

Sutherland, R., & Morley, S. (2007). Self-pain enmeshment: Future possible selves, sociotropy, autonomy and adjustment to chronic pain. Pain, 137(2), 366-377. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.023

Turk, D., & Okifuji, A. (1996). Perception of traumatic onset, compensation status, and physical findings: Impact on pain severity, emotional distress, and disability in chronic pain patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 19(5), 435-453. doi: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF01857677

Turk, D., & Okifuji, A. (2002). Psychological factors in chronic pain: Evolution and revolution. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 678-690. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.3.678

Turk, D., & Okifuji, A. (2003). A cognitive-behavioural approach to pain management. Handbook of Pain Management: Well and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain, 532-541.

Zaza, C., Charles, C., & Muszynski, A. (1998). The meaning of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders to classical musicians. Social Sciences in Medicine, 47, 2013–2023. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00307-4

Wall, P., McMahon, S., & Kotzenburg, M. (2006). Handbook of Pain Management: Well and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Image list”]

Mr.Annoying. (Own work). (2016). Figure 1: Biopsychosocial model of health, via Wikipedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Biopsychosocial_Model_of_Health_1.pn

Motyer, C. (Photographer and artist). (2017). Figure 2: Nociception and the spinal cord [photograph].

Motyer, C. (Photographer and artist). (2017). Figure 3: The pain pathway in the thalamus and the somatosensory cortex [photograph].

Urstadt. (Own work). (2015). Figure 4: Depicts basic tenets of CBT, via Wikipedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Depicting_basic_tenets_of_CBT.jpg

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Leave a Reply