* DISCLAIMER*

The following blog discusses the effects, and hypothetical applications, of multiple psychedelic compounds. All research studies referenced in this publication involved legally approved, supervised, administration of these substances. Note that many of these substances are illegal in many countries, and are illegal to possess or distribute in Canada and the United States. In no way does the author of this publication condone participating in illegal activity.

For as far back as 10,000 years (Jacobs, 2007), humans have been combining psychedelics and music in order to achieve altered states of perception as well as for therapy and healing. Though modern scientific research into the effects and applications of psychedelic compounds has been limited due to legality as well as negative social connotation, since the turn of the twenty first century there has been a marked increase in support for scientific research involving the human consumption of psychedelics. The time we are currently living in has even been referred to as the “Psychedelic Renaissance” by multiple scholars. Current research in fields as broad as neuroscience, psychiatry, cognitive science, and anthropology have provided strong evidence that psychedelics and music have a strong synergy with many potential practical benefits. From music providing a means to guide participants in the psychotherapeutic use of LSD, to Cannabis induced states of hyperfocused listening, many recent scientific discoveries have implied the need to further investigate the practical benefits of combining psychedelics with music.

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”What are Psychedelics?” state=”closed”]

Psychedelics, an umbrella term within the drug classification of hallucinogens, are most commonly understood as a variety of chemical compounds that mimic neurotransmitters, most commonly serotonin, causing a change in neurological function as the result of rerouting associate neurotransmitters from their typical functionality (Fantegrossi, 2008). The term psychedelic was originated by Humphrey Osmond in 1956, in order to give a classification to the compounds he was researching that qualitatively described their function (Carhart-Harris 2014). The word is derived from the Greek words for “mind” and “manifest”, suggesting the ability of psychedelics to manifest latent aspects of the mind (Carhart-Harris, 2014). In fact the main commonality in the pharmacology of psychedelics is their unique ability to substantially alter one’s mental state of consciousness without impairing one’s bodily function.

While there are many common attributes associated with the phenomenological experience of the psychedelic state, the individual experience, or “trip”, is highly subjective and varies greatly among individuals. The most common phenomenological attributes associated with the psychedelic state include perceptual changes (auditory, visual, and somatosensory distortions), cognitive changes, changes in mood, increased sense of mystical experience (Turton, 2015). As a result of destabilizing the traditional hierarchical structure of the brain, the psychedelic experience also is often accompanied with a sense of ego dissolution, where the individual no longer experiences a sense of self but instead temporarily perceives a sense of equality between all sensory inputs (Lebedev 2015). This is often subjectively described as a sense of connection or oneness with aspects of external reality.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”A Brief History of Psychedelics” state=”closed”]

There is significant evidence that humans have been consuming psychedelic substances for thousands of years. Archaeologists have provided fossil evidence that psychoactive plants were used in ritual ceremonies dating back as far as 10,000 years (Jacobs, 2007). Further, historical evidence demonstrates that cultural use of plants containing psychedelic compounds has taken place in cultures all over the world for at least the past 5,000 years (Jacobs, 2007). The vast majority of ritual ceremonies involving psychoactive plants have also involved the use of music. Though some of these ceremonies have continued from ancient times to the present day, such as peyote rituals in some native cultures of the Americas, many of these practices were demonized by the Christian church, and through the effects of colonialism, were widely prohibited (Jacobs, 2007).

Despite the demonization of psychedelics by the church, psychedelics were rediscovered by Western science in the late nineteenth, and twentieth century (Jacobs, 2007). In 1896 the effects of Mescaline were published in the British Medical Journal (Jacobs, 2007), and from then until the 1960’s, extensive research was done on the use of psychedelic compounds. During this time synthetic chemists were manipulating molecules to create new compounds that were related to natural psychedelics, and at the same time freely sharing many of these compounds with their friends and colleagues, leading to much experimentation in fields as diverse as botany, anthropology, and the arts (Jacobs, 2007). Arguably the most important discovery of this time was Albert Hoffman’s discovery of the psychoactivity of LSD in 1943. Extensive research was done on multiple applications of LSD from 1943-1966 in the fields of medicine and psychiatry, as well as by the American military (Jacobs, 2007).

By the mid 1960s psychedelics had drastically increased in popularity, through the previously described distribution among academics and artists, and the regular use of psychedelics such as LSD became a central part of a growing countercultural movement. The hippie movement, in addition to its psychedelic cultural manifestation, also included a political ideology associated with pacifism, anarchy, and destabilizing the structural hierarchy of capitalist society. The strong association between psychedelics and the hippie movement, marked the beginning of a strongly political opposition to the use of psychedelics that spread culturally among politicians and individuals opposed to the political ideals of this group.

Despite a large body of positive evidence supporting multiple beneficial uses of psychedelic compounds, in 1966 LSD was made illegal to possess in the United States of America, and soon afterward the majority of psychedelic research ceased continuation. As the political culture of the United States changed severely at this same time, politicians and main stream media began to depict psychedelics as a dangerous threat to society, and as a result the majority of society developed an adverse association with the use of psychedelics (Jacobs, 2007). This perspective had lasting implications, and in 1976 the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances came into existence, a complex regulatory framework, outlawing the vast majority of psychedelic compounds.

Struggling against the oppression of this prohibition, some medical research still continued in the late twentieth century. Many scholars disputed the claims being made about the dangers of psychedelics as being unscientific and largely false, and some research continued, although it received great opposition resulting in a drastic decrease in funding. One such researcher was biochemist Alexander Shulgin, who developed a unique relationship with the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, who granted him a Schedule 1 research license, allowing him to synthesize and possess illegal psychedelic compounds (Wolfson, 2014). Shulgin’s prolific research career included the synthesis of hundreds of new psychedelic compounds, as well as the writing of two definitive books: Pihkal, and Tihkal, each of which outlines the chemistry, pharmacology, and experiential psychology of all known psychedelic Phenethylamines and Tryptamines. (Wolfson, 2014). These two books are considered the authoritative textbook of psychedelics amongst psychedelic scholars.

From the late 1980s to the present day however, some restrictions on psychedelic research have been lifted for specific research groups, and as a result we are currently in a time known as the Psychedelic Renaissance, wherein a gradual increase in research involving human participation has led to a wealth of substantial positive evidence for the use of psychedelics in humans, which is only beginning to be explored. Although the public opinion is still mixed toward the dangers of psychedelic research, changes in perception based on an increase in positive research has facilitated an ethical reevaluation for many individuals leading to an increase in support.

[/toggle]

The Neurological Effects of Psychedelic Compounds

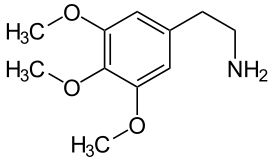

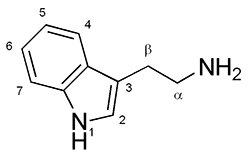

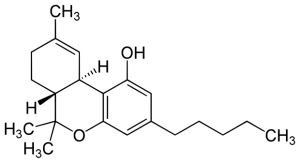

Psychedelic’s typically fall into two main chemical categories, Phenethylamines and Tryptamines, though there are also many psychedelic compounds which do not fall into either of these categories (Fantegrossi, 2008) . Below you will find descriptions of the neurological effects of these two categories of chemical compounds, as well as a description of the neurological effects of Cannabinoids, the psychoactive chemicals derived from marijuana, which do not fall into either of the above categories but do demonstrate psychedelic properties.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Phenethylamines

“]

Phenethylamines are organic alkaloids (plant based compound that has a physiological action on humans), derived from phenylalanine, and are structurally similar to many neurotransmitters and hormones, particularly serotonin (Fantegrossi, 2008). The most widely studied phenethylamine is the organic chemical mescaline, derived from the peyote cactus, and the majority of other psychoactive phenethylamines are mescaline derivatives synthesized in the lab. All psychedelic phenethylamines are a unique chemical variation of the same core structure (the mescaline molecule) (Fantegrossi, 2008).When introduced to the central nervous system, phenethylamines bind to various serotonin receptors, having the dual effect of activating the receptor while also rerouting the existing serotonin typically released to bind to that receptor. The result is a complex reorganization of brain function, leading to perceptual changes in consciousness, triggered by the activation of affected serotonin receptors. The phenethylamines have a particular affinity for the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors, and recent research has concluded that it is the interaction with these receptors that most likely produces the resultant psychedelic state (Fantegrossi, 2008). Phenethylamines tend to be highly potent, and standard doses can have a lasting effect from eight hours to more than one day. It is also worth noting that phenethylamines are also known for a rapid development of tolerance on repeated administration (Fantegrossi, 2008).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Tryptamines”]

Compared to Phenethylamines, there is a significantly larger list of psychedelic tryptamines. The most commonly used psychedelic tryptamines are N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), Psilocybin (“Magic” Mushroom), Bufotenin, and Ibogaine. Tryptamines are a monoamine acid, derived from the amino acid tryptophan via decarboxylation (Fantegrossi, 2008). The core structure of tryptamines is the double indole ring system with an aminoethyl at the 3-position (Fantegrossi, 2008). The biosynthesis of all tryptamines result from modification of the tryptophan structure, and many neurotransmitters, including serotonin, are such tryptamine derivatives (Fantegrossi, 2008).Psychedelic tryptamines are characterized by the modification of the four and five positions of the double indole ring of the basic tryptamine structure (Fantegrossi, 2008). When introduced to the central nervous system, psychedelic tryptamines bind to a variety of receptors, not limited only to serotonin receptors, however they are most notably effective in activating the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor (Fantegrossi, 2008). Similar to the function of phenethylamines, the complex activation of the affected receptors, leads to an alteration in brain function, producing the resultant psychedelic mental state.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Cannabinoids”]

Marijuana is a chemically complex psychoactive plant, with a long history of medicinal and recreational use in a wide variety of applications. To date, scientists have identified over 500 different chemical constituents in marijuana, contributing to the complexity and unique pharmacology of this plant (Beckley Foundation, 2017). The main psychoactive components of Marijuana are known as cannabinoids, with the dominant cannabinoid responsible for the psychedelic aspect of the effects of marijuana being delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (Beckley Foundation, 2017). Cannabinoids interact with the endocannabinoid system, consisting of two types of cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, found in the brain and the immune system (Beckley Foundation, 2017). THC primarily binds with the CB1 receptors in the brain, which typically interact with the neurotransmitter anandamide. Anandamide plays a role in the regulation of feeding behavior, motivation, and pleasure, and is not considered psychoactive, however THC remains bound to CB1 receptors longer than amandamine which is how they produce the resultant psychedelic effect.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Applications of Psychedelics to Music

Now that we have a basic understanding of psychedelic drugs, and the neuroscience behind their function, the remainder of this blog will outline some potential applications of psychedelics to the process of music making. Topics will include a variety of musical processes, including listening, the creative process of music making, as well as social and therapeutic aspects of combining psychedelics with music. Each topic will combine existing research in related fields to specific musical processes, in order to establish hypotheses about the potential benefits of introducing psychedelic research in the field of music.

[toggle title=”Music Perception” state=”closed”]

One of the hallmark features of psychedelics is their drastic alteration to cognitive perception. Of particular interest in the field of music is how psychedelics affect music perception, particularly in relation to listening. Below is a discussion of two areas of research where correlations between the neurological effects of certain psychedelic drugs and the perception of music have been established.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Cannabis Induced Hyperfocus on Musical Time-Space”]

Recent research at the UK based think tank the Beckley Foundation on the effects of cannabis on music perception suggests that the ingestion of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol leads to a hyperfocused state of listening as the result of an expanded perception of time, as well as an increased sensitivity to high frequency, amplitude, and acoustic space (Fachner, 2001). In an experiment involving individuals undergoing EEG brain scans while listening to music both before and after the administration of THC, Jorg Fachner discovered a significant increase of Alpha frequencies in the parietal cortex of participants listening under the influence of THC. This area of the brain is responsible for coordinating different perceptive fields between auditory responses in the temporal cortex, input from somato-sensoric areas of the brain, as well as selective attention processes (Fachner, 2001). Alpha frequencies are associated with a vigilant state of information processing, and are considered indicators of an efficient information processing strategy.

The experiential results of this experiment included increase in the subjective perception of time, an increase in perception of high frequencies, and increased sensitivity to intensity thresholds in amplitude (Fachner, 2001). The sum total of these effects lead to an overall temporary enhancement of acoustic perception as a result of hyperfocused attention on musical time-space (Fachner, 2001). Fachner concludes that this intensified receptive state explains the popular attraction of many musicians, particularly those associated with the early days of jazz music and those associated with the hippie movement of psychedelic music in the 1960s, to the use of Marijuana while engaging in musical activity (Fachner, 2001). Further he suggests that with an increased familiarity with this hyperfocused state, it may be of beneficial use to musicians in the act of performance in addition to listening (Fachner, 2001).

[/tab]

[tab title=”LSD and Music Induced Brain Imagery”]

Research in the fields of music therapy as well as neuroscience on the effects of LSD on music listening have demonstrated that psychedelics enhance many of the subjective aspects of music listening (Kaelen, 2016). In an experiment involving fMRI brain imaging on participants listening to music under the influence of LSD, Mendel Kaelen (Imperial College, London) discovered that participants listening to music under the influence of LSD demonstrated a modulation of connectivity between the Parahippocampal gyrus and the Visual Cortex (Kaelen, 2016). The experiential effect of this modulated connectivity in participants correlated to an increase in eyes closed visual imagery of a complex and autobiographical nature. Kaelen concludes that LSD works synergistically with Music in potentiating the therapeutic phenomena of music to evoke an emotional response as well as autobiographical memory. This synergy will be looked at in greater detail in the section about music therapy and healing below, however on a perceptive level this experience could have practical benefit for both a performing musician seeking a deeper personal or emotional connection to their repertoire, or to a listener interested in a personalized novel listening experience.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Creativity” state=”closed”]

Creativity is central to the process of music creation. The use of imagination and abstract thinking to achieve novel ideas in the production of an artistic work, is highly valued in assessing the relative merit of art. Recent research provides some evidence that psychedelics have the capacity to positively increase individual creativity. Further exploration of this correlation may be greatly beneficial to musicians, as well as all artists and scholars who value creativity in engaging in their particular field.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Schizotypy, Divergent Thinking, and Cannabis”]

Divergent thinking refers to the fluency and flexibility with which the working memory creates new representations (Schafer, 2012). This type of thought process is an essential part of what we conceptualize as creativity, and often brings out novel ideas and solutions to open ended questions. It is without question that this type of thought process is highly valued by musicians as part of their creative process, from composition and improvisation, to interpreting a work or listening with “fresh ears”.

Schizotypy is a term used in cognitive psychology to define a continuum of cognitive characteristics and experiences ranging from mild dissassocociative states to more extreme cases of psychosis. It is interesting to note that while extreme levels of schizotypy are associated with mental illnesses such as psychosis and schizophrenia, many studies have shown a link between higher levels of creativity and higher levels of schizotypy in individuals (Schafer, 2012). Research has also linked increased levels of shizotypy with cannabis use(Schafer, 2012). Although this link is often used to highlight the dangerous relationship between cannabis use and individuals who are at a high risk of developing psychosis, Gráinne Schafer has conducted research that extends this link into a correlation between cannabis use and increased creativity (Schafer, 2012). Participants completed multiple tests used to measure levels of schizotypy and its associated effect on divergent thinking (a trait associated with creativity) on separate occasions where they did not and subsequently did smoke marijuana. The results indicated an increase in divergent thinking, congruent with an increase in Schizotypy, while under the influence of Marijuana, for both participants who were considered to have high levels and low levels of creativity prior to the experiment (Schafer, 2012). More specifically, Schafer concludes that the neurological explanation for the increase in divergent thinking while under the influence of marijuana is due to a disinhibition of frontal cortical functions (Schafer, 2012). While this research supports a positive link between increased creativity and cannabis use, it should also highlight the danger of cannabis use for those individuals who are at a higher risk of developing psychosis.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Creativity and the Phenomenology of the Psychedelic Experience”]

Many famous scholars, artists, and musicians have cited their experience of psychedelic use as having a positive effect on significant breakthroughs and problem solving due to an increase in creative thought. In his research on DMT Benny Shannon, a cognitive psychologist at The Hebrew University in Jerusalelaem, has drawn a correlation between the ingestion of Ayahuasca, a traditional beverage containing the tryptamine DMT, and an increase in creative capacity due to the multifarious phenomenological effects of DMT that lead to an induction of enhanced imagination (Shannon, 2000). The phenomenological effects of DMT demonstrated by the research of Shannon include hallucinatory effects in perceptual modalities, psychological insight, intellectual ideation, spiritual uplifting, and mystical experiences.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Music and Psychedelics in Therapy and Healing” state=”closed”]

Modern research has provided a wealth of evidence supporting the psycho-therapeutic value of psychedelics, in studying their administration within the context of both psychiatry as well as socio-cultural ritual healing ceremonies. This final section will look at the synergistic therapeutic value of combining music and psychedelics in the context of both clinical use in music therapy as well as traditional use in tribal healing rituals.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Ritual use of Psychedelics and Music in Tribal Healing Ceremonies”]

For thousands of years many tribal societies have combined music and psychedelics into ritual healing ceremonies. In recent years many scholars have investigated these rituals in order to discover the relationship between music and psychedelics in the resultant effect of these healing ceremonies. Marlene Dobkin de Rios, a medical anthropologist and psychotherapist, has studied the role of hallucinogens and music in over a dozen tribal societies throughout North and South America. Through her research, she has drawn the conclusion that the most prominent role of music in psychedelic healing ceremonies, is to create a predetermined perceptive framework through which the participant is able to navigate within their altered state of consciousness during the drug induced state (Shannon, 2000). In this context, she uses the analogy of a children’s jungle gym, to describe the role of music in the psychedelic state(Shannon, 2000). Her argument is that the mathematical framework of the music functions like the interlinked bars of a jungle gym, to provide a space for exploration of the conscious experience of the psychedelic state. Further, she believes that the importance of music in these ceremonies is in providing the shamanic healer in charge or leading the ceremony the ability to manipulate the music in this way to guide participants toward a specific goal, such as a supernatural vision or the perceived communication with a spiritual diety (Shannon, 2000).

[/tab]

[tab title=”LSD and Music Therapy”]

Prior to the criminalization of LSD, many research studies in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy demonstrated positive results in the therapeutic benefits of the use of LSD in a therapeutic context. Many experiments in psychiatry that took place during this time demonstrated an increase in positive results when psychedelic psychotherapy was accompanied by music. The research of Bonny and Pahnke at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, outlines the following benefits in introducing music into psychedelic psychotherapy:

1. Helping the patient relinquish usual controls and enter more fully into his inner world of experience

2. By facilitating the release of intense emotionality

3. By contributing toward a peak experience

4. By providing continuity in an experience of timelessness

5. By directing and structuring the experience

(Bonny, 1972)

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[/toggle]

It is exciting to know that we are currently living in the time known by many researchers as the Psychedelic Renaissance. The wealth of psychedelic research being done by prominent scientists in a diverse range of fields, and the overwhelming amount of positive findings that have resulted, is collectively demonstrating the potential benefit further research on these compounds could have for humanity. As the positive findings increase, society at large is also beginning to change its previously held view points on these substances. As demonstrated in this blog, much of this research has already implicated a wealth of beneficial possibilities in the introduction of psychedelic research to the field of music. It is the authors hope that by reading this blog post, the general public will become more educated to these possibilities and hopefully this will lead to much needed further investigation.

[toggle title=”References” state=”closed”]

Aldridge, D., Fachner, J., and Schmid, W. (2006). Music, perception and altered states of consciousness. Music Therapy Today 7(1) 70-76.

Bonny, H. L., & Pahnke, W. N. (June 01, 1972). The Use of Music in Psychedelic (LSD) Psychotherapy. Journal of Music Therapy, 9, 2, 64-87.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Nutt, D., Leech, R., Hellyer, P. J., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., … Chialvo, D. R. (February 03, 2014). The entropic brain: A theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., Tyacke, R. J., … Nutt, D. J. (January 01, 2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 6, 2138-43.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Kaelen, M., Bolstridge, M., Williams, T. M., Williams, L. T., Underwood, R., Feilding, A., … Nutt, D. J. (January 01, 2016). The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Psychological Medicine, 46, 7, 1379-90.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Muthukumaraswamy, S., Roseman, L., Kaelen, M., Droog, W., Murphy, K., Tagliazucchi, E., … Nutt, D. J. (January 01, 2016). Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 17, 4853-8.

Fachner, J. (2002). Topographic EEG Changes Accompanying Cannabis-Induced Alteration of Music Perception— Cannabis as a Hearing Aid?. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics, 2(2), 3-36. Retrieved from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J175v02n02_02

Fachner, Jörg (2001). The Space Between the Notes—Research on Cannabis and Music Perception. 11th IASPM Conference, Day Two (Subjectivities and Identities). 308-319.

Fachner, J. (September 01, 2006). An Ethno-Methodological Approach to Cannabis and Music Perception, with EEG Brain Mapping in a Naturalistic Setting. Anthropology of Consciousness, 17, 2, 78-103.

Fantegrossi, W. E., Murnane, K. S., & Reissig, C. J. (January 01, 2008). The behavioral pharmacology of hallucinogens. Biochemical Pharmacology, 75, 1, 17-33.

Jacobs, A. The Medical History of Psychedelic Drugs. (2007). University of Cambridge. Retrieved from http://psychedelic.nfshost.com/history_of_psychedelics.pdf

Kaelen, M., Barrett, F. S., Roseman, L., Lorenz, R., Family, N., Bolstridge, M., Curran, H. V., … Carhart-Harris, R. L. (October 01, 2015). LSD enhances the emotional response to music. Psychopharmacology, 232, 19, 3607-3614.

Kaelen, M., Roseman, L., Kahan, J., Santos-Ribeiro, A., Orban, C., Lorenz, R., Barrett, F. S., … Williams, L. (January 01, 2016). LSD modulates music-induced imagery via changes in parahippocampal connectivity. European Neuropsychopharmacology : the Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 26, 7, 1099-1109.

Lebedev, A. V., Lovden, M., Lebedev, A. V., Rosenthal, G., Feilding, A., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (January 01, 2015). Finding the self by losing the self: Neural correlates of ego-dissolution under psilocybin. Human Brain Mapping, 36, 8, 3137-3153.

Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Moran, R. J., Brookes, M. J., Williams, T. M., Errtizoe, D., Sessa, B., … Nutt, D. J. (January 01, 2013). Broadband cortical desynchronization underlies the human psychedelic state. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 33, 38, 15171-83.

Rios, M. D., & Katz, F. (1975). Some Relationships between Music and Hallucinogenic Ritual. The “Jungle Gym” in Consciousness. Ethos, 3, 1, 64-76.

Schafer, G., Feilding, A., Morgan, C. J. A., Agathangelou, M., Freeman, T. P., & Valerie, C. H. (March 01, 2012). Investigating the interaction between schizotypy, divergent thinking and cannabis use. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 1, 292-298.

Shannon, B. (2000). Ayahuasca and Creativity. MAPS, 10(3), 18-19.

Stone, J. M., Morrison, P. D., Nottage, J., Bhattacharyya, S., Feilding, A., & McGuire, P. K. (August 01, 2010). Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Disruption of Time Perception and of Self-Timed Actions. Pharmacopsychiatry, 43, 6, 236-237.

Tagliazucchi, E., Carhart-Harris, R., Leech, R., Nutt, D., & Chialvo, D. R. (November 01, 2014). Enhanced repertoire of brain dynamical states during the psychedelic experience. Human Brain Mapping, 35, 11, 5442-5456.

Tagliazucchi, E. et. Al. (2016). Increased Global Functional Connectivity Correlates with LSD-Induced Ego Dissolution. Current Biology, 26(8), 1043–1050

Terhune, D. B., Luke, D. P., Kaelen, M., Bolstridge, M., Feilding, A., Nutt, D., Carhart-Harris, R., … Ward, J. (January 01, 2016). A placebo-controlled investigation of synaesthesia-like experiences under LSD. Neuropsychologia, 88, 28-34.

Turton, S., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (January 27, 2015). A Qualitative Report on the Subjective Experience of Intravenous Psilocybin Administered in an fMRI Environment. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 7, 2, 117-127.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Image Credits” state=”closed”]

Ian Levack, Study for Net of Being. (Painting by Alex Grey) Retrieved from:

www.flickr.com/photos/ianlevack/3706106038/in/album-72157621073687577/

Alan Rockefeller, Image #6514. (Psilocybin Mushrooms.) Retrieved from:

http://mushroomobserver.org/image/show_image/6514

Frank Vincentz, Lophophora Williamsii (Peyote Cactus.) Retrieved from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lophophora_williamsii_ies.jpg

Erik Fenderson, LSD Blotter Retrieved from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/LSD#/media/File:LSD_blotter.jpg

JonRHanna, Shulgin sasha 2011 hanna jon. Retrieved from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shulgin_sasha_2011_hanna_jon.jpg

NEUROtiker, Structure of Mescaline. Retrieved from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Phenethylamine_alkaloids#/media/File:Mescalin_-_Mescaline.svg

Tryptamine Structure. Retrieved from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tryptamine_structure.png

Yikrazuul, Tetrahydrocannabinol. Retrieved from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetrahydrocannabinol#/media/File:Tetrahydrocannabinol.svg

Kent Schimke, Jan082015lma1b (Fractal Pattern.) Retrieved from:

www.flickr.com/photos/22603020@N04/16275567211/in/photolist-qNdx6M-iU5u8k-oyGdPY-p7xVAf-ef4KcL-qiVTgX-aqNWyV-dLuNfQ-op1Dg3-ifdfii-e69TcD-qBozhn-qiNQEY-dSHcdw-ef4Kq5-ohhr2P-p7fxNH-dLuMNG-cA9GTf-ehrp4D-oQ2FoR-oyM8Wt-oQ2FZR-s9zTfA-dLpgg8-oyKhLd-ehx9bY-e8spVv-uBLHsB-ekhWDq-pDBiy4-di2Rpf-oMK9yf-7GJz94-i4u89T-ehx91S-ekcfvp-e8KqZF-qy6oao-p7tXKq-kd7PtL-eeY1sk-kd69oc-eeXZXM-qTPeSn-qL5LwN-pp1wCy-qTJLBf-nipECG-dLuNAW

bob marley, la marihuana es algo. Retrieved from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_mejor_cosaaa.jpg

Edward S. Curtis, Hamatsa Ritualist, 1914. Retrieved from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamatsa#/media/File:Hamatsa_shaman2.jpg

[/toggle]

Simply wish to say your article is as surprising. The clearness in your post is simply cool and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission allow me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the rewarding work.

Howdy! This article could not be written much better!

Reading through this article reminds me of my previous roommate!

He constantly kept talking about this. I am going to send

this post to him. Fairly certain he will have a great read.

Many thanks for sharing!

This is my first time go to see at here and i am really pleassant to read all at single

place.

I am extremely impressed along with your writing abilities

as neatly as with the structure in your blog. Is that this a paid subject or did you modify it yourself?

Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to look

a great blog like this one today..

Excellent article. I absolutely appreciate this site.

Keep writing!