Your recital is getting dangerously closer, and a question haunts your nights: How will I be able to memorize all this music?

Why, oh, why, do we perform from memory???

Well, you can blame Franz Lizst for that (Service, 2024; Watson, 2009).

Performing from memory was rare before the mid-19th century because composers thought it did not put their work forward and made it too much about entertainment. The virtuoso Liszt (1811-1886) decided to impress his audience by leaving the scores at home, but one – quite important! – thing to know is that he only played from memory his own repertoire, and only even a part of it, so he could make something up if anything went wrong (Service, 2024).

The trend created by Liszt is still alive today and some musicians are even making playing from memory their signature move. An example would be the Aurora Orchestra rehearsing Shostakovich’s Ninth Symphony from memory: (https://youtu.be/NmSTANQalP8)

You remember that your next recital has to be memorized? How did watching this video affect your stress level?

Although playing from memory can be an anxiety-inducing activity (Hallam, 1997) and having a memory slip is one of the biggest fears among musicians (Gonzalez & Sowby, 2020), there are also multiple advantages to playing from memory. For example, it allows you to focus more on the musical and expressive aspects of the performance by freeing your brain from the score, it can give you a better understanding of the piece and facilitate communication with the audience (Boucké, 2022; Chiu, 2020; Hallam, 1997; Watson, 2009).

To obtain these benefits, you must therefore start memorizing. But how?

Learning and memorizing: Two processes that go hand in hand

To get familiar with a new piece, you’ll probably get your hands on the score, listen to a few recordings, while looking at the score or not, and then play or sing it for the first time. That’s already great!

First step: Encoding

You’ve initiated the first step of learning, called encoding, by which the first trace of the piece is formed in your brain. In fact, each new piece of information you want to learn has to be encoded in such a way as to find its place in the brain.

Second step: Consolidation

By practicing the new piece, fixing mistakes, improving the technique involved, recognizing patterns… you are consolidating the neural pathways created in your brain, which means they are reorganized, stabilized, multiplied, and linked to previous knowledge.

Third step: Storage

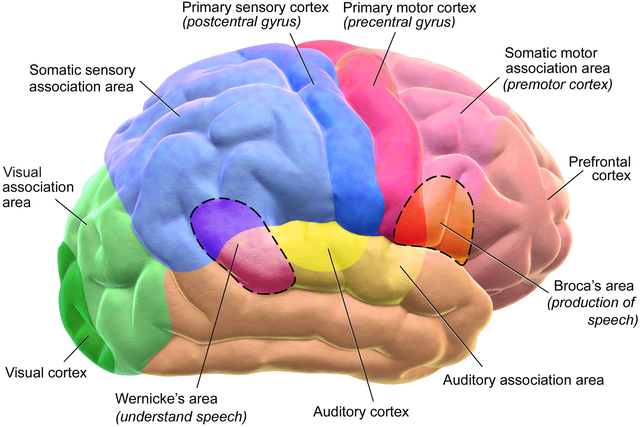

If you pay attention – you need to pay attention! –during the encoding and consolidation steps, information will then be stored securely in different areas the brain, its location depending on the type of input. For example, the memory of the score itself will be stored in the visual cortex, the memory of how it should sound like in the auditory cortex, the fingering in the motor cortex…

You’ve just started to learn the musical piece and memorization is already in full swing!

Memory

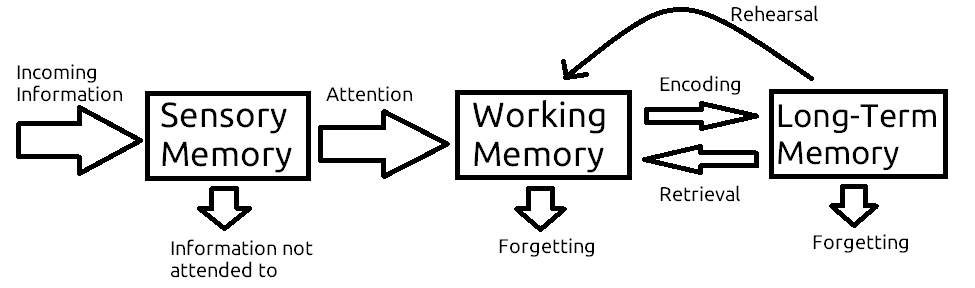

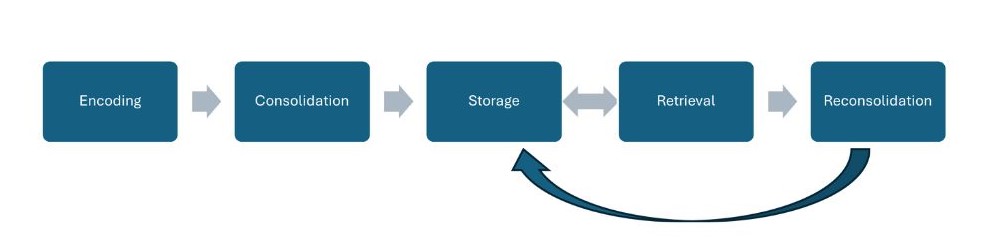

Indeed, each step of the learning process calls on the three categories of memory: sensory, short-term (working) and long-term. Let’s do an overview of the memorization process which is triggered by each new information that comes your way, as shown here:

Imagine you are in a practice room, working on a new piece : the walls are beige, the faint smell of the perfume of the person who was here before fills the air, you feel a mild pain in your lower back, you hear a saxophonist struggling with a scale on the other side of the corridor, you are trying to figure out how to sing a high note by squatting (yes, non-singers, we singers do that).

All your senses are involved, and sensory memory is activated. In less than a second, depending on the level of attention paid to an element, the brain decides if the information should be processed further.

During your practice session, the successful singing of the high note is more likely to be treated as relevant than the color of the walls and, therefore, to be transferred in the next category of memory, the short-term (or working) memory, that mainly uses the frontal area of the brain (Figure 4).

Long-term

Working memory can only hold seven items at once, including during performance, depending on the complexity of the stimuli (Boucké 2022, Svard, 2023). The information is kept for less than one minute, and then either forgotten or put into long-term memory (Svard, 2023), so it can be retrieved later. The hippocampus is the structure responsible for transferring information from short-term to long-term memory. It is involved in learning, memory and emotion. As shown on figure 5, it is located on both sides of the temporal lobe of the brain, right above your ears (Wendt, T., 2022).

Long-term

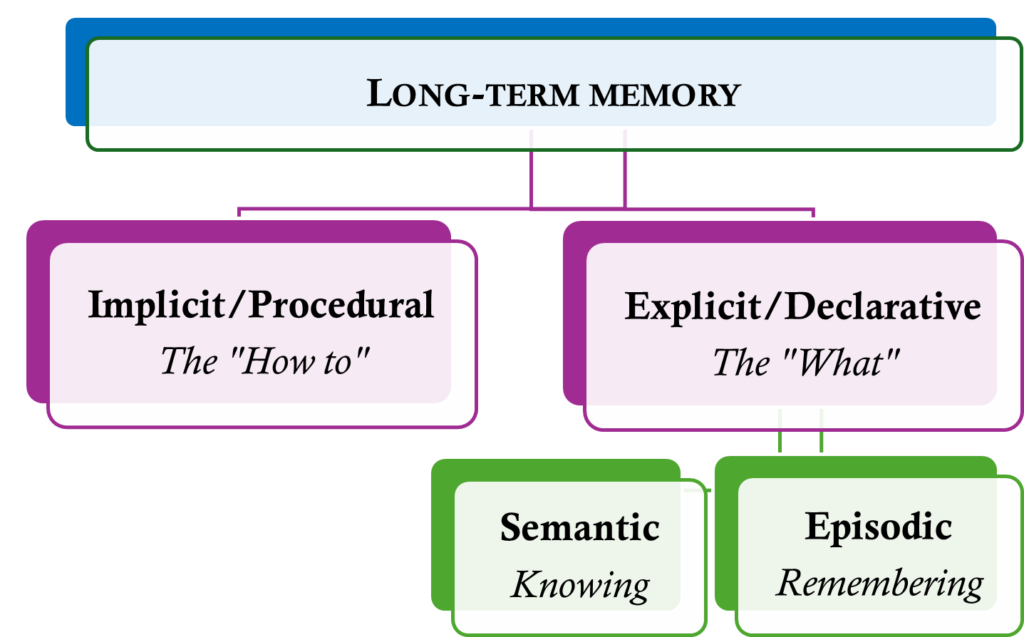

Long-term memory is subdivided this way:

The information stored in procedural, or implicit, memory is difficult to forget once learned, and it can be accessed without thinking about it consciously (Svard, 2023). Either in your practice room or during a performance, you are likely not worried about forgetting HOW to play your instrument or sing!…

The stress of having a memory slip comes mostly from the declarative, or explicit, memory. Its semantic branch is the most likely culprit, being the one that KNOWS facts, concepts and details (Svard 2023). You remember the name of the composer, the structure of the piece, a particular rhythm in one bar, you know the words and their meaning, where to move on stage during an opera… This kind of memory also allows you to transfer knowledge you’ve acquired working on one piece to another.

Episodic memory is the one by which you REMEMBER what you experienced in your life. You can recall the moment you received your first violin, the one time you sang in front of the Prime Minister… Episodic memory is the keeper of your personal history, which gives you a sense of self (Svard, 2023). The amygdala (figure 7), a structure located deeply in the brain, links the memory of an event to the emotions you felt when it happened, and the ones you feel remembering it. Events with strong emotional components create more durable, more vivid, and rich memories (Kensinger & Ford, 2020; Nineuil et al., 2020). So, if you get a standing ovation the day you play a new piece in a studio class, you’ll tend to remember the experience more strongly. There’s a good chance you’ll return to work on your piece with enthusiasm, thanks to the positive feelings attached to it by the amygdala.

Now that you’ve formed the memory of the piece, your aim is to be able to find it again when the need arises.

Fourth step: Retrieval

The process by which a learned information, or a memory, is brought back from long-term to working memory so it can be used at a given time is called retrieval. Either during practice or performance, the brain uses the pathways you created when you worked on the piece to restore its components.

Fifth step: Reconsolidation

And then, every time you access a memory, it changes. You never play a piece exactly the same each time, so every iteration is merged to the previous ones to form the most updated memory. As you get more confident with your playing, you might add rubato, put more emphasis on a word, change fingering… and these changes will become new semantic elements incorporated into the memory of the piece. The sense of pride in having played a difficult passage well, or the fear of getting caught up in rapid ornamentation, will also enrich the episodic context associated with the piece.

Here is a visual reminder of the 5 steps of learning:

This is all great but, is it possible to make performing from memory less stressful? Be happy, there are many tips available to help you deal with your memory challenges!

Let’s take a look at some of the tips that scholars recommend for strengthening the memory of your piece of music, organized here in the logical order in which they can be used in relation to the learning process.

Memorizing music: useful strategies

>>> Start holistically

Shawn Boucké, in his article ‘Efficient music memorization: Start with the whole’, states that the holistic method, which simply means playing the whole piece from the beginning to the end, should be employed early in the learning process and is the strongest starting point. The holistic method must however be used as part of a deliberate practice with the primary aim of memorization.

Deliberate practice : [is] highly structured with the attention focused

on improving a particular aspect of performance. […] requires

considerable effort and mental concentration (Eriksson, Krampe and

Tesch-Romer, 1993: In Watson, 2009, p.260).

This approach creates a complete image of the piece of music in the brain, as it becomes a long chain of information (Boucké, 2022).

>>> Diversify inputs

At the early stage of learning, it is helpful to work from the score, to listen to the piece, and to practice on your instrument because it creates ‘‘aural memories through hearing, visual memories through reading and kinesthetic memories through muscle movements’’(Boucké, 2022, p.35). This diversity of sources of information establishes connections and storage in different locations of the brain, which solidifies memory and facilitates retrieval (Boucké, 2022; Chiu, 2020).

>>> Learn words and music together

Learning a piece with words? By paying attention to them and linking them to the music, you will add pathways in language areas of the brain (Broca and Wernicke’s areas, see Figure 2: Motor and sensory regions of the cerebral cortex), which will enrich the information about the piece you store in memory.

If you are a singer and need to memorize the words as well, research (Ginsborg, 2002) suggests that working on words and music together from the start is more helpful than targeting them separately. Memorizing a song goes faster and is more accurate when the widest variety of these strategies are used: accompanying yourself while singing, counting, counting from memory, playing the melody, singing the words, singing the words from memory, speaking the words.

>>> Chunk and practice by segments

Here is where musicianship and music theory classes really pay off! Indeed, your musical knowledge plays a big role in efficient memorization. It enables you to understand the structure of a piece and to recognize patterns and groups (scales, arpeggios, chord progression…) which facilitates chunking.

Chunking : Grouping together a series of [items] that are then

remembered as a unit (Watson, p.257)

Given that working memory can only contain seven items, chunking allows you to retrieve and work with longer bits of the piece rather than individual notes (Boucké, 2022).

After playing holistically through the piece, it is important to do segmented practice – use your chunks! – to make your memorization more secure and give you various landmarks or starting points in case something goes awry. Having worked on the piece as a whole will later help connecting each section because a phrase will be triggered by the previous one (Boucké, 2022).

>>> Map the piece

Understanding the structure will also allow you to map the piece (González-Miller & Sowby, 2020). You can map the whole structure, the harmonic progressions, the expressive and interpretative cues, the text… You can also hierarchize the chunks in a graph (Watson, 2009). You can visit the website ‘the memory map for music’ (https://www.memorymapformusic.org/), made by two university level music teachers, Melissa Colgin Abeln and Rebecca Payne Shockley, to view examples of mapping. This technique creates a new visual input, adding to the knowledge about the piece stored in declarative memory.

>>> Sleep on it

Sleep has a huge impact on your ability to learn and remember. First, it allows encoding of new information to happen as a tired brain is not able to manage inputs efficiently. Second, in a stressful situation (like a performance!), the well-rested brain will retrieve stored information more easily (Svard, 2023). Third, research has shown extensively that consolidation happens during sleep by making the neural pathways created during the day stronger and more stable (Boucké, 2022, Svard, 2023). Both the declarative knowledge (the long German text you memorized for your Schubert’s piece) or procedural/motor (the new bowing the conductor asked the string section to use) are solidified by sleep. Even a nap can help (Debarnot et al., 2011)!

>>> Use mental practice or mental imagery

You can practice (and memorize) without making a sound! You may or may not be looking at the score while hearing the music in your mind, or imagining the movements required to play or sing.

Mental practice : refers to the ability to rehearse music in the mind

without any muscular movements or acoustic feedback (Iorio et al.,

2021, p.230)

During mental practice, the activity in the brain is similar to that during physical practice, except for somatosensory input (perception from the senses) that is totally or partly absent (Watson, 2009). So, whereas physical practice stores data in memory mainly through motor and auditory feedback, mental practice uses cognitive pathways. It is probably this diversification of the circuits used that makes memorization more solid when a musician uses a combination of physical and mental practice, compared with physical practice alone (Iorio et al., 2021).

Some methods even recommend creating a mental imagery of the piece before touching the instrument (Davidson-Kelly et al., 2015)! … Note that this kind of approach, which requires highly developed musicianship skills, is opposed to the idea of playing/singing the whole piece as early as possible in the learning process, as presented above.

>>> Test your retrieval

When the concert is getting closer, it is a good idea to make sure that the memory of the piece is secure by practicing your retrieval. You hopefully remember that retrieval means bringing information stored in long-term memory back into working memory and is a step that will be crucial during your performance. When you place yourself in a fictitious performance situation and play from memory, you benefit from the “testing-effect”. This kind of practice strengthens long-term retention of information and will be more effective than just reviewing the score (Telesco et al., 2021).

Boucké (2022) suggests different ways to practice your retrieval:

- Segmented: work on small sections of the piece independently.

- Serial: play the whole piece and start from the beginning every time a mistake is made.

- Additive: make sure retrieval is efficient for a section, then add the next one, and so on, until you can play the whole piece from memory.

>>> Change the routine

Memories are associated with the setting in which they occur, through episodic memory. It is therefore important to vary practice room and times to avoid linking the memory of the piece too strongly to a given context, which could lead to memory slips when changing setting. Even changing the angle of the chair on which you practice, or the lighting of the room, could be helpful. Practicing in the actual concert hall helps the retrieval greatly during the performance because the neural pathways for playing the piece in the given venue already exist (Boucké, 2022).

In conclusion, fellow performer, let’s face it: memorizing a musical recital can be a nerve-wracking adventure. But! If you now take a trip down memory lane to check how much you can remember from reading this blog, you could embark on your musical journey equipped with a variety of efficient memorization strategies, discover which ones work best for you, and leave (a part of the) stress in the dust when you conquer the stage!

dgdgd

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boucké, S. (2022). Efficient music memorization: Start with the whole. American String Teacher, 72(3), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031313221104081

Chiu, F. (2020). Practicing memorization : Score-writing techniques. American Music Teacher, 69(4), 34–37. https://www.proquest.com/openview/f77df40013a47e465d67ec9b151e2050/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=40811

Davidson-Kelly, K., Schaefer, R. S., Moran, N., & Overy, K. (2015). ‘‘Total inner memory’’: Deliberate uses of multimodal musical imagery during performance preparation. Psychomusicology : Music, Mind and Brain, 25(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000091

Debarnot, U., Castellani, E., Valenza G., Sebastiani, L., & Guillot, H. (2011). Daytime naps improve motor imagery learning. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience,11(4), 541–50. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-011-0052-z

Ginsborg, J. (2002). Classical singers learning and memorizing a new song: An observational study. Psychology of Music, 30(1), 58–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735602301007

González-Miller, D., & Sowby, C. (2020). Achieve a solid, reliable and successful memory. American Music Teacher, 69(4), 27–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27143098

Hallam, S. (1997). The development of memorization strategies in musicians: Implications for education. British Journal of Music Education, 14(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051700003466

Iorio, C., Brattico, E., Munk Larsen, F., Vuust, P., & Bonetti, L. (2022). The effect of mental practice on music memorization. Psychology of Music, 50(1), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735621995234

Kensinger, E. A., & Ford, J. H. (2020). Retrieval of emotional events from memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-051123

Nineuil, C., Dellacherie, D., & Samson, S. (2020). The impact of emotion on musical long-term memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02110

Service, T, & Johnson, S. (2024, January 19). History of memorizing music: The trend for binning scores and music stands on stage. Classical Music, BBC Music Magazine. https://www.classical-music.com/features/science-of-music/history-of-memorizing-music

Svard, L. (2023). Learning and memory : two sides of the same coin. The musical brain : What students, teachers, and performers need to know (pp. 80-97). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197584170.003.0005

Telesco, P., Karaca, M., Ewing, H., Gilbert, K., Lipitz, S., & Weinstein-Jones, J. (2021). Does retrieval practice enhance memorization of piano melodies? College Music Symposium, 61(2), 1–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48645695

Watson, A. H. D. (2009). The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury. Scarecrow Press.

Wendt, T. (2022, September, 1). Hippocampus: What to know, WebMD, https://www.webmd.com/brain/hippocampus-what-to-know

IMAGES

Figure 1: Stage fright by Victore Jeg, CC-BY 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/28405532@N02/2814951286

Figure 2: Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436., CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Memory Process by Erich Parker, CC-BY-SA-4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Memory_Process.png

Figure 4: Polygon data from BodyParts3D (2010). Frontal Lobe Animation, CC-BY-SA-2.1-jp, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frontal_lobe_animation.gif

Figure 5: Anatomography, Life Science Databases (LSDB). Hippocampus small, CC-BY-SA-2.1-jp, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hippocampus_small.gif

Figure 6: Graph by C. Yergeau, based on Svard, 2023 (chapter 5)

Figure 7: Anatomography, Life Science Databases (LSDB). Amygdala small, CC-BY-SA-2.1-jp, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amygdala_small.gif

Figure 8: Graph by C. Yergeau, based on Svard, 2023 (chapter 5)