Have you ever experienced Music Performance Anxiety?

Performing can be a physically and mentally demanding activity and most musicians experience music performance anxiety (MPA) that can either negatively or positively impact their quality of performance. MPA is the “cognitive, behavioral, physiological components of anxiety felt before, during, and after performing” (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022, p. 206). When we experience anxiety, it triggers the body’s stress response.

What happens in the body when I feel MPA?

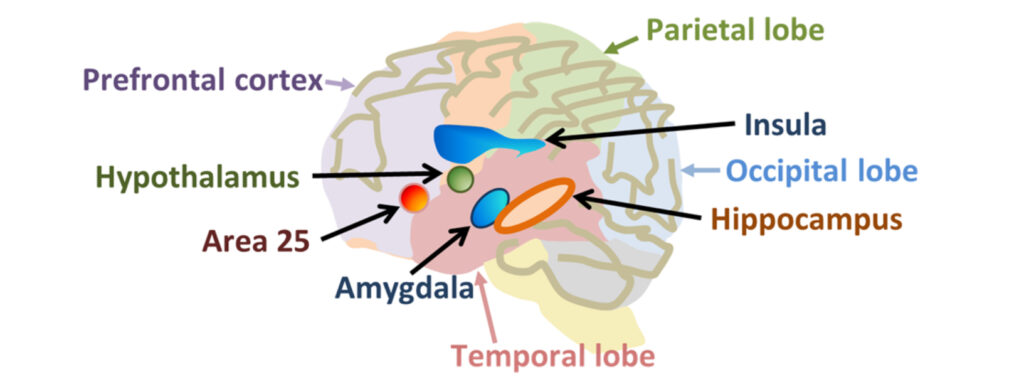

When the amygdala detects threat, it sends signals to the hypothalamus. This activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the adrenal glands which secrete hormones called adrenaline, also called epinephrine, into the bloodstream (Understanding the stress response, 2024). This produces physiological symptoms such as an increase in heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, muscle tension and dry mouth (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022). Followed by the initial detection of threat, another stress response system called the HPA axis (hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis) activates. The main function of the HPA axis is to release corticotropin releasing hormones (CRH) which triggers the relapse of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The ACTH triggers the release of the hormone cortisol which keeps the body alert and still under stress. As the threat goes away, the parasympathetic nervous system comes to play and relaxes the body (Understanding the stress response, 2024).

The video below from 00:10:40 to 00:11:50 summarizes the body’s stress response.

Alongside the physiological symptoms that occur, it can also produce psychological and behavioral symptoms such as low self-efficacy and avoidance behaviors (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022).

Anxiety can cause prolonged stress response…How does that change the brain?

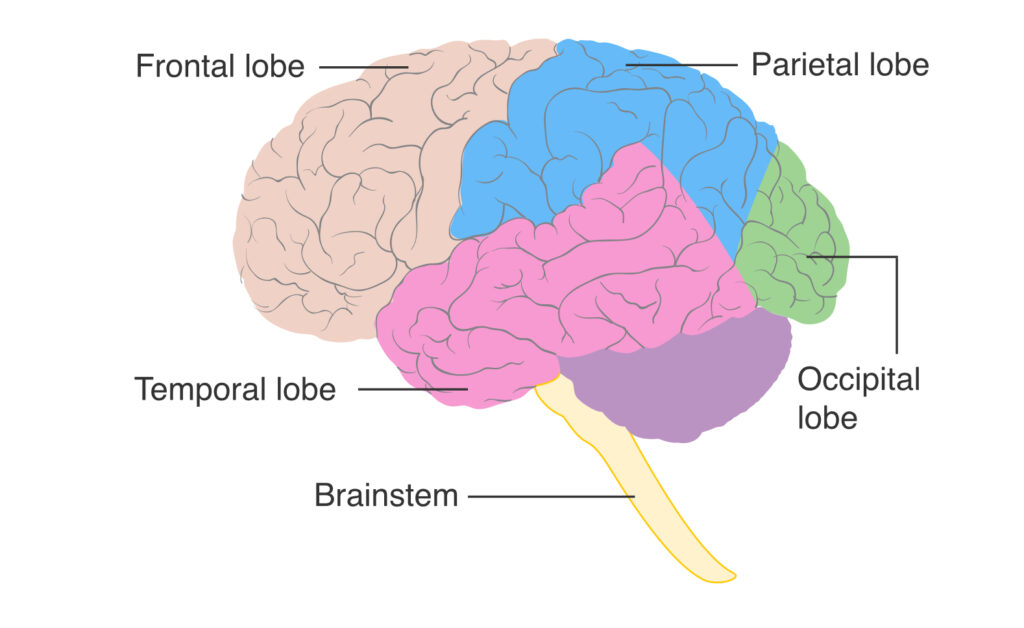

Research has shown that anxiety can change structures of the brain which can impact certain cognitive functions. Let’s start off by briefly looking at the main brain areas.

The brain is divided into 4 lobes: frontal lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe and the occipital lobe (Lobes of the brain, n.d). Anxiety can change the brain by affecting the prefrontal cortex (located at the front of the frontal lobe), parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and the insular cortex (Jeanne et. al., 2023).

Let’s now go through the functions of each area. I will also talk how changes to these structures impact their normal functions by presenting a study that relates to each area of the brain and music.

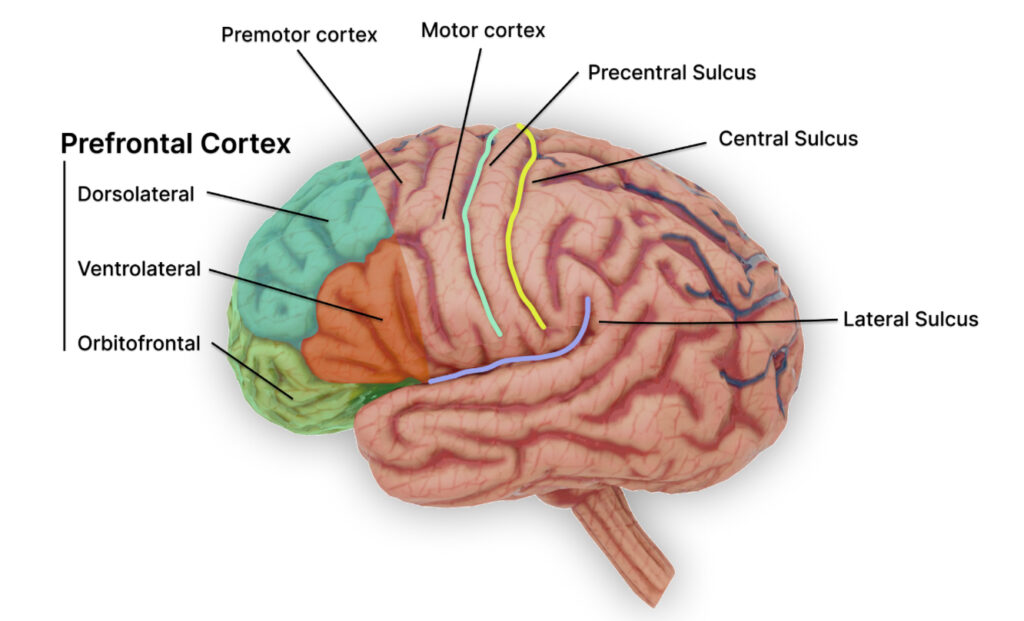

Prefrontal cortex

Located within the frontal lobe and is responsible for making executive functions which include planning, decision making, intentional actions and thoughts (Jeanne et. al., 2023).

Study

Background: Music is structured to form expectations, such as an anticipation of a C major chord at the end of a C major piece, which can inform a performer what actions to take, such as fingerings for certain chords. Deviating from the expectation and playing harmonically irregular chords can violate standard finger configuration which takes high level structural planning and re-planning (Bianca et. al., 2022).

Aim: To see how the structural and motor networks converge in the lateral prefrontal cortex and how these are then translated into physical movements like fingerings.

Participants: 26 individuals who had at least 6 years of piano training.

Method: Looked at fMRI scans while participants looked at pictures of 26 different 5 chord sequences. They were told to imitate these chords using the same fingerings. The chord sequences were repeated with 3 kinds of manipulation variants to test both structural and motor planning.

Result: Found that the structural and motor networks converge in the lateral prefrontal cortex, highlighting its role in turning musical concepts into physical actions. For example, fingering violation activated the frontoparietal while structural violation (for example unexpected chord sequences) activated the frontotemporal network. The lateral prefrontal cortex is part of both these networks (Bianca et. al., 2022). Thus changes to this area can affect musicians with task such as planning out fingerings.

Parietal lobe

Responsible for sensory processing and integration, spatial attention and awareness. It is also responsible for rapid information processing and attention (Jeanne et. al., 2023).

Study

Background: Reading music can induce parietal lobe activation and enhance visuospatial awareness (Patston et. al., 2007).

Aim: To see if musicians were better at paying attention and reacting to stimuli.

Participants: 20 musicians and 20 non-musicians.

Method: A line was flashed on a computer screen followed by a dot. Participants were asked to respond which side of the dot the line appeared.

Result: Musicians have better visuospatial awareness and they had quicker reaction times (Patston et. al., 2007). They require rapid attentional shift such as looking at the score and their hand so changes to this area can affect the ability to do this.

Temporal lobe

Involved in emotion processing and regulation, memory formation, language, auditory processing and music recognition (Jeanne et. al., 2023).

Study

Background: The anterior medial temporal lobe mainly includes the amygdala and the hippocampus which are both important for emotion processing (Khalfa et. al., 2008).

Aim: To look at the role of the anteromedial temporal lobes in music perception and recognition. The study assessed two emotional determinants: arousal and valence.

Participants: 26 epileptic and 60 healthy individuals. The epileptic patients had undergone a unilateral cortectomy, which is a surgical procedure that involves removing part of the cortex. In this case, the anteromedial temporal resection included the temporal pole, amygdala, entorhinal, perirhinal, part of the hippocampus, parahippocampus gyrus and superior temporal gyrus.

Method: Participants listened to 40 musical excerpts and after each excerpt, rated if the music was happy or sad as well as the valence and arousal levels.

Result: Individuals with right and left anteromedial resection showed a deficit in emotion recognition. For example patients with left anteromedial resection were not able to recognize sad music (Khalfa et. al., 2008). This shows that the temporal lobe is vital for processing auditory information which allows musicians to recognize the emotional meaning of the music. Changes to this area can also make it harder for musicians to express the emotion of a piece to the audience.

Insular cortex

Hub for evaluating, experiencing and expressing internal sensation (Jeanne et. al., 2023).

Study

Background: Empathy helps us understand other’s feelings and is based on shared brain representation that connect how we perceive and perform actions. Since dancing and music activities include lots of sensorimotor process related to action execution and observation, the study hypothesized that art training can enhance insular subnetwork function and result in greater empathic abilities. They specifically looked at the insula because that is the area in the brain that combines interoceptive and exteroceptive sensory information to create emotion and feelings (Gujing et. al., 2019).

Aim: To see how dancing and music training can enhance insular subnetwork and how that has an impact on empathic ability.

Participants: 21 dancers, 20 musicians and 24 control individual.

Method: Used rs-fMRI to scan their brain.

Result: Dancers and musicians showed stronger insular connectivity (Gujing et. al., 2019). Empathic ability is important for musicians in situations like chamber music where understanding each other’s emotion helps with communicating and responding to musical ideas, which creates a shared musical narrative. Thus changes to this area can cause a disconnect with other people and ultimately a less expressive performance.

Conclusion

Anxiety can change and affect the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe, temporal lobe and insular cortex (Jeanne et. al., 2023). The 4 studies presented all show that musicians use these areas. Musicians use the prefrontal cortex for planning out their physical movement (Bianca et. al., 2022). They use the parietal lobe for attentional shift (Patston et. al., 2007). Temporal lobe is used for emotional analysis of a piece (Khalfa et. al., 2008). Lastly, the insular cortex is used for empathic abilities (Gujing et. al., 2019). Thereby showing that changes to these areas can affect their normal function and prevent musicians from proper musical practice.

Learning how to effectively manage and deal with music performance anxiety can prevent negative side effects such as changes in brain areas from occurring. So… how do we manage music performance anxiety?

Treatments or coping mechanisms?

There are several ways of approaching and dealing with music performance anxiety, including treatments and coping mechanisms. In this blog, I will refer to ‘treatment’ as a medical care that is given and prescribed by healthcare providers. ‘Coping mechanism’ on the other hand, refers to the strategies or behaviors people do to help them manage their symptoms.

Let’s start off by discussing some of the treatment types.

1. Cognitive therapy

This therapy focuses on changing negative thought patterns into a more positive one. If you ever find yourself saying “I must not make a mistake” before performances, this can lead to unwanted tension and distractions. Thus cognitive therapy restructures the way we think and reassess the outcome (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022).

2. Behavior therapy

Have you ever avoided certain performances because you were scared? Music Performance Anxiety can create avoidance behaviors and behavior therapy targets this area. It reduces the fight or flight response by using progressive muscle relaxation through mental imagery, such as imagining yourself perform to gradually confront the fear of performance situations (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022).

3. Cognitive-behavior therapy

This therapy is the combination of the cognitive and behavior therapy mentioned above and most MPA treatment involves a combination of both. For example, it can involve cognitive restructuring, such as changing negative thoughts, combined with cue-controlled relaxation, such as muscle relaxation techniques. This treatment is said to be the most effective, but it does not address the aetiological factors (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022).

4. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

This therapy focuses on mindfulness and accepting the present distress rather than trying to eliminate it. Techniques include acceptance, mindful awareness and behavioral strategies (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022).

5. Beta blockers

Beta blockers are prescription-only medication (meaning consult with your physician as there are contraindications!) and work at blocking the effect of adrenaline on heart rate and blood pressure. This can alleviate physical symptoms such as hand tremor, sweaty palms, heart pounding. The most common type of beta blocker taken among musicians is propranolol, also called inderal (Patston, 2014). Although beta blockers can be effective for controlling physiological reactions, it does not alter your psychological reaction to stress and nervousness. While some may find this helpful, others may find that the adrenaline rush they experience before a performance is helpful for peak performance. There are also side effects that come with this medication including worsening of asthma, allergic reactions, gastrointestinal issues and nausea (Patston, 2014).

Coping mechanisms

Do you have any pre-performance rituals? Having a pre-performance ritual can be a good coping mechanism as it can help you to have a relaxed and focused performance.

One of the most common pre-performance routine is the centering approach taught by Don Greene (Kageyama, 2009). The centering approach goes as follows (you can try it now!):

- Pick a focal point – such as a door, water bottle or anything in front.

- Set clear intentions

- Know your goals and what you intend to do. For example, you could tell yourself I’m going to start the piece on the string with full hair.

- Close the eyes and breathe

- Breathe slowly to activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Scan entire body and release excess tension

- Release the tension through your entire body while breathing.

- Find the center

- Find your balance point and where you feel grounded.

- Remember intentions from step 2

- Direct the energy

- Feel where in your body you have the most energy accumulated through the previous steps. It could be in your feet, stomach. And direct the energy up your body, through your spine, to your head and shoot this energy out through your eyes (Kageyama, 2009).

Another practice approach is slow breathing which help reduce the contribution of the SNS and HPA axis. Dampening the SNS prevents the secretion of adrenaline and dampening the HPA axis prevents the secretion of cortisol which are both hormones that keep the body under stress mode (Osborne & Kirsner, 2002). You can try this out too!

- Breath in for 3 seconds

- Out for 3 seconds while saying “relax” at the same time (Osborne & Kirsner, 2022).

What can be done moving forwards? What can music schools do to raise awareness and provide help for students struggling with MPA?

According to statistics, 1/3 musicians suffer from MPA (Papageorgi, 2021). Moreover, between 15 and 70% of adult orchestral and choral musicians experience MPA (Papageorgi, 2021). While you can experience MPA at any age, adolescents may experience high levels of MPA which can be due to external stress (Papageorgi, 2021). Papageorgi (2021) found that out of 410 adolescent musicians, 11% reported high levels of MPA. Furthermore, a study reported that 10% of adolescent musicians reported that their musical career was negatively affected by MPA (Papageorgi, 2021). These statistics show that music performance anxiety is a common problem that is experienced by many musicians and has negative effects. Because it is such a widespread problem, it is important to be aware of it and have the tools to cope with it, especially for adolescents. It is equally important for mentors and schools to be able to provide the support and tools for young musicians to cope with Music Performance Anxiety. Here are some ideas on what music schools and mentors could do to alleviate some of the issues around MPA:

- Partnering with psychologists or therapists to offer professional guidance and help.

- Making it a required general education class, especially for incoming first years as they have less experience and tend to seek external validation.

- Creating an environment that reduces stigma around it by encouraging an open discussion for students to express their feeling and create a supportive environment.

- Integrating MPA into the syllabus for a class to raise awareness and have workshops or lectures on managing anxiety (Huawei & Jenatabadi, 2024).

- Social support, including encouragements from teachers can greatly impact a student’s self-esteem and confidence level. Thus teachers can be aware of giving constructive feedbacks and encouraging positive self-talks.

- Offering additional training for teachers and mentors about MPA so that they can better support their students.

- Implementing interactive activities such as breathing exercises before ensemble rehearsals and coachings to engage and encourage students to have pre-performance rituals and reduce MPA.

- Implementing MPA coping strategies into lessons and incorporate strategic activities such as simulated performances (Mazzarolo et. al., 2023).

Further resources

Interested in reading more about MPA? Below are a list of books on MPA as well as videos on performance anxiety from the perspective of a performer.

- Performance Anxiety: A Workbook for Actors, Singers, Dancers, and Anyone Else Who Performs in Public, by Eric Maisel

- The Musician’s Way: A guide to Practice, Performance, and Wellness, by Gerald Klickstein

- The Psychology of Music Performance Anxiety, by Dianna Kenney

- Performance Success, by Don Greene

- Music performance anxiety: New insights from young musicians, by Kenny and Osborne

References

Augustin Hadelich. (2022, August 29). Ask Augustin 50 – Dealing with performance anxiety. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-G_C5iFcsnM

Bianco, R., Novembre, G., Ringer, H., Kohler, N., Keller, P. E., Villringer, A., & Sammler, D. (2022). Lateral prefrontal cortex is a hub for music production from structural rules to movements. Cerebral Cortex, 32(18), 3878-3895. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab454

Cancer Research UK. (2014). Diagram showing the lobes of the brain CRUK 308. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/3756dbda-11d1-4bc7-ae58-5b1a37ba1c41?q=Lobes+of+the+brain&p=4

Gujing, L., Hui, H., Xin, L., Lirong, Z., Yutong, Y., Guofeng, Y., Jing, L., Shulin, Z., Lei, Y., Cheng, L., & Dezhong, Y. (2019). Increased insular connectivity and enhanced empathic ability associated with dance/music training. Neural plasticity, (1), 9693109. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9693109

Huawei, Z., & Jenatabadi, H. S. (2024). Effects of social support on music performance anxiety among university music students: Chain mediation of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1389681

Harvard Health Publishing Harvard Medical School (2024). Understanding the stress response. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response

Jeanne, M., Carson, F., & Toledo, F. (2023). Neuroanatomical correlates of anxiety disorders and their implications in manifestations of cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Psych, 6(1), 34-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010003

Kageyama, Noa. (2009, July 23). How to make performance anxiety an asset instead of a liability. Bulletproof musician. https://bulletproofmusician.com/how-to-make-performance-anxiety-an-asset-instead-of-a-liability/

Khalfa, S., Guye, M., Peretz, I., Chapon, F., Girard, N., Chauvel, P., & Liégeois-Chauvel, C. (2008). Evidence of lateralized anteromedial temporal structures involvement in musical emotion processing. Neuropsychologia, 46(10), 2485-2493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.04.009

Mazzarolo, I., Burwell, K., & Schubert, E. (2023). Teachers’ approaches to music performance anxiety management: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1205150

Otosakanum2. (2025). PFC anatomy. [Photograph]. Openverse. https://openverse.org/image/59288d60-e275-472e-89e9-65b98ed3dbda?q=Prefrontal+cortex&p=45

Osborne, M., & Kirsner, J. (2022). Music performance anxiety. In McPherson, G. E. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance, (pp. 204–231). Oxford Academic. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190058869.013.11

Patston, T., & Loughlan, T. (2014). Playing with performance: The use and abuse of beta-blockers in the performing arts. Victorian Journal of Music Education, (1), 3-10.

Patston, L. L. M., Hogg, S. L., & Tippett, L. J. (2007). Attention in musicians is more bilateral than in non-musicians. Laterality, 12(3), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500701251981

Papageorgi, I. (2021). Typologies of adolescent musicians and experiences of performance anxiety among instrumental learners. Frontiers in psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645993

Professor Dave Explains. (2020, January 22). The physiology of emotion and stress. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zUafO9dJYlY

TEDxTalks. (2021, October 19). Overcoming performance anxiety through mental training I Miho Ohki I TEDxUniHalle. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdLlDUeSAmg

tonebase Guitar. (2021, September 18). Dealing with performance anxiety I Bill Kanengiser interview. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sd32QkcNhxQ

University of Central Florida. (n.d.). Lobes of the brain. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-parts-of-the-brain/