Do you experience discomfort during or after practicing? Has the thought of practicing become associated with pain? Do you feel that you may not be realizing your musical and interpretive ideas with as much physical ease, expressivity, and control as you would like?

Research has shown that a high percentage of musicians feel pain while practicing and playing their instrument (Clemente et al., 2014). Symptoms associated with pain can often be early signs of debilitating and emotionally devastating musculoskeletal injuries. The high level of proficiency and artistry required to achieve a successful professional career as a musician necessitate extensive and demanding hours of daily practicing. A variety of factors are frequently thought to cause playing-related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMDs) or act as contributors to discomfort in pianists: genetics, stress and anxiety, the pressure of a challenging career, compromising technique (Lederman, 2003). Many of these risk factors can perhaps be linked to one source – the way we practice. Research suggests that an increasing awareness and understanding of one’s physical self throughout daily preparation is key to preventing musculoskeletal injury (Foxman & Burgel, 2006; Shan & Visentin, 2010; Storm, 2006). By learning to be efficient and organized, practicing may become more effective and remain artistically rewarding and healthy.

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”What are PRMDs?” state=”closed”]

Due to the nature and intensity of their daily preparation, musicians often complain of pain and discomfort. For pianists, the origin of pain is most often located in muscles and ligaments of the neck, shoulders, arms, and hands (Lederman, 2003). As the pain becomes more serious and increasingly debilitating, these injuries – frequently referred to as prompted by “overuse” – may be diagnosed as a playing-related musculoskeletal disorder – PRMD. Triggered by an overload on the musculoskeletal system, these injuries are caused by “cumulative microtrauma to the muscle and connective tissue and are characterized by a gradual increase in pain and functional impairment” (Watkins, 1999, p. 313).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”What causes PRMDs in pianists?”]

Research has documented a myriad of risk factors specific to PRMDs in pianists. These include posture, technique, practicing schedule, physical habits, muscular conditioning, as well as hypermobility in the joints (Bragge, Bialocerkowski, & McMeeken, 2006). Much of the literature underlines one prevalent risk factor in particular – practicing routine and habits. [/toggle]

[toggle title=”Why might practicing be the culprit?”]

Playing the piano involves the complex coordination of the musculoskeletal system and the nervous system. It requires the precise control of small and large motions, tremendous dexterity and agility, speed, balance, and a high number of repetitive movements, all of which demand a great degree of accuracy. Pianists sometimes focus so intensely on the minute details required of the fingers that they forget a key ingredient to maintaining physical health and comfort- engaging the whole body while practicing and performing. As Thomas Mark (2003, p. 3) so aptly describes in his valuable resource, What Every Pianist Needs to Know About the Body: “We play the piano just as we run: by complex coordinated movement of our whole bodies”. An understanding and awareness of the musculoskeletal system will enable pianists to approach their instrument and their preparation in a healthy, comfortable, efficient, and effective way.

[blockquote author=”Thomas Mark (2003, p. 3)”]Saying that we play the piano with our fingers is like saying that we run with our feet. The fingers move when we play the piano and they are the only parts of our upper body that touch the piano. Similarly, our feet move when we run and are the only parts that touch the ground. But a runner who tried to improve his running by keeping his legs motionless and doing foot exercises would be ridiculous. He is similar to a pianist who keeps his arms motionless and exercises his fingers, although what the pianist does has the sanction of tradition. We play the piano just as we run: by complex coordinated movement of our whole bodies.[/blockquote]

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Physical awareness as we practice

Is there such thing as “perfect” technique? This can be a divisive question among teachers, however, in my opinion there is no “one size fits all” method to playing the piano. Rather, a successful and healthy approach to the instrument considers the complexity of anatomy and each individual’s unique characteristics. An understanding of the basic principles of anatomy and function will allow for comfort, efficiency, and effectiveness as well as longevity throughout one’s career as performer and educator. Greater awareness of the physical aspects of piano playing is key not only to injury prevention but can also enhance and increase one’s interpretive and expressive possibilities. According to Thomas Mark (2003), the following components are central to a fully engaged approach to the piano:

[tabs]

[tab title=”The spine”]

The spine supports and delivers the body’s weight during sitting. The front of the spine functions as the support mechanism while the back portion where the ribs attach, houses the spinal cord. Spinal imbalance (back-oriented sitting) posture will result in tension through the torso and arm muscles as they work to compensate.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Posture while sitting”]

There is a reason why so much time is spent on posture in early piano lessons. Healthy and even weight distribution maintains a center of gravity over the hip joints and sit bones (ischium) rather than thrown back towards the rear of the spine posture. Poor seated posture will increase pressure on the spine, which may result in tension and pain in the shoulders, arms, and back and thus impinge upon ease of movement.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Engaging our whole body”]

Transferring weight downward through the sit bones in order to maintain stability and balance is necessary to retain extensive mobility while in a seated posture. The size of the keyboard demands agility, flexibility, and stable movement. And of course, the legs are needed not only for pedaling, but also for continuous support and equilibrium.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Understanding muscles”]

While the smaller muscles located in the arms and hands – known as fast-twitch – enable incredible dexterity and agility, these do tire much more quickly and will become tense if engaged unnecessarily and overused. Being mindful of the larger, slow-twitch muscles (shoulders, back, and legs) and allowing these to initiate the smaller motions while playing will provide the stamina and strength necessary to maintaining health and being able to practice productively. The article “Promoting a Healthy Keyboard Technique,” underlines this concept stating that “injury often occurs as a result of underuse of the larger available muscles and overuse of the smaller muscles… the pianist who thinks of playing as originating in the fingers and working backwards is more at risk of overusing the smaller muscles” (Brown, 2000, p. 562).

[/tab]

[tab title=”The back”]

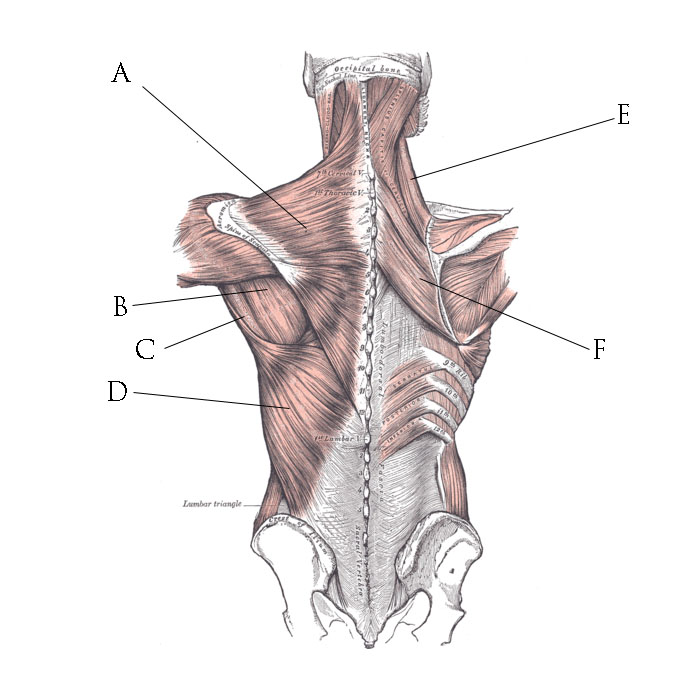

Muscles in the back consist of complex layers which attach to the shoulder blades, collarbone, as well as parts of the arm. This explains why tension in the back can impact any number of things: shoulder movement, arm mobility, hand flexibility. Encouraging pianists to think of the physical process of playing the piano as originating in the back and shoulder area will help in making full use of these larger muscles and result in the power, strength, and endurance required to play effectively.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Neck and head”]

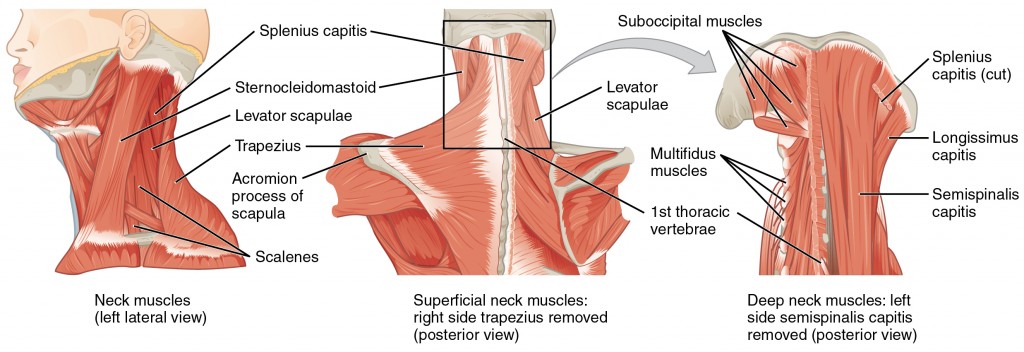

It is useful to be aware that the nerves to the arms originate in the neck area. Chronic tension in the neck can affect the whole body as it may restrict the mobility of the arms and hands. Avoid a head-forward posture and try to keep head placement as neutral as possible.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Quality vs. quantity

Musicians repeatedly deal with the misconception that the amount of time spent in a practice room reflects their dedication as artists, motivating them to spend countless hours at their instrument on a daily basis. However, research has shown that a greater amount of hours does not necessarily produce the expected result (Shan & Visentin, 2010). Certainly professional preparation requires disciplined, regular practicing, however, perhaps a more creative and varied approach will provide the ability to maintain the physical and mental strength needed not only throughout practicing but also in developing successful and rewarding performances.

Organization and practicing

As highly creative and imaginative individuals, musicians may be less inclined to consider the more pragmatic side of their craft at times. Planning and organizing practice sessions will help to establish more efficient practice schedules as well as support a more balanced preparation, increasing its effectiveness while continuing to enable artistic growth and reward.

Shan and Visentin (2010) propose that when it comes to practicing and the risk of injury, mere movements are not the problem, but rather the amount of time spent doing the movements. Musicians are often convinced that practicing repeated motions for long periods of time will lead to the artistic benefits being pursued. However, these two researchers from the field of performing arts health and wellness, propose that a practice schedule which sets time limits by considering the technical and artistic demands of each specific task, is a much healthier and more effective way of organizing one’s time. Furthermore, organizing practice sessions along these guidelines will also allow musicians to cultivate greater awareness of the physical and mental demands required throughout practicing, thus being able to make adjustments and modifications as needed, an essential component to injury prevention. Shan and Visentin (2010, p. 41) conclude: “thoughtful work may enable longer and more intense practice regimes, whereas poor practices may lead to the contrary and accelerate the development of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders”.

Take breaks!

Comparisons are often made between athletes and musicians; both careers demand incredible physiological and psychological strength, coordination, agility, and stamina. Foxman and Burgel’s (2006, p. 310) research suggests “music students often spend more hours practicing than athletes yet forego conditioning and rest intervals”. They advise taking breaks of 10-15 minutes every 60 minutes while practicing and including a warm-up routine before beginning (p. 313). This brings two valuable points to attention- that of interspersing practice sessions with sufficient, short breaks so as to give one’s body time to recover, as well as the idea of overall conditioning.

Injury prevention outside of the practice room

[tabs]

[tab title=”Overall conditioning”]

Fundamental to general health, the endurance, mental stamina, as well as strength and flexibility gained through regular exercise are all vital components to maintaining a healthy and successful performing career. Additionally, exercise plays a natural role in reducing tension- an essential ingredient to injury prevention (Wilke, Preibus, Biallas, & Frobose, 2011).[/tab]

[tab title=”Stretching and strengthening”]

Many musicians have found Pilates or Yoga very beneficial to countering the numerous hours spent practicing and performing. Health and wellness professionals have also effectively recommended other body posture work such as Alexander technique and the Feldenkrais method (Foxman & Burgel, 2006). Clemente et al. (2014) mention the need for further, more detailed research in this area as it relates to pianists; it has been documented they commonly deal with particular issues such as neck pain, yet more research is needed to determine specific exercises which would be particularly helpful to keeping the flexion and extension muscles of the neck healthy and pain-free.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Exercise”]

Wilke et al. (2011) recommend the type of exercise musicians engage in should be tailored to their playing-related requirements. For example, pianists might benefit especially from exercises related to upper-body strength as well as cardiovascular endurance. Compensatory strength training is also recommended so as to maintain symmetry and balance as well as assist in training those muscles not relied on as heavily.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[infobox color=”#91d367″ textcolor=”#ffffff”]

Healthy practicing guidelines

- Effective practicing is measured by thoughtful, aware, engaged work; going through the motions on auto-pilot is neither physically nor artistically beneficial

- Constant evaluation; listen, revise and reassess throughout each practice session

- Pacing – creating variation and contrast in one’s routine so as to employ a variety of muscles. Switching between sections within works, alternating or cycling through different pieces as well as sometimes simply altering the tempo will vary the required physical and mental demands.

- Mental practice – proven to be effective in combination with physical practice, it gives your body a chance to rest and recover!

- Avoid abrupt increases in practice times – increase sessions progressively

- Proper seating and posture! Chair height and adequate support are essential

- Consider lighting as well as the viewing angle of your music

- Staying alert and being productive includes sufficient hydration and proper nutrition[/infobox]

In conclusion

A variety of elements may play a contributing role to PRMDs in pianists, however, one’s practice routine is a factor that can be controlled and modified. As a result, its design may lay the foundation to injury prevention. With greater physical awareness, slight administrative adjustments, and increased thoughtfulness, pianists may gain the ability to more effectively realize their artistic goals and continue to strive towards the ultimate objective – compelling musical communication with audiences through expressive and meaningful performances.

[toggle title=”Useful online resources”]

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety: Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSDs)

Fitscript.com- Muscles and Activity

The Blog – The Bulletproof Musician

Does Mental Practicing Work? by Noa Kageyama, Ph.D

Make up your mind: Practice strategies by Mackenzie Stone

Warm-up sequence from The Cross-Eyed Pianist Blog

The benefits of good posture from TED-Ed by Murat Dalkilinc

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”References”]

Bragge, P., Bialocerkowski, A., & McMeeken, J. (2006). A systematic review of prevalence and risk factors associated with

playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in pianists. Occupational Medicine, 56 (1), 28-38. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqi177

Brown, S. (2000). Promoting a healthy keyboard technique. In R. Tubiana & P. Amadio (Eds.), Medical problems of the

instrumentalist musician (pp. 531-557). Malden, MA: Blackwell Science.

Clemente, M., Coimbra, D., Gabriel, J., Lourenco, S., Pinho, J.C., & Silva, A. (2014). Three-dimensional analysis of the cranio-

cervico-mandibular complex during piano performance. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 29 (3), 150-154.

Retrieved from https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/journalviewer.aspx?issue=1205&article=2058&action=1

Foxman, I., & Burgel, B. (2006). Musician health and safety: Preventing playing-related musculoskeletal disorders. AAOHN

Journal, 54 (7), 309-316. Retrieved from http://www.cmaj.ca/content/158/8/1019.full.pdf

Green, J., Champagne P., & Tubiana, R. (2000). Prevention. In R. Tubiana & P. Amadio (Eds.), Medical problems of the

instrumentalist musician (pp. 531-557). Malden, MA: Blackwell Science.

Lederman, R. J. (2003). Neuromuscular and musculoskeletal problems in instrumental musicians. Muscle & Nerve, 27(5),

549-561. doi:10.1002/mus.10380

Mark, T. (2003). What every pianist needs to know about the body. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, Inc.

Shan, G., & Visentin, P. (2010). A prisoner’s dilemma with asymmetrical payoffs: Revealing the challenges faced by performing

arts health and wellness practitioners. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 25 (1), 39-42. Retrieved from

https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/journalviewer.aspx?issue=1183&article=1819

Storm, S. (2006). Assessing the instrumentalist interface: Modifications, ergonomics and maintenance of play. Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 17(4), 893-903. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2006.08.003

Watkins, J. (1999). Structure and function of the musculoskeletal system. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Wilke, C., Priebus, J., Biallas, B., & Froböse, I. (2011). Motor activity as a way of preventing musculoskeletal problems in string

musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 26(1), 24–29. Retrieved from https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/

journalviewer.aspx?issue=1191&article=1891

[/toggle]

I think it is important to make this very obvious when a beginner is learning how to approach their instrument. I have found rather late that I was too tense and my technique was suffering. I found that the best performances I have had were where I have prepared in a relaxed state of mind that transferred to my body. This practice also helped me with stage anxiety. I was able to control my body so that I could play the way I wanted to.

Thoughtful and insightful summary, Kristen. I think this type of awareness will make a remarkable difference at any age; these are guidelines I have to remind myself of frequently still.

Magdalena