What is the best way to teach ear training? According to Edward E. Gordon, an educator and researcher in music education, the system used in schools is not the most efficient, and relies too much on technical and visual components, on music theory, and not enough on aural and listening components. Gordon argued that before the 19th century, most notably in the Renaissance and probably before, musicians practiced and were proficient with improvisation, a skill that relies on listening and imagining music. He also proposed a method to clearly define and make accessible the development of a good musical ear, a method that can be summarized in one word: audiation (Gordon, 2011).

Audiation is a term that was coined by Gordon in 1975. While doing studies on musical aptitudes, Gordon wanted to describe “[the] ability to hear and give meaning to music when sound is not physically present or may ever have been physically present” (Gordon, 2011). He argued that “audiation is to music what thought is to language” (Gordon, 1999). Like when we learn our native language, musical aptitude develops in four steps: listening to music, to build a “listening vocabulary”, then speaking (playing, singing), reading and finally writing music (Gordon, 1999).

Audiation is not in itself a new concept, and is taught and used by many musicians. Most probably, every professional musician uses it in one way or another. Pianists, such as Glenn Gould and Oscar Peterson, would often sing along with what they were playing. They appear to be imagining, and hearing music, which they transfer to their instrument. However, many musicians do not know how to describe and talk about this concept, let alone teach it. The question remains: Can audiation have an impact on the development of musical aptitude, and also on both technical skills and musical sensitivity?

Visualisation and athletes: A musical parallel

The process of visualisation that is used in audiation is very much akin to a technique that athletes use in their training, a technique described by researchers Ridderinkhof and colleagues as Kinesthetic Motor Imagery, or KMI for short. KMI is defined as “the cognitive ability that allows an individual to perform and experience motor actions in the mind, without actually executing such actions through the activation of muscles.” Studies show that 70% to 99% of elite athletes use KMI, and that they find the technique useful, valuable and enjoyable, when used in combination with physical training, to enhance the acquisition and refinement of fine motor skills (Ridderinkhof et al., 2015).

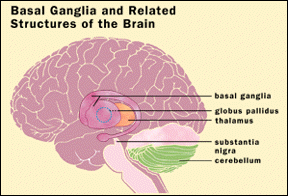

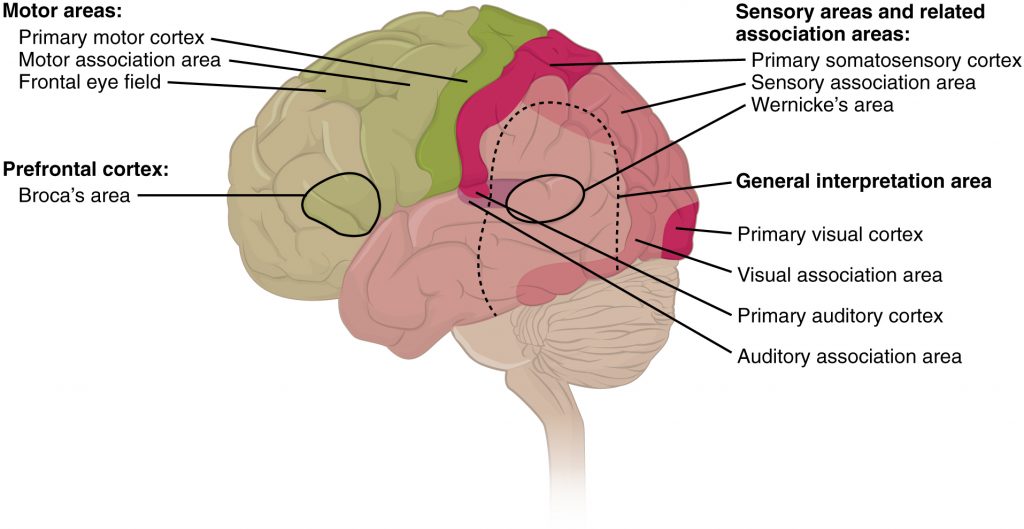

Studies also indicate that neural activity observed in overt (visible) physical activity is also mirrored in the cerebellum, motor cortex and basal ganglia when using KMI. However, it activates areas involved in the planning and preparation of an action, and not in the execution of the action itself. When performing an action, the brain creates a parallel between the action and the sensation of the action. Imagining that same action and its sensation has an impact on corticospinal excitability , which increases the brain and body’s potential for action.

Meanwhile, in the music research world, Brodsky and colleagues conducted experiments with musicians to determine if music notation produced aural mental image, if mental images produced during notational audiation engaged covert kinesthetic motions in the vocal folds, and engaged manual motor imagery. The goal was to see if musicians could also visualize how they would physically play on their instruments the music that they were hearing/audiating.

Both aural audiation and notational audiation were found to produce mental images, and engaged covert movements of the vocal folds. Even drummers, while reading percussion notation without pitches, engaged in the same covert kinesthetic motions in both the vocal folds and other parts of the body (arms, hands, legs…) (Brodsky et al., 2008).

Audiation’s potential for musicality

How do these researches link to the application of audiation? The work done on visualisation, with athletes and musicians, reinforce the idea that its effectiveness is not just theoretical, but based on fact. Mental practice is a great tool to develop and maintain skills related to the fine motor activities required when performing music. Its application goes beyond technical skills, because technique alone, for Gordon, is not enough to make a good musician. Audiation’s goal is to allow a musician to perform with sensitivity and expressivity. Music, and especially technique, needs to be put in context to give it meaning, much like individual sounds and syllables in a language start to make sense when they are ordered properly to create words and phrases (Gordon, 1999).

As previously mentioned, Gordon claimed that for audiation to be effective, one needs to first build a listening vocabulary, which necessitates listening to music, whether it be familiar or unfamiliar. If you ask jazz musicians how to learn a piece, they will often suggest to listen to recordings of the piece, and figure out on the instrument how to perform the music. By listening to different musical styles, one learns to differentiate shapes, melodic contours, and patterns, thus building a sort of auditory memory, or reference point, that Gordon calls a vocabulary. The following step is to try to “speak” the music, by imitating the sounds, or songs with the learned vocabulary acquired through listening. Once that is done, then the musician is ready to start learning how to read music, and consequently learn how to write it. Gordon emphasizes the idea that technique exercises, such as scales, need to come from the need to express music that was previously heard internally, otherwise one risks playing without really understanding what the music is about, and to play without musicality.

Approaching audiation: Building musicality and musical aptitude

Gordon defines music aptitude as “the potential to achieve music” (Gordon, 2003). It is not musical talent, or ability, or “gift”, as some people will say. Just Like there are different types of intelligence, there are also different types of music aptitude. Music aptitude is partly innate (we are born with it) and partly acquired. Like language, the development of music aptitude is best done at an early age, ideally before the age of seven (Bailey, 2012), but can still be taught later on.

To develop one’s audiation, one must be immersed in a musical environment. Gordon identifies three words in relation with the listening vocabulary:

[tabs]

[tab title=”Repetition”]

Listen to the same songs, chants, or pieces, several times, on several occasions, with the same parameters of tempo and key

[/tab]

[tab title=”Variety”]

Listen to music with various keys, modes, and meters.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Silence”]

Allow some time in silence to think, reflect upon and audiate the music in order to absorb it.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Practicing audiation

Gordon recommends that audiation first be taught without notation, as an aural-oral process (listening first, and then singing) and later on with notation, as an aural-oral-visual process (listening, singing and reading music) (Cross et al. ,2006).

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Without notation” state=”opened”]

- Start with short melodic patterns, scales, chords and rhythms. Listen to those patterns, audiate them, and attempt to replicate.

- Move on to short melodies, and repeat the same process (listen, audiate, sing)

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”With notation”]

- Provided with a starting note, audiate a specific musical item, like a scale, interval, or chord, and sing it back.

- Listen to that same musical item, and, with the help of a written starting pitch, (tonic or root) imagine how the complete musical item would be written.

- Again, sing the musical item.

- In a sight-reading book, choose a melody, and repeat the first steps:

- Imagine and sing the same musical elements previously worked on, this time in the key of the melody

- While looking at the starting pitch, listen to the musical item and imagine its notation

- Sing the musical item

- Finally, imagine the sound of the chosen melody, and sing it back.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Practical examples: how to apply the aural-oral-visual processes”]

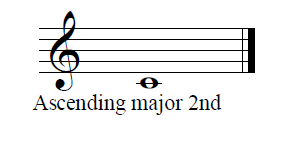

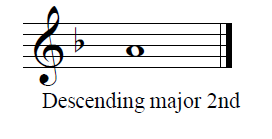

1. A practice of intervals: the major second (whole step)

– Using the provided pitch, take time and imagine an ascending major second.

– Using a vowel or syllable of your choice, attempt to sing it.

– Using the provided written pitch, listen to and imagine the notation of that ascending major second.

– Using solfege, or numbers, attempt to sing it.

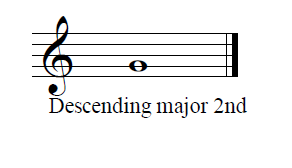

– Using the provided pitch, take time and imagine a descending major second.

– Now attempt to sing it.

– Using the provided written pitch, listen to and imagine the notation of that descending major second.

– Now attempt to sing it.

2.Major seconds in a melody

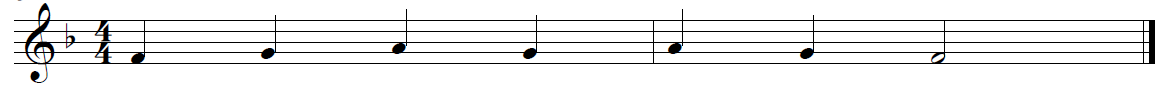

– Look at this short melody, in the key of F major.

– Using the provided pitch, take time and imagine an ascending major second.

– Now attempt to sing it.

– Using the provided written pitch, listen to and imagine the notation of an ascending major second.

– Now attempt to sing it.

– Using the provided pitch, take time and imagine a descending major second.

– Now attempt to sing it.

– Using the provided written pitch, listen to and imagine the notation of the descending major second

– Now attempt to sing it.

– Again, read this short melody.

– Take time and imagine the sound of the melody.

– Using the provided pitch, attempt to sing it through.

-Here is the full melody:

(Audio-visual material created by Félix Dupont-Foisy)

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

The aftermath of notational audiation

After the process of notational audiation, musicians are ready to listen to different pieces for their instrument, and attempt to sing the tunes. If they are able to sing the melody, they are ready to play it on the instrument. A similar process of learning music can also be found in methods such as Suzuki, Dalcroze, Kodaly and Orff. For more information on those methods, read chapter 1 of Frances Turnbull’s Learning with Music : Games and Activities for the Early Years. Technical choices, such as fingerings, will be guided by the music that was audiated, not by a mechanical standpoint. Furthermore, technical exercises and scales should be used in daily practice while applying the principle that audiation guides performance (First, imagine the sound of the scale, then play the scale). Physical motions should also be associated with a mental image of the pitch that is being played; to play the note that was audiated, the musician needs to do a certain action or movement with or on the instrument, and that action must be linked to a mental image. Imagining the note, how it would sound on the instrument and what gesture will create it, is what leads to an expressive performance (Cross et al.,2006).

Author: Félix Dupont-Foisy, 2018

[toggle title=”References”]

Articles:

Parr-Brownlie, L. C., Reynolds , J. N. J., & Rodgers, K. (2015). Basal ganglia, Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://academic-eb-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/levels/collegiate/article/basal-ganglia/624470

Bailey, J., & Penhune, V.B. (2012). A sensitive period for musical training: contributions of age of onset and cognitive abilities, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1252(1), 163-170. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06434.x

Brodsky, W., Kessler, Y., Rubinstein, B.-S., Ginsborg, J., & Henik, A. (2008). The mental representation of music notation: Notational audiation, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 34(2), 427-445. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1037/0096-1523.34.2.427

Cross, S., Hiatt, J. S. (2006). Teaching and using audiation in classroom instruction and applied lessons with advanced students, Music Educators Journal, 92 (5), 46 – 49. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.2307/3878502

Dalby, B. (1999). Teaching audiation in instrumental classes: An incremental approach allows teachers new to Gordon’s music learning theory to gradually introduce audiation-based instruction to their students, Music Educators Journal, 85 (6), 22 – 46. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.2307/3399517

van Elswijk, G., Schot, W.D., Stegeman, D.F. et al. (2008) Changes in corticospinal excitability and the direction of evoked movements during motor preparation: a TMS study, BMC Neuroscience, 9: 51. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-9-51

Garner, A. M. (2009). Singing and moving: Teaching strategies for audiation in children, Music Educators Journal, 95(4), 46 – 50. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1177/0027432109335550

Gordon, E. E. (1999). All about Audiation and Music Aptitudes: Edwin E. Gordon discusses using audiation and music aptitudes as teaching tools to allow students to reach their full music potential. Music Educators Journal, 86(2), 41-44. Retrieved from http://mcgill.worldcat.org/oclc/425441722

Gordon, E. E. (1979). Developmental Music Aptitude as Measured by the Primary Measures of Music Audiation, Psychology of Music, vol. 7, 1, 42-49. Retrieve from https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1177/030573567971005

Gordon, E. E. (2011). Roots of music learning theory and audiation, Chicago: GIA Publications. Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gordon_articles/1/.

Grashel, J. (1991). A Review of Selected Studies Using Gordon’s Audiation Theory. Update: Applications of Research, Music Education, Vol 10, Issue 1, 30 – 34. Retrieved from: https://doi org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1177/875512339101000107

Humphreys, J.T. (1986). Measurement, Prediction, and Training of Harmonic Audiation and Performance Skills, Journal of Research in Music Education, Vol 34, Issue 3, 192 – 199. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.2307/3344748

Liperote, K. A. (2006). Audiation for Beginning Instrumentalists: Listen, Speak, Read, Write, Music Educators Journal, Vol 93, Issue 1, 46 – 52. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1177/002743210609300123

Reynolds, A. M., Hyun K. (2004).Understanding Music Aptitude: Teachers’ Interpretations, Research Studies in Music Education, Vol 23, Issue 1, 18 – 31. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1177/1321103X040230010201

Ridderinkhof , K. R., Brass M. (2015). How Kinesthetic Motor Imagery works: A predictive-processing theory of visualization in sports and motor expertise, Journal of Physiology-Paris, Volume 109, Issues 1–3, 53-63. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphysparis.2015.02.003.

Books:

Gordon, E. E. (2003). Learning sequences in music: Skill, content, and patterns, Chicago:GIA Publications, Inc, 307

Hubbard, T.L. (2013) Auditory Aspects of Auditory Imagery. Lacey S., Lawson R. (eds). Multisensory Imagery. Springer, New York, NY, 51-76. Retrieved from: https://link-springer-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/book/10.1007%2F978-1-4614-5879-1

Partington, J. (1995). Learning and artistic preparation. Making Music, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 89-104. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/stable/j.ctt7zt186

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Media”]

Images:

OpenStax College (2013). Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/[CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1604_Types_of_Cortical_Areas-02.jpg

Henkel, John (July-August 1998). “Parkinson’s Disease: New Treatments Slow Onslaught of Symptoms”. FDA Consumer: p. 17. ISSN 0362-1332. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brain_structure.png

Videos:

Brown, R., Peterson, O., & Thigpen, E. (1964). C Jam Blues. Retrived from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTJhHn-TuDY

Additionnal material:

All pedagogical audio and visual material used in the “Practical example of aural-oral-visual process” section was created by the author of this blog, Félix Dupont-Foisy. You are allowed to reuse the material, so long as you credit the author.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Further readings”]

Turnbull, F. (2018). Where did music education start? Learning with Music: : Games and Activities for the Early Years. London: Routledge. Retrieved from : https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781317275343

[/toggle]

Leave a Reply