Hi! If you have been struggling with how to hold and play the viola with ease and in an efficient way, you’ve come to the right place.

As a violist myself, I’ve struggled with transitioning from the violin to the viola due to the different approaches to technique, but the aspect that has been hindering me the most is playing posture. Many teachers offer their own perspectives but I found that they all based their beliefs on one thing: to do what feels natural to you.

But what is “natural” exactly? If it’s been a habit of mine for several years, I’m sure it would train my body to feel that it’s natural too.

And so, I’ve embarked on this journey to explore the real meaning behind achieving the most natural posture that I can while playing my instrument, and my hopes are that you will find something that can benefit you as well. Let’s begin!

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”Can this also apply to violinists?” state=”closed”]

While there are significant differences in detail between technique for violists and violinists, the larger muscle groups which are engaged to support the instruments remain relatively similar (Turner-Stokes & Reid, 1999). For this reason, the postural suggestions which I am posting in this blog can be applied to violinists as well.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Before I explain the muscles which are used in each action, there are specific terms of anatomy which you should know.

These terms are used in the break-down below to describe the movements of each muscle.

[infobox color=”#81d742″] A rule of thumb when it comes to supporting your instrument in an optimal fashion (Kumar, 2008; Watson, 2009):

–use larger muscles (such as the trapezius) which are capable of supporting your instrument and movements for extended periods of time

–avoid relying on smaller muscles (such as the levator spinae) that easily fatigue [/infobox]

Now, here’s a break-down of which muscles in the upper extremity are used during several commonalities of viola posture:

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”Left shoulder raised ” state=”opened”]

trapezius and levator scapulae

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”muscle diagrams”]

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Left shoulder rotated inward” state=”opened”]

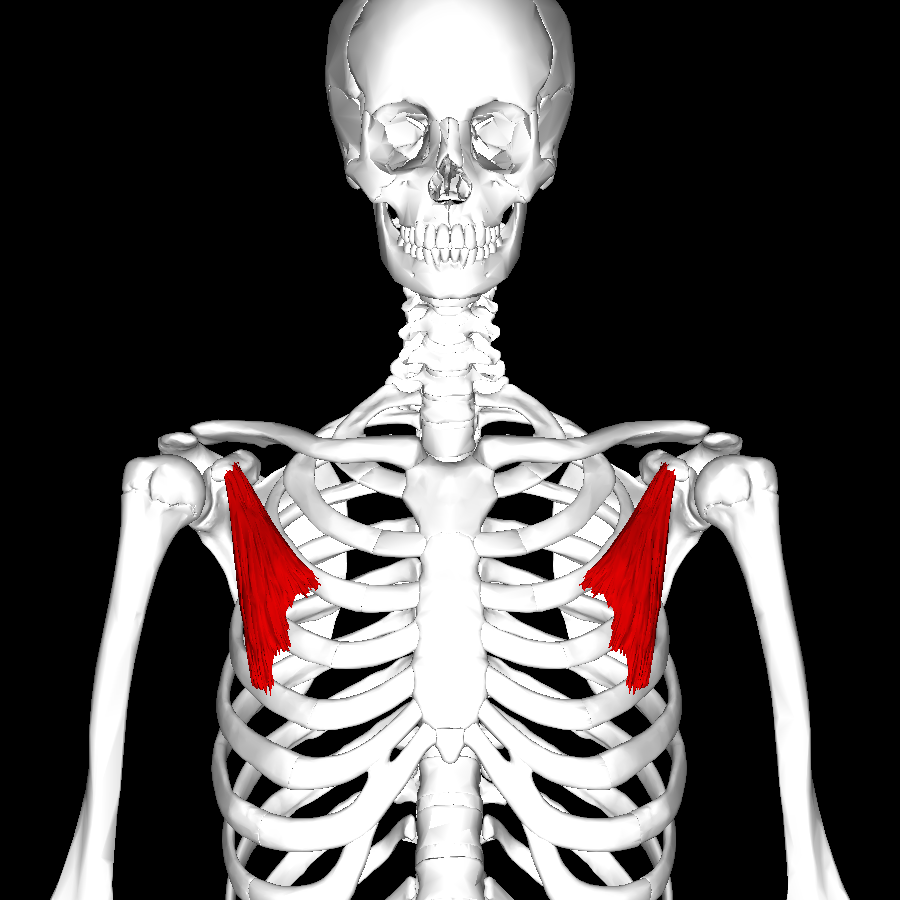

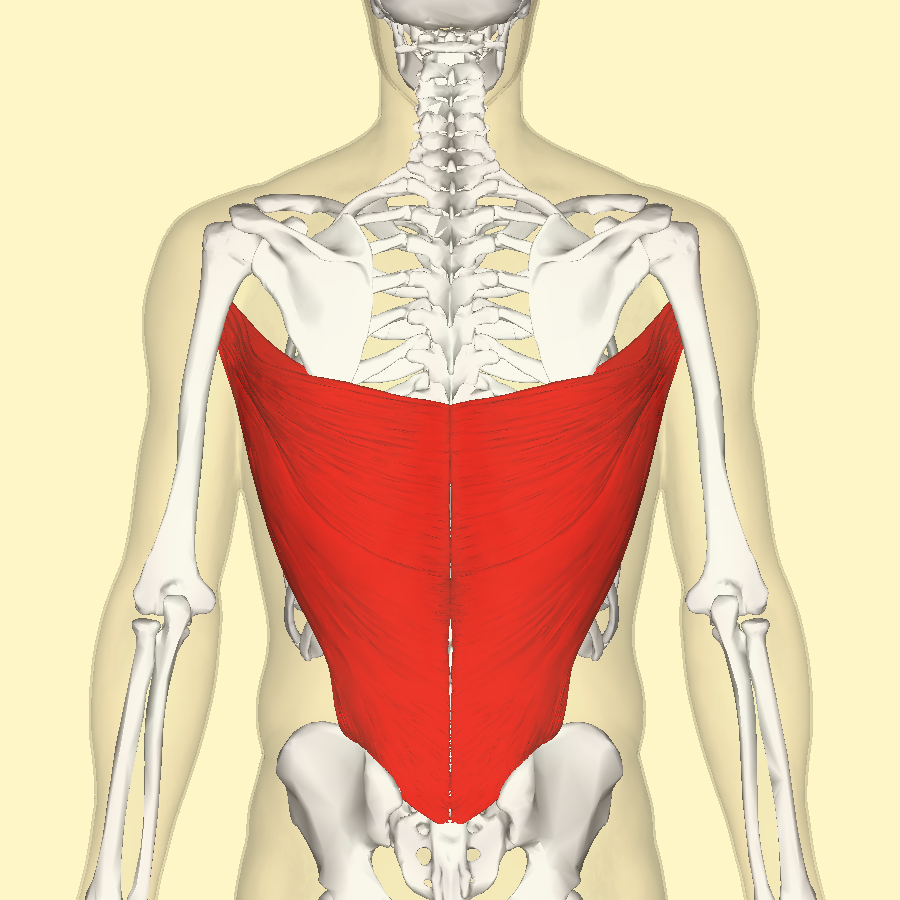

pectoralis minor, serratus anterior, rhomboids, levator scapulae, latissimus dorsi, and pectoralis major

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”muscle diagrams”]

Pectoralis minor  Serratus anterior

Serratus anterior Rhomboids

Rhomboids  Latissimus dorsi

Latissimus dorsi

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Left arm supporting instrument” state=”opened”]

Raising the arm: trapezius, levator scapulae and serratus anterior

Bearing loads on the shoulder: levator scapulae (also turns the neck to the side)

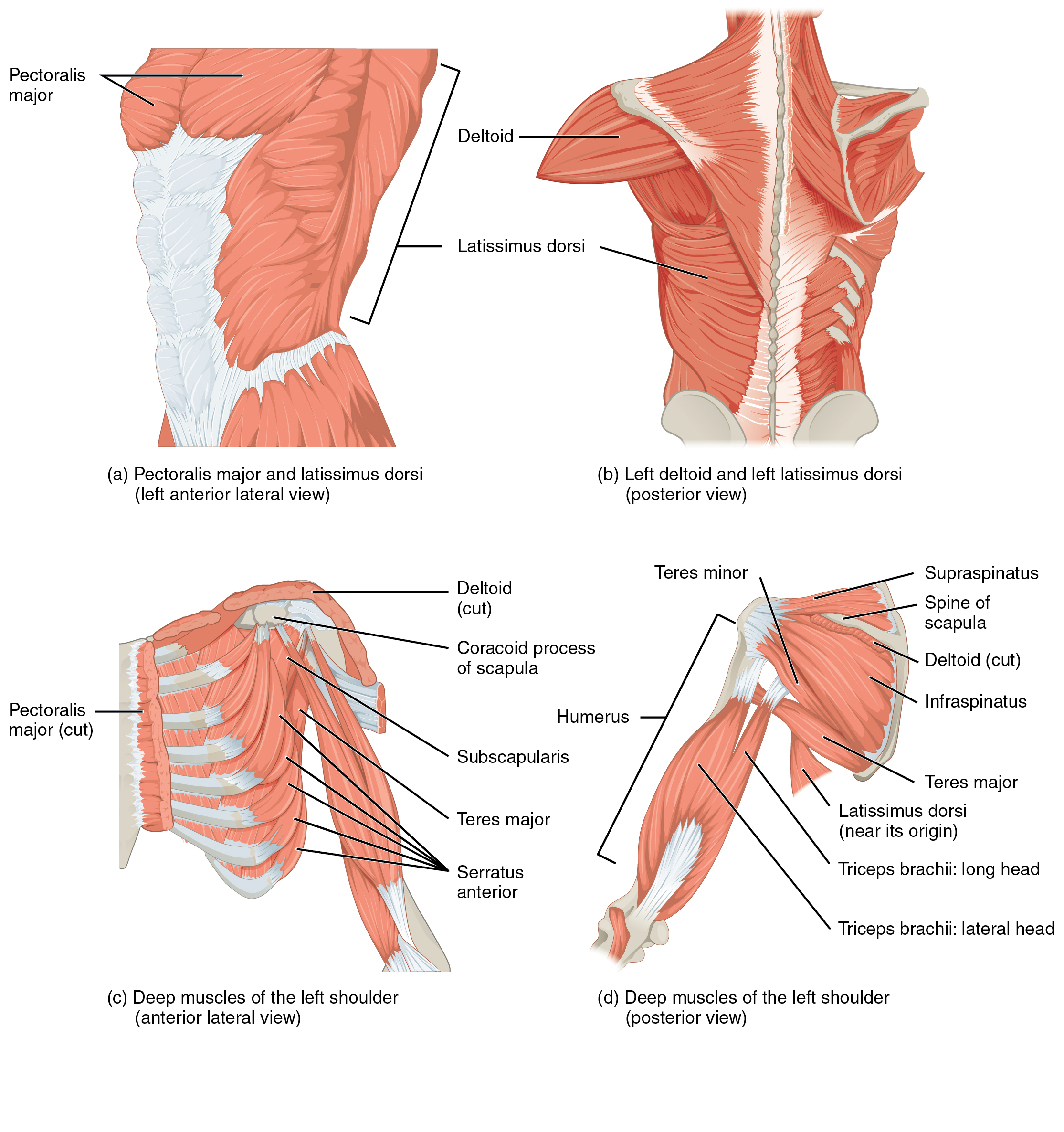

Bringing arm foward, flexing and medially rotating arm: pectoralis major, teres major, subscapularis, deltoid and coracobrachialis anterior fibers

Abducting arm: supraspinatus and deltoid’s intermediate portion

Supinating forearm, flexing elbow: biceps branchii, brachialis

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”muscle diagrams”]

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Right arm holding bow” state=”opened”]

Extending arm: deltoid posterior fibers, latissimus dorsi and teres major

Extending forearm: teres major, deltoid posterior fibers, coracobrachialis and triceps

Flexing arm: deltoid anterior fibers, pectoralis major, corachobrachialis and biceps

Flexing elbow: brachialis

Medially rotating humerus: deltoid anterior fibers, latissimus dorsi, teres major and subscapularis

Pronating forearm and hand: pronator teres and pronator quadratus

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”muscle diagrams”]

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

So you know the basics, now what?

What Happens When You’re Playing: In Detail

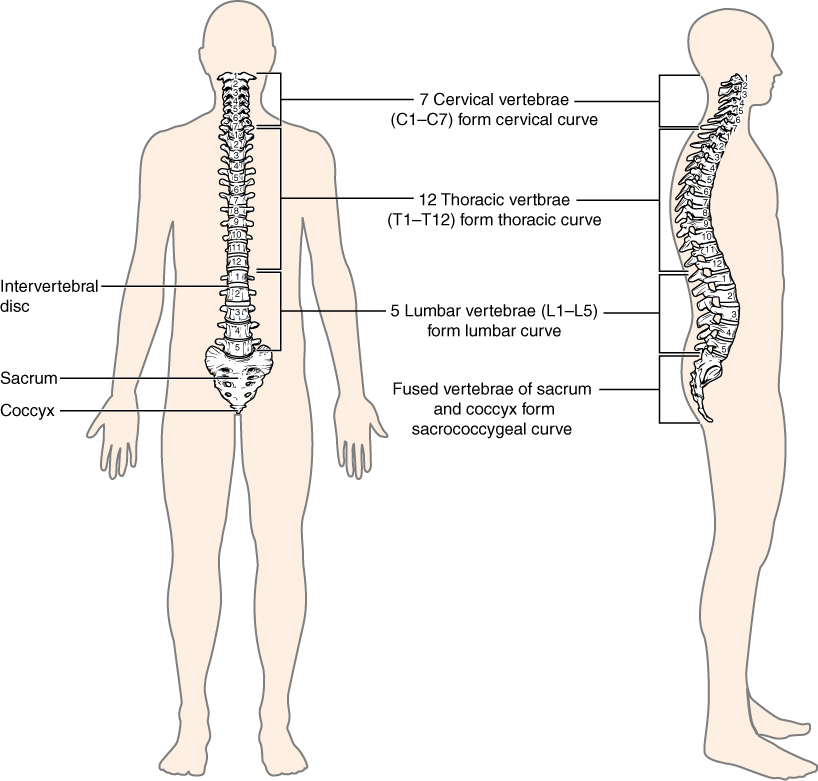

For violists, the rotated head, tilted neck and raised left shoulder translates to lateral deflection (in other words, horizontal tilting) of the lumbar and thoracic spine (Watson, 2009). This posture also leads to muscle fatigue, for example, the trapezius raising the left shoulder, and moreover if you have the tendency to rotate your left shoulder forward (Watson, 2009). Furthermore, rotating your left shoulder means your thoracic and lumbar spine curves towards the right as the cervical spine compensates the asymmetrical load by tilting left.

If we apply the rule of thumb (using larger muscles) to the list above, that would mean the actions of raising and rotating your left shoulder inward to support your instrument should be kept to a minimum, or if possible, to find a set-up that can help you reduce lifting your shoulder. However, you can also direct questions to yourself to address why you may be lifting the shoulder despite having ample elevation for your instrument; is it possibly a physical response to the fear of dropping your instrument? Or are your arms finding it awkward to adjust to a new technique?

Although an 8-week study found no differences between participants with basic body awareness therapy, those who practiced body awareness technique did perceive “positive changes in breathing, muscular tension, postural control and concentration during […] sessions” (Fjellman-Wiklunda et al., 2004, p. 10). Suggestions for further studies with a longer study period were discussed in addition to the responsibility that teachers bear of instructing students about good posture due to the difficulties of implementing new knowledge once a posture has been established. On the other hand, similar to any asymmetrical instruments (strings, guitar, brass and flute), the prolonged adoption of any position also significantly increases the risk to injury (Watson, 2009; Horvath, 2010, Ramella et al., 2014).

[infobox color=”purple” textcolor=”#ffffff”]

Keep in mind!

Do not fret if you are finding it difficult to avoid certain aspects that are detailed above; being aware of these adoptions of posture is already a significant step towards optimizing your playing. You can also help yourself by:

relaxing, taking a break whenever needed and practicing slowly in order to apply these new concepts with ease

[/infobox]

Suggested Principles:

Although we cannot significantly alter the way we play viola so that it is no longer asymmetrical, we can minimize the degree which we deviate from normal erect postures (Watson, 2009). Watson suggests the following:

-keeping your shoulders in line with your hips (avoid twisting the spine)

-minimal lifting of shoulders

-minimal forward rotation (or none if possible) of left shoulder

-keeping head facing forward (avoid twisting the neck)

-instrument at the side, keeping music directly right in front

These principles can also be minimized with the help of your instrumental set-up, which is discussed in this blog here: The Search for Ease: Violin Set-Up Guide.

Other factors that contribute to achieving your optimal posture: (Watson, 2009; Horvath, 2010)

-reduce tendencies of leaning forward (or even standing on your toes) for prolonged periods

-take frequent short breaks

-strengthen your erector spinae

-adjust music stand placement

be aware of these negative influences on posture:

-tension in back muscles, shoulders, neck, arms as a result of performance anxiety

-fear of mistakes

-concern of instrument slipping

-maintaining a conscious effort for tension awareness

Ultimately, the optimum posture on any instrument is being able to maintain a firm grip which is also flexible and allows your fingers to play relaxed.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Source Favourites“]

Here are some of my favourite sources which I encountered throughout my research for achieving an optimal posture. I highly recommend that you check them out! [/tab]

[tabs]

[tab title=”#1″]

The Watson textbook is an amazing guide that I was recently introduced to. It delves into the biological systems of our bodies while explaining the knowledge in a way that’s relevant for musicians, which I find really helpful.

[/tab]

[tabs]

[tab title=”#2”]

Janet Horvath’s “Playing (Less) Hurt” is a fantastic book which was written following her own experience of playing the cello with pain. Since its publication, she has brought a lot of attention towards eradicating the negative stigma of injured musicians. There are also sections of recommended stretches for practice breaks or during orchestra rehearsal which I personally enjoy.

[/tab]

[tabs]

[tab title=”#3″]

Informative video on muscles

What makes muscles grow? from TED-Ed by Jeffrey Siegel

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”References ” state=”closed”]

Fjellman-Wiklunda, A., Gripb, H., Anderssonb, H., Karlssonb, J. S., & Sundelina, G. (2004). EMG trapezius muscle activity pattern in string players: Part II –influence of basic body awareness therapy on the violin playing technique. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 33, 357–367.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2003.10.008

Guettler, K., Jahren, H., Hartviksen, K., Nesse T., & and Hansen, Ø. B. (1997). On the muscular activity of the performing violinist. Paper presented at

International Conference on Health and Musicians. York, England. Retrieved from http://knutsacoustics.com/files/yorkpaper-1997.pdf

Horvath, J. (2010). Playing (less) hurt: An injury prevention guide for musicians. New York: Hal Leonard Books.

Kumar, S. (2008). Biomechanics in ergonomics. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis.

Prosser, R., & Conolly, W. B. (2003). Rehabilitation of the hand and upper limb. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Ramella, M., Fronte, F., & Converti, R. M. (2014). Postural disorders in conservatory students: The diesis project. Medical Problems of Performing

Artists, 29 (1), 19–22.

Rothwell, J. (1994). Control of human voluntary movement (2nd ed.). London, UK: Chapman & Hall.

Turner-Stokes, L., & Reid, K. (1999). Three-dimensional motion analysis of upper limb movement in the bowing arm of string-playing musicians.

Clinical Biomechanics, 14, 426-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(98)00110-7

Watson, AHD. (2009). The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury. UK: Scarecrow Press.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Image References” state=”closed”]

1625 ter Brugghen Sänger mit Saiteninstrument anagoria, Hendrick ter Brugghen, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1625_ter_Brugghen_S%C3%A4nger_mit_Saiteninstrument_anagoria.JPG

Body Movements I, Tonye Ogele CNX, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Body_Movements_I.jpg

Trapezius back2, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trapezius_back2.png

Levator scapulae muscle back, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Levator_scapulae_muscle_back.png

Pectoralis minor muscle frontal, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pectoralis_minor_muscle_frontal.png

Serratus anterior muscle animation small.gif, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Serratus_anterior_muscle_animation_small.gif

Rhomboid major muscle back.png, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rhomboid_major_muscle_back.png

Latissimus dorsi muscle back.png, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Latissimus_dorsi_muscle_back.png

1119 Muscles that Move the Humerus.jpg, OpenStax, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1119_Muscles_that_Move_the_Humerus.jpg

Teres major muscle back.png, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Teres_major_muscle_back.png

Subscapularis muscle animation3.gif, Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Subscapularis_muscle_animation3.gif

1120 Muscles that Move the Forearm Humerus Flex Sin.png, CFCF, via Wikimedia Commons https://sco.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1120_Muscles_that_Move_the_Forearm_Humerus_Flex_Sin.png

1118 Muscles that Position the Pectoral Girdle, OpenStax, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1118_Muscles_that_Position_the_Pectoral_Girdle.jpg

1120 Muscles that Move the Forearm Antebrach. Sup. Flex. Sin.png, CFCF, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1120_Muscles_that_Move_the_Forearm_Antebrach._Sup._Flex._Sin.png

1120 Muscles that Move the Forearm Antebrach. Prof. Flex. Sin.png, CFCF, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1120_Muscles_that_Move_the_Forearm_Antebrach._Sup._Flex._Sin.png

Illustration of a cartoon cow, lemmling, via Free Stock Photos.Biz, http://www.freestockphotos.biz/stockphoto/10675

715 Vertebral Column, OpenStax College, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:715_Vertebral_Column.jpg

Musical Instruments Violin Music Cat Violinist, via Max Pixel, http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com/Musical-Instruments-Violin-Music-Cat-Violinist-1802021

[/toggle]

[/accordion]