Despite the many recent advancements in open music education through online platforms such as YouTube, toneBase, and MasterClass, high-quality advice on piano playing is for the most part still restricted to those lucky enough to study in a conservatory environment. Needless to say, when it comes to private teaching misinformation abounds, as there is no guarantee on the quality of information passed down to students. Anyway, regardless of the level of teaching, since piano teachers are not movement scientists, the physical aspect of piano playing is usually taught in general terms largely reliant on one’s personal bodily intuition, which can vary vastly from person to person.

In this blog post, my goal is to touch on what I feel are some important basic pillars of piano playing that may have been neglected in many students’ training, as was the case for myself until I entered music university at age 18.

Now, what sets this blog post apart from all the other well-intentioned misinformation floating around on the internet?

I’ll be using scientific sources to support my statements whenever possible, hopefully allowing piano students of all levels to make their own educated decisions to decrease wasted time, effort, and risk of injury in their piano playing journeys. References to Josef Lhevinne’s Basic Principles in Pianoforte Playing, a classic in piano pedagogy literature, when relevant will show that empirical and intuitive understandings of piano playing tend to support, rather than contradict each other!

If You Can Play it Slowly, You Can Play it Quickly

Motor Learning Strategies

If you’re a classical music student, you’ve probably seen this viral video:

All jokes aside, piano playing has been reported to be as fast as 30 notes per second! (Globerson & Nelken, 2013) It should be no surprise that at this speed, it is impossible to consciously plan out each finger movement. While it is true that slow practice is essential to initially learning the correct notes of a passage (Watson, 2009, p. 251), when it comes to eventually executing said fast passage at full speed, a pianist must rely on “automaticity”, where an entire sequence of fast actions is encoded in the brain as one single motor plan, as opposed to individual movements – this is often referred to colloquially (and incorrectly) as “muscle memory”. Of course, in a high-pressure performing situation, it is very easy to begin doubting in automatic ability, resulting in a performance mishap! To prevent such an occurrence, the performer should try to only focus consciously on larger scale tasks such as phrasing and structural levels, in order to avoid disrupting the automaticity of fast passages (Globerson & Nelken, 2013).

“Memorize phrase by phrase, not measure by measure… When you remember a poem, you do not remember the alphabetical symbols, but the poet’s beautiful vision, his thought pictures. So many students waste hours of time trying to remember black notes. Absurd! They mean nothing. Get the thought, the composer’s idea; that is the thing that sticks.” (Lhevinne, 1973, p. 43)

The Golden Tone Which Comes From the Heart

Tone production

Vladimir Horowitz was perhaps the greatest and most individual pianist of the 20th century, owing not only to his superhuman virtuosity, but his simply unmatched tonal palette as well. Roughly speaking, individuality in piano playing can be boiled down to one’s execution of rubato, voicing, and most elusively, tone colour. At the physical level, tone colour can be described as the unique keystroke (attack and release) dynamics of each pianist. Without knowing it, we pianists finely coordinate our wrist and elbow motion to tailor the acceleration and force given to the playing of each note, and it is this delicate control of dynamics which allows us to express the full range of emotions (Wang et al., 2023).

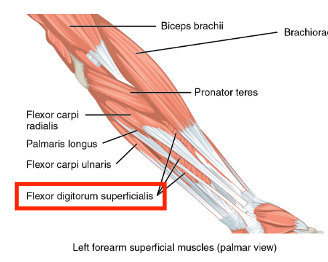

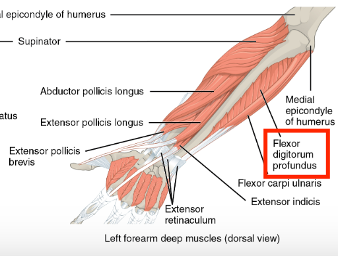

When it comes to controlling the above-mentioned keystroke dynamics, we rely not so much on muscles in the hand, but actually on muscles in the forearms whose primary function are to control finger movement (Minetti et al., 2007), pictured below:

(Openstax, 2016). CC BY 4.0

For more information, this excellent webpage (link) from the American Society for Surgery of the Hand gives concise and comprehensive explanations about the functions of the muscles in the shoulder, arm, and hand.

Why Does My Back Hurt???

Posture and Trunk Motion

(Piscano, S., 2017). CC BY 2.0

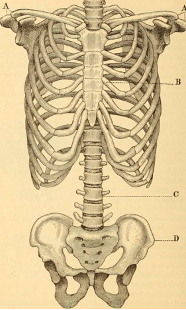

The use of posture and body movement are somewhat controversial in piano playing; although each person does need to find what works for themselves personally, here’s what can be said based on empirical findings. According to research by Verdugo and colleagues (2020), the “kinematic chain” of a pianist starts not just from the shoulder, but extends all the way from the trunk to the fingertips. That is to say that motion of the thorax and pelvis, pictured below, play an important role in sound production, even though these body parts are not directly connected to the keyboard.

(Hewes, H., 1900). CC0 1.0

Why? Contrary to what you might expect, it is not just the downward, but also the forward movement of our arms and fingers that go into each keystroke. Very conveniently, trunk motion can provide forward movement to all the upper limbs at once, and with relatively little effort, compared to using the arms or hands alone.

“Note that instead of sitting bolt upright, as the pictures in most instruction books would have the pupils do, he is inclined decidedly toward the keyboard. In all his forte passages he employed the weight of his body and shoulders. This was most noticeable; and the student should remember that when playing a concerto, [Anton] Rubinstein could be heard over the entire orchestra playing fortissimo. The piano seemed to peal out gloriously as the king of the entire orchestra; but there was never any suggestion of noise, no disagreeable pounding.” (Lhevinne, 1973, p. 31)

Trunk movement can also be a necessary strategy to compensate for natural differences in body proportions; for instance, a pianist with shorter arms will require more side-to-side trunk movement to reach extreme ends of the keyboard. It is worth noting that expert pianists tend to use more trunk motion than less experienced pianists (Turner et al., 2022).

The Elephant in the Room

Arm Weight and Finger Playing Technique

Among all of these important topics, playing technique still remains the hottest among piano students. You might have heard of different national “schools” of piano playing which each have their own technical and stylistic preferences; however, what all students should know regardless of pedagogical school or lineage, are the two main physiological mechanisms that are generally used in playing (Hmelnitsky & Nettheim, 1987), which we can call “weight” and “finger” playing.

In weight playing, the upper arm hangs freely, and the forearm is held in place by the downward force of gravity, opposed by the upward resistance of the keyboard. The weight of the arm is shared between the shoulder and the keyboard, and the only job of the muscles is to further stabilize this effect. In this way, the arm, wrist, and hand can be controlled bottom-up from the fingertip!

In finger playing, instead of using gravity against the resistance of the keyboard, the shoulder works alone to suspend the arm over the keyboard. The shoulder muscles contract to stabilize the upper arm, the upper arm muscles contract to stabilize the forearm, and finally the forearm muscles contract to stabilize the fingers. Finger playing technique was suitable for pianos in earlier eras which had lighter action (Horowitz, 1932), but is certainly no longer sufficient to accomplish the technical feats required to be performed on today’s concert grand piano. It is no wonder that this process causes more strain and a greater risk of injury!

“Perhaps the best general principle is the acquisition of the habit of playing with an extremely loose, floating hand. Rigidity of muscles and velocity never go together.” (Lhevinne, 1973, p. 46)

Don’t Be Like Bob

Injury Prevention

(Guo, C., 2024). CC0 1.0

PRMDs, or Playing-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders, are a risk for amateurs and professionals alike who practice for long periods each day. Particular behaviours that increase risk of PRMDs include the following:

- Elevated shoulders – indicates unnecessary tension in upper body, and that upper arms are not hanging freely.

- Trying to maintain a neutral straight wrist posture at all times – requires forearm muscles to be constantly working against eachother to maintain this position, which is neither comfortable nor helpful for playing.

- Jerky and linear movement patterns (e.g. only using horizontal motion to move from side to side of the keyboard)- requires activation of forearm muscles and tendons to acccelerate and decelerate; circular movement patterns allow more freedom of control.

- Octave playing – requires the simultaneous flexing and stretching of the joints, easily causing high amounts of tension in the hands and wrist.

(Allsop & Ackland, 2010)

In addition to risk factors specifically associated with piano playing, it is necessary to pay attention to how you carry out daily and work activities. Stressors from daily life or work such poor posture, repetitive movements, and lack of psychological or emotional safety, can all carry over into your piano practicing session, thus increasing risk of PRMDs.

Although we all know that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, injuries will inadvertently occur, and it is important to know how and where to seek help. Unfortunately, music educators are usually not required to be knowledgeable about PRMDs, and on the flip side medical practitioners may not be experienced in dealing with musician-specific issues. Luckily, the number of clinics and resources geared towards treating musicians have increased in recent years. For pianists, I highly recommend this blog post (link) from a previous student about a common PRMD called De Quervain’s syndrome, and which also provides an excellent overview of conservative treatments that could be effective for many PRMDs.

Thanks for reading!

Works Cited

Allsop, L., & Ackland, T. (2010). The prevalence of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in relation to piano players’ playing techniques and practising strategies. Music Performance Research, 3(1), 61–78. https://musicperformanceresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Allsop-Vol.-3.1-61-78.pdf

Globerson, E., & Nelken, I. (2013). The neuro-pianist. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2013.00035

Hmelnitsky, I., & Nettheim, N. (1987). Weight-bearing manipulation: A neglected area of medical science relevant to piano playing and overuse syndrome. Medical Hypotheses, 23(2), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9877(87)90156-3

Horowitz, V. (1932). Technic the Outgrowth of Musical Thought. Analytical Musicology & the Piano: Papers of Nigel Nettheim and Others. https://nettheim.com/horowitz/horowitz32.html

Minetti, A. E., Ardigò, L. P., & McKee, T. (2007). Keystroke dynamics and timing: Accuracy, precision and difference between hands in pianist’s performance. Journal of Biomechanics, 40(16), 3738–3743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.06.015

Lhévinne, J. (1973). Basic principles in pianoforte playing. Musical Scope.

Turner, C., Visentin, P., Oye, D., Rathwell, S., & Shan, G. (2022). An examination of trunk and right-hand coordination in piano performance: A case comparison of three pianists. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.838554

Verdugo, F., Pelletier, J., Michaud, B., Traube, C., & Begon, M. (2020). Effects of trunk motion, touch, and articulation on upper-limb velocities and on joint contribution to endpoint velocities during the production of loud piano tones. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01159

Wang, H., Nonaka, T., Abdulali, A., & Iida, F. (2023). Coordinating upper limbs for octave playing on the piano via neuro-musculoskeletal modeling. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 18(6). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/acfa51

Watson, A. (2009). How the Performance of Music Affects the Brain. In The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury (pp. 232-275). Scarecrow Press.

Images

Guo, C. (2024). Don’t be like Bob. Imgflip. CC0 1.0. https://imgflip.com/memegenerator/355975127/Be-Like-Bob

Hewes, H. (1900). Anatomy, physiology and hygiene for high schools. Picryl. CC0 1.0 https://picryl.com/media/anatomy-physiology-and-hygiene-for-high-schools-1900-14758414346-e7296d

Openstax. (2016). Muscles that Move the Forearm. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1120_Muscles_that_Move_the_Forearm.jpg.

Piscano, S. (2017). Daniil Trifonov at Carnegie Hall. Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Daniil_Trifonov_at_Carnegie_Hall_3.jpg.