Over the last forty years it has become widely known that instrumental musicians experience musculoskeletal pain or discomfort at a shockingly high rate (Middlestadt & Fishbein, 1989; Larsson et al.,1993; Steinmetz et al., 2015). Much of this musculoskeletal distress can be attributed to overuse or misuse. Overuse, according to Bird (2013), is in reference to the rigorous demands on musicians that mirror the type of repetitive stress experienced by athletes referred to as ‘overtraining syndrome.’ Another cause of these high reports of pain and injury, I posit, is caused by misuse, referring to inefficient or uninformed use of muscles causing strain and discomfort. The latter will be discussed in further detail later on.

While there is limited data available on the prevalence of pain in conductors, the data we do have indicates they, too, are at a high risk. A 2024 survey by Zão et al. measured the prevalence of pain in student and professional musicians. Among the participants were 14 conductors, representing 2.4% of all participants. Of the conductors surveyed, 10 of the 14 (71.4%) reported experiencing performance-related pain (Zão et al., 2024). In 2018, an informal poll of 700 wind conductors by Dr. Courtney Snyder, Associate Director of Bands at the University of Michigan, revealed that 65% of respondents reported they experience shoulder pain during or immediately after conducting (Snyder & Phillip, 2018). But what is causing such high reporting of pain in conductors? As with instrumental musicians, it is likely that rigor and time spent performing is a contributing factor, but I believe there are certain risk factors putting select subgroups of conductors at increased risk. For example, time spent on the podium surely has an impact on overuse for professional conductors who may have extended rehearsal hours over a short span of time leading up to a concert performance. On the other hand, conductors of larger ensembles like a campus group, community band, or large high school program, for example, may experience added muscle stress from feeling they need to conduct bigger to be seen. Similarly, conductors of less experienced musicians may over-conduct because they observe or suspect the musicians are looking down at their music more and up at the conductor less. In beginning to address this issue of the high prevalence of pain in conductors, let us go back to Conducting 101 to review what ‘proper’ or ‘ideal’ use looks like.

The Conductor’s ‘Stance’

If you were to open any textbook on conducting, the first unit or chapter is almost certainly about the conductor’s “stance” or “posture.” Most conducting texts agree that a grounded but available foundation is imperative to expressive conducting (Haithcock et al., 2020; Bailey & Payne, 2014; Wittry, 2014; Jordan, 2009; Hunsberger & Ernst, 1992; Green, 1981). But what does it mean to be ‘grounded’ and ‘available’?

Haithcock et al. (2020) simply refers to availability as the “body’s ability to move naturally without tension” (p.19). In addition to limiting the conductor’s artistic expression, tension puts them at risk of developing back, shoulder, or other musculoskeletal problems that threaten the longevity of a conducting career (Wittry, 2014). According to the movement studies of Laban and Bartenieff, availability is just one element of a balancing body; the four characteristics being: purposeful initiation of movement, mindful connection of body parts to one another, sequencing of movement through an efficient delivery system, and, lastly, availability made possible through fluid body connectivity that is uninhibited by tension (Wahl, 2019). As explained further by Haithcock, when we allow our bodies to be available, that is, not locked or restricted by tension, the natural connections from our fingertips to our shoulder to our neck and back are able to work together to allow for expansive and fluid movement.

So where are conductors going wrong? Perhaps we just need some additional tools and practices to help in the development of mental and physical awareness of musculoskeletal connections. This is a fundamental concept of two helpful techniques: Body Mapping and Alexander Technique. Let’s explore them further.

Tools of the Trade: Body Mapping and the Alexander Technique

At the center of both of these techniques is the idea that, by creating mind-body awareness, one can make decisions to move more efficiently and fluidly, thus reducing tension and preventing pain, discomfort, or injury. In other words, by having a clear mental map of how our muscles work together to achieve an action, we can more easily ground ourselves in our movement through connection with our core. When we use a larger system of muscles we distribute the effort over a larger area, which engages the core. Doing so also prevents putting unnecessary strain on smaller muscles or muscle groups. The classic example of this use of gross motor skills, as opposed to just fine motor, is “lifting with your legs, not your back,” which we do because our legs can bear heavier loads (Cleveland Clinic, 2023). According to Buchanan et al. (2014), this concept of creating a mind-body awareness is the underlying premise of Body Mapping (BMG) and is the key to freedom of movement. In their study on the impact of BMG on university music students’ perception of their performance, they found that students who reported they were ‘very comfortable’ regarding their confidence and understanding in Body Mapping concepts also reported that BMG changed their approach to performance. These participants noted BMG concepts gave them greater confidence in performance and helped them feel more physically grounded, leading to more artistic freedom (Buchanan et al., 2014).

Body Mapping is the practical application of the concepts and theories of the Alexander Technique. Informed by his years as an Alexander Technique teacher, Bill Conable, professor emeritus of cello at Ohio State University, developed the concept of the Body Map when he realized his students were moving according to how they thought their musculoskeletal system was structured rather than how it was actually structured. This ‘misuse,’ as I referred to it earlier, was inhibiting this student’s full artistic potential. When the student’s movement was informed by an understanding of their physiology, their movements became more efficient and expressive (Conable, 2000). While BMG focuses primarily on one’s mind-body awareness and how it relates to specific movements, the Alexander Technique (AT) is a practical method of “kinesthetic re-education” to replace unfavorable postural habits with favorable, more efficient ones. In AT, according to Fitzgerald, et al. (1995), “movements in accordance with the technique are characterized by economy of effort and a balanced and appropriate distribution of tension (not an absence of tension but no more than is necessary). Such optimal functioning constitutes ‘good use’ and deviation from it is termed ‘misuse.’” (p.129)

The Alexander Technique was conceived by actor F.M. Alexander (1869-1955). He was suffering from vocal problems and, rather than undergo an unreliable and possibly dangerous surgery, he decided to observe himself in a mirror every day to determine what might be causing his issues. This self-exploration practice led to discoveries that developed into the teaching technique that we know today (TEDx Talks, 2018). Here is more on the origin of the Alexander Technique and its basic concept:

August Berger (2018), Change your life with Alexander Technique, TEDxYouth@NBPS., CC BY–NC–ND 4.0 International

Summary of the Fundamental Principles of AT

The Use of Self: Recognizing that the entire body is always “in use,” even those that are unmoving.

The Primary Control: Every localized action (activity of the limbs, hands, and fingers or lips, tongue, and jaw, for example) must be in harmony with and originate from coordination with the head, neck, and spine.

Sensory Awareness and Conception: The concept of proprioception – our kinesthetic awareness of all muscular activity; being aware of the orientation of our body in space, movement of our body and limbs, the effort or tension required to complete an action, perception of fatigue, balance, etc.

Inhibition: Recognizing misuse that results from a habitual response to a specific stimulus and inhibiting/not consenting to this habitual reaction that causes misuse in the self; e.g. recognizing when one rushes the fingers through a technical passage or tensing the shoulders when one is performing a solo piece on stage.

Direction: Self-directed (or teacher-directed) reminder to stop doing the ‘misuse,’ for example a reminder to “think up” or “let the neck be free”; functions to link a mental command with a tangible physical reality and sensorial feedback.

Action: Choosing to do an action that typically results in misuse differently and in a way that includes self-awareness, inhibition, and direction.

(Alcantara, 1997)

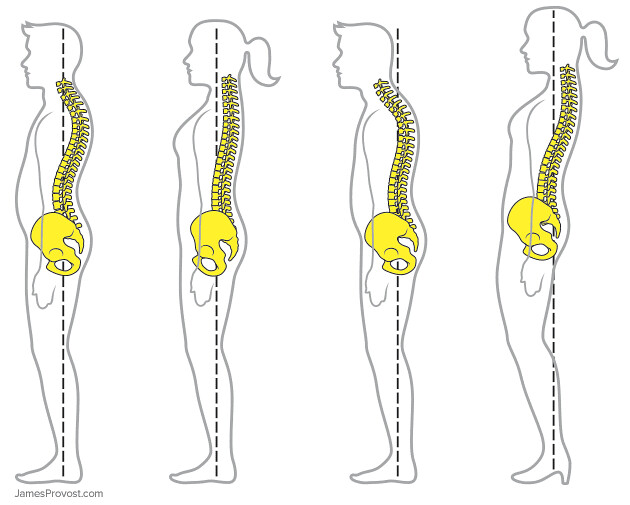

James Provost, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Alexander Technique on the Podium:

So how can we apply these principles to the conductor? In returning to fundamentals of conducting and the conductor ‘stance,’ we see a great deal of overlap with the fundamentals of the ‘balancing body’ mentioned earlier:

‘Purposeful initiation of movement’:

- Primary Control

When we coordinate our movements from a place of center, we can feel more grounded in our conducting.

‘Mindful connection of body parts to one another’:

- Sensory Awareness and Conception

By creating a mental map of our body’s musculoskeletal system works together we can move more fluidly through space.

‘Sequencing of movement through an efficient delivery system’:

- Primary Control

- Direction

Through directives and reminders such as ‘remember to feel grounded through the feet’ or to initiate movement from our center, we reinforce favorable habits that provide us more freedom and stability to be expressive.

‘Availability uninhibited by tension’:

- Use of Self

- Action

- Inhibition

When we think of our conducting body as ‘in use’ even in stasis it helps us find our mental quiet and center before we put the hands up to begin. Through action and inhibition we can choose to build and reinforce positive habits that prevent tension from creeping into our gestures and movements.

Conducting Anatomy 101: Body Mapping for the Conductor

The Conductor’s Stance: Revisited

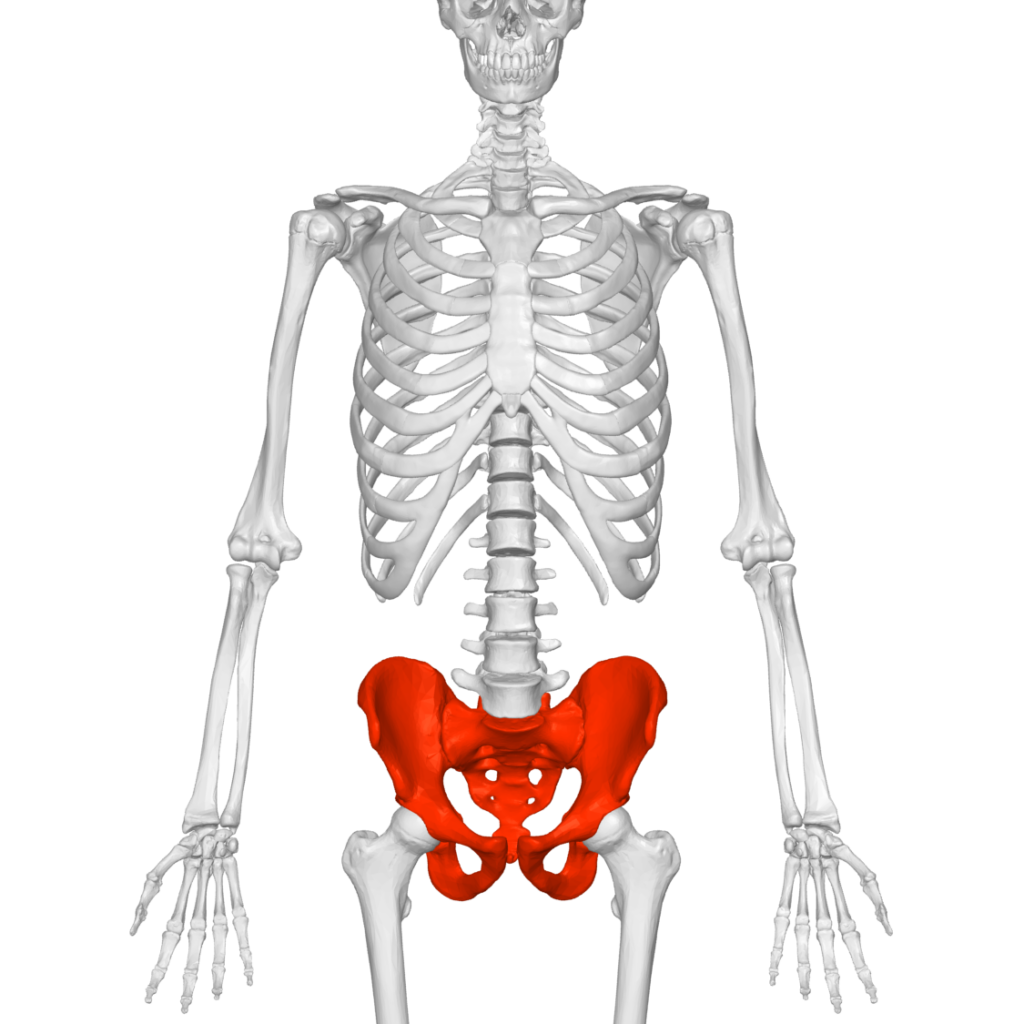

Let us begin with building a balanced conductor stance. Haithcock et al. (2020) uses the term “balancing body” to imply an active process of adjusting weight in a fluidly moving body, as opposed to “posture,” which implies a fixed, inactive position (p.25). If we begin with the “primary control” concept proposed by the Alexander Technique, we start with ensuring our skull is balanced on the top of our spine, connected by the atlanto-occipital joint (or AO joint) (Brewster, 2019). The weight of our skull is aligned over our center of gravity located in the pelvis, or ‘pelvic bowl,’ which holds the abdominal muscles and organs (Haithcock et al., 21-22). In a balanced stance, our center of gravity is then evenly distributed between our two feet, which act as tripods. The three balance points in the foot are 1) the ball joint of the big toe, 2) the ball joint of the little toe, (these are called metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints), and 3) the heel, specifically the talus bone, which transmits weight from the body to the foot (MacGregor & Byerly, 2023). When we align the skull over the pelvic bowl and distribute our weight evenly over our two tripods, we create a balanced stance free of tension caused by counterbalancing that permits us to use the rest of our conducting mechanism freely and fluidly.

The Conducting Mechanism

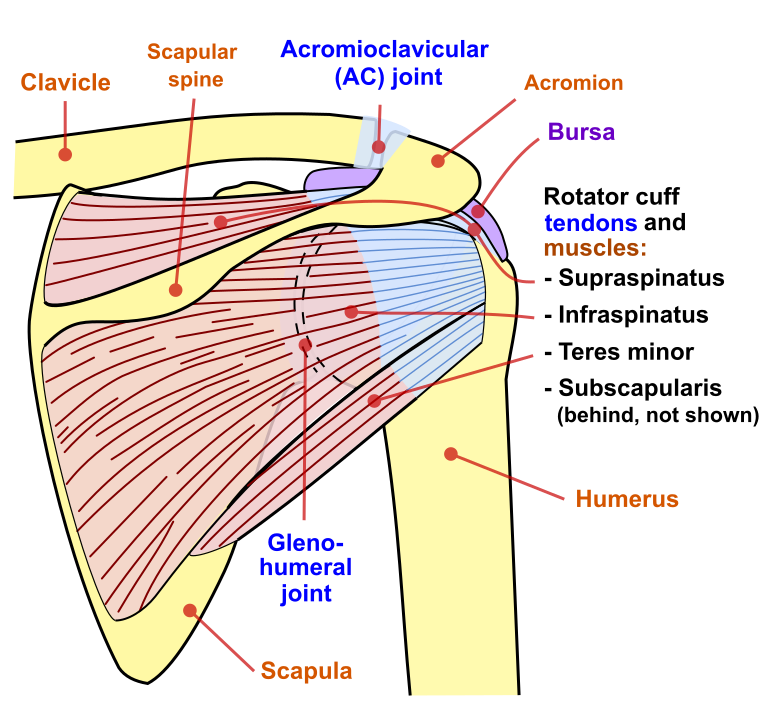

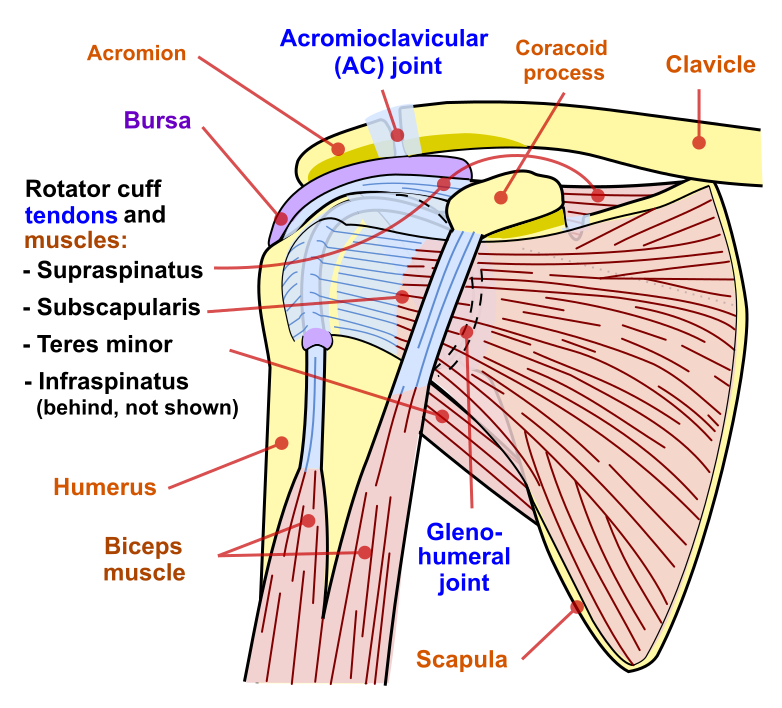

It is a misconception that the joint where the arm bones connect directly to the trunk is the shoulder. In actuality, the scapula (or “shoulder blade”) is a floating bone secured to the rib cage by muscle. The scapula is tethered to the torso by the clavicle (or “collar bone”) at the acromioclavicular joint, which in turn connects to, or “articulates” with, the sternum (or “breastbone”) at the sternoclavicular joint (Watson, 2009, 44-45). Now knowing that the shoulder blade is free to rotate around the rib cage and the ability of the collar bone to act as a lever rather than fixed in position, consider the availability and freedom of the arm and the range of motion this creates.

The top of the humerus (upper arm bone) is held in the socket joint by four muscles: the supraspinatus (responsible for abduction), the infraspinatus (rotates the arm outward along its vertical axis), the teres minor, and the subscapularis, which rotates the arm inward. The three large muscles responsible for arm movement are the trapezius, which attaches to the vertebral column and back of the skull, the deltoid, which aids the supraspinatus in abduction, and the latissimus dorsi, which pulls the raised arm down (adduction). In the front of the shoulder, the shoulder blade is attached to the ribcage by the serratus anterior and the pectoralis minor (Watson, pp.42-46). All to say, when we use our conducting mechanism, there are many muscles assisting us. Rather than simply visualizing movement initiating from the shoulder, try visualizing the large muscles of the chest and back that make the movement possible and aid in the heavy lifting. When we realize how many muscles are in action, we can avoid placing unnecessary strain on only a select few. But can this additional mindfulness really have that great an impact on our performance? Let’s explore our newfound availability

Trusting the Delivery System

Leading with the fingertips, reach out as if to give a handshake. Notice how the rest of the arm follows: fingertips to wrist, wrist to elbow, elbow to shoulder, shoulder to torso. When the hand leads, the rest of the arm naturally follows with ease. When we maintain a desirable delivery system and lead from the hand it not only provides more fluidity to our gesture, but also allows the ensemble to focus on the action point (at the hand or tip of the baton) and more easily track and predict its movements.

Avoiding occupational hazard: Artful Conducting Without the Risk of Injury

Numerous studies have demonstrated that regular practice of mindfulness techniques like Body Mapping and Alexander Technique has a variety of positive impacts on pain reduction, performance, and everyday life. Music students enrolled in a fifteen-week university course on Body Mapping reported a “greater confidence” in their music performances as well as indicated feeling more grounded, which resulted in feelings of more artistic freedom (Buchanan et al., 2014). Several studies have been conducted using university music students enrolled in Alexander Technique courses as well. The data collected in these studies revealed several physical impacts of AT on performers’ experiences including reduced heartrate variance during performance indicating a reduction in physiological responses to performance anxiety, reduction in muscle tension while performing, and improved instrumental technique during performance (Fitzgerald et al., 1995; Davies et al., 2020). The benefits of BMG and AT go beyond music performance, however. Alexander Technique principles have been shown to have benefits in our regular day to day such as improved mindfulness and concentration (Kim et al., 2014). More significantly, in a substantial study by Little et al. (2008) it was found that regular practice and application of Alexander Technique led to a reduction in pain and disability in patients with chronic back pain. It is impossible to refute the plethora of benefits these techniques can have for both musical and non-musical activities, so how can conductors use these practices to best reap these benefits?

While many conducting texts tell us we need to stand up straight with our feet shoulder width apart and our arms extended in front of us in a position that welcomes sound, few provide the mindfulness tools to turn this very static position into one that is free. By practicing more mindfulness and mind-body awareness, not only can we move with more freedom and availability, but we can be better equipped to recognize strain, misuse, and fatigue so that we may make adjustments to our habits, thus increasing our endurance and capacity for music making and prolonging our conducting career.

But every conducting career is different! These adjustments may come in the form of refining our conducting technique and use of the conducting mechanism, but it could also mean adjusting the way we run rehearsals or rehabilitate off the podium. For example, in educational settings this could mean taking breaks from conducting during rehearsals to allow the ensemble to instead rely on their ears, which can also be a great opportunity for teaching individual musicianship to your ensemble; by not relying on the conductor, musicians are forced to listen more and take ownership and responsibility for their musical contribution to the ensemble. For the professional conductor, it is important to take the time to rest and recover between performances, perhaps using ice, heat, or stretching to rehabilitate muscles. In any case, having a greater mind-body awareness gives us the power to make decisions to remedy any problems that may arise and address them before they become a chronic issue. At the end of the day, being mindful and listening to the body is the best way to learn from our habits and form new ones to ensure a long and healthy artistic career.

Other Recommended Reading for Pain and Injury Prevention:

Horvath, J. (2009). Playing (less) hurt: An injury prevention guide for musicians.

Horvath’s book is divided into four sections. The first, Overview of How Injuries Can Arise, discusses the prevalence of injury among instrumental musicians and defines overuse. Additionally, she lists some of the causes of overuse and provides some of the warning signs of when a musician might be heading the direction of developing a serious injury. Part 2, Explanation of Various Injuries, details some of the most prevalent injuries among musicians while providing some tips and tricks for avoiding these types of injuries. Part 3, Preventative and Restorative Approaches, contains a great deal of information including guidelines for teachers to promote healthy habits in their students, recommended stretches, suggestions for chair-related low back pain, hearing health, rehabilitation, suggestions for a healthy practice routine, etc. The final section, Further Help is Available, is long list of additional print and digital resources, clinics, etc. It also includes a section on training for classroom teachers.

McAllister, L. S. (2020). Yoga in the music studio. Oxford University Press.

McAllister suggests yoga should be a regular part of every musician’s life as a way of developing awareness of breath, body, and movement. Chapter 1 is a background on the practice of yoga, a description of the types of poses and their benefits, and an outline of the principles of the practice for teachers to use. Chapter 2 contains specific practices, Chapter 3 is research-oriented and explains how yoga has proven beneficial. Chapters 4-7 offer practical strategies for music teachers to use at different stages of their students’ development.

Olson, M. (2009). Musician’s yoga: A guide to practice, performance, and inspiration (J. Feist, Ed.). Berklee Press.

Musician’s Yoga contains ten chapters that can be divided into three topics. The first deals with how to use visualization, breath, and meditation for music making. The second “section” focuses on the physical body and movement and contains a plethora of techniques for body alignment, including yoga poses and stretches targeting upper body, lower body, spine, and balance. The third topic, more holistic in nature, explores self-care exercises for relaxation, sleep, waking up, and a guide on how to develop your own daily practice routine.

Paull, B. & Harrison, C. (1997). The athletic musician: A guide to playing without pain. Scarecrow Press.

While not specifically addressing conducting, this book discusses in detail the areas of the body where conductors are also likely to experience pain and tension. The book provides tools and tips for the professional musician, such as suggested ergonomics, exercise protocols, suggestions for practicing, suggestions for work, and what to do should injury occur.

Taylor, N. (2016). Teaching healthy musicianship: the music educator’s guide to injury prevention and wellness. Oxford University Press.

While the text does not directly address the conductor, it does offer general guidelines for alignment and stretches that can be done on the podium and when standing for long periods of time in addition to advice on bringing more awareness to how we perform daily tasks. There are also chapters entitled “When It Hurts,” offering tools for addressing strain or discomfort.

Bibliography

Alcantara, P. (1997). Indirect proceduares: A musician’s guide to Alexander technique. Oxford University Press.

Bailey, W. & Payne, B. (2014). Conducting: The art of communication (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Bird, H. A. (2013). Overuse syndrome in musicians. Clinical Rheumatology, 32(4): 475–79.

Brewster, M. (2019, June 3). Alexander technique anatomy: 101. Alexander Technique with Mariel Brewster. https://www.alexandertechniqueamelia.com/post/alexander-technique-anatomy-101

Buchanan, H. J., & Hays, T. (2014). The influence of body mapping on student musicians’ performance experiences. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 15(7).

Cleveland Clinic. (2023, October 18). Gross motor skills. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/gross-motor-skills

Davies, J. (2020). Alexander Technique classes improve pain and performance factors in tertiary music students. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 24(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.04.006

Engel, F. (2025). The Alexander technique — what is it?. The Complete Guide to Alexander Technique. https://www.alexandertechnique.com/articles/engel/

Farrell, A. (2015). Stand on your bottom, what?! The truth about sitting. Alexander Technique London & Online: Improving Your Posture, Health and Performance. https://www.alexander-technique.london/2015/01/08/stand-on-your-bottom-what-the-truth-about-sitting/

Fitzgerald, D. F. P., Gorton, T. L., Valentine, E. R., Hudson, J. A., & Symonds, E. R. C. (1995). The effect of lessons in the Alexander Technique on music performance in high and low stress situations. Psychology of Music, 23(2), 129–141.

Green, E. A. H., Gibson, M., & Malko, N. (2004). The modern conductor : A college text on conducting based on the technical principles of Nicolai Malko as set forth in his The conductor and his baton (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Haithcock, M., Doyle, B.K., Geraldi, K.M., & Schweibert, J. (2020) The elements of expressive conducting. Conway Publications.

Hunsberger, D. & Ernst, R. (1992). The art of conducting (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Jordan, J. (2013). Conducting technique etudes: Laban-based etudes for class or individual practice. GIA Publications, Inc.

Jordan, J. (2011). The conductor’s gesture: A practical application of Rudolf von Laban’s movement language. GIA Publications, Inc.

Kim, S. Y., & Baek, S. G. (2014). The effect of Alexander technique training program: A qualitative study of ordinary behavior application. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 10(6), 357.

Knierim, J. (2020, October 20). Overview: Functions of the cerebellum. Neuroscience Outline: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences. https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s3/chapter05.html

Larsson, Lars-Göran, John Baum, Govind S. Mudholkar, & Georgia D. Kollia (1993). Nature and impact of musculoskeletal problems in a population of musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 8(3): 73–76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45440722.

Little, P., Lewith, G., Webley, F., Evans, M., Beattie, A., Middleton, K., Barnett, J., Ballard, K., Oxford, F., Smith, P., Yardley, L., Hollinghurst, S., & Sharp, D. (2008). Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 337, a884. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a884

MacGregor, R.& Byerly, D.W. (2023, May 23). Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb: Foot Bones.National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557447/

Middlestadt, Susan E., and Martin Fishbein (1989). The prevalence of severe musculoskeletal problems among male and female symphony orchestra string players.” Medical Problems of Performing Artists 4(1): 41–48.

Steinmetz, A., I. Scheffer, E. Esmer, et al. “Frequency, severity and predictors of playing-related musculoskeletal pain in professional orchestral musicians in Germany.” Clin Rheumatol 34, (January 2014): 965–973.

TEDx Talks. (2018, December 21). Change your life with the Alexander technique | August Berger | TEDxYouth@NBPS [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZQFdh41wXU

Wahl, C. (2019). Laban/Bartenieff movement studies: Contemporary applications. Human Kinetics.

Watson, A.H.D. (2009). The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury. Scarecrow Press, Incorporated. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=467511

Wittry, D. (2014). Baton basics: Communicating music through gestures. Oxford University Press.

Wolf, R. C., Thurmer, H. P., Berg, W. P., Cook IV, H. E., & Smart Jr., L. J. (2017). Effect of the Alexander Technique on muscle activation, movement kinematics, and performance quality in collegiate violinists and violists: A pilot feasibility study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 32(2), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2017.2014

Zão, Ana, Eckart Altenmüller, & Luís Azevedo (2024). Performance-related pain and disability among music students versus professional musicians: A multicenter study using a validated tool.” Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.) 25(9): 568–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnae032.

Zaza, Christine, Cathy Charles, and Alicja Muszynski (1998). The meaning of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders to classical musicians. Social Science & Medicine 47(12): 2013–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00307-4

Graphics

Anatomography, C2 from top animation, CC Attribution-Share Alike 2.1 Japan. https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/C2_from_top_animation.gif&tbnid=6IMjUpzVn6jJrM&vet=1&imgrefurl=https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:C2_from_top_animation.gif&docid=A_0cWtksuHZ__M&w=640&h=640&source=sh/x/im/m1/1&kgs=880332810a020b40

Arunakul, M., Amendola, A., Gao, Y., Goetz, J. E., Femino, J. E., & Phisitkul, P. (2013). Tripod Index: Diagnostic Accuracy in Symptomatic Flatfoot and Cavovarus Foot: Part 2. The Iowa Orthopaedic Journal, 33, 47–53. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256502098_Tripod_Index_Diagnostic_Accuracy_in_Symptomatic_Flatfoot_and_Cavovarus_Foot_Part_2

BodyParts3D, Pelvis, The Database Center for Life Science licensed, CC-BY-SA-2.1-JP. https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f6/Pelvis_%2528male%2529_01_-_anterior_view.png&tbnid=8yt8EFsGBcTQ-M&vet=1&imgrefurl=https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pelvis_(male)_01_-_anterior_view.png&docid=KHqLdxY1ENak7M&w=1125&h=1125&source=sh/x/im/m1/1&kgs=0d66fb2923f4aad2

James Provost, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https://live.staticflickr.com/3938/15533270900_118c00729b_z.jpg&tbnid=BVrWx75ZhufqIM&vet=1&imgrefurl=https://www.flickr.com/photos/jprovost/15533270900&docid=0cqDIEM9l56HSM&w=630&h=505&source=sh/x/im/m1/1&kgs=a37c1952b2935841

Jmarchn, Shoulder joint back-en, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://openverse.org/image/0eed8ab1-2b6c-4d32-ad0a-0b2a78fea516?q=shoulder+anatomy&p=6

Jmarchn, Shoulder joint front-en, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shoulder_joint-ca.svg

U.S. Air Force. (2018). U.S. Air Force 1st. Lt Christina Muncey, conductor [Photograph]. NARA & DVIDS Public Domain Archive. HYPERLINK “https://can01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnara.getarchive.net%2Fmedia%2Fus-air-force-1st-lt-christina-muncey-conductor-b74739&data=05%7C02%7Cisabelle.cossette1%40mcgill.ca%7C1104e131a0144915a8a408dd786c39a9%7Ccd31967152e74a68afa9fcf8f89f09ea%7C0%7C0%7C638799128421164809%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJFbXB0eU1hcGkiOnRydWUsIlYiOiIwLjAuMDAwMCIsIlAiOiJXaW4zMiIsIkFOIjoiTWFpbCIsIldUIjoyfQ%3D%3D%7C0%7C%7C%7C&sdata=BD3LQV2q3ZfMgQEJ3xMZF%2B7Qb6t4pdJPkqVnEFaRJLs%3D&reserved=0″https://nara.getarchive.net/media/us-air-force-1st-lt-christina-muncey-conductor-b74739.