Theo Lysyk

Rates of injury

In the musical profession, it seems that everybody has had or knows somebody who has experienced some kind of injury. Tendinitis and carpal tunnel syndrome in the wrist, tennis and golfers elbow, lower-back pain, and shoulder problems seem inescapable, as all of these syndromes and conditions rise again and again, shortening careers and losing valuable time and money that should be used on better things. It is well documented that musicians experience high levels of playing related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMD) and this rings true for percussionist populations, who have reported rates as high as 77% in a 2009 study (Sandell et al., 2009). Of these percussionists, 74% of drumset and timpani players, 79% of auxiliary players, and 89% of keyboard players report having experienced PRMDs. Injury is flat out detrimental for the growth of percussion in Canada.

According to Nadia Azar, “Musculoskeletal injuries occur when the demands placed on a tissue exceed its capacity to meet them. The greater the demands, and the lower the capacity, the greater the risk that an injury will occur” (2022). By understanding the physical demands and risk factors of the percussionist profession, increasing tissue capacity through training music-specific skills, improving posture, kinesthetic awareness and lifestyle, and implementing effective recovery methods, it is possible that we can prepare percussionists’ bodies to mitigate injury risk and perform at the highest level.

Azar also writes that “Embedding health promotion/injury prevention within post-secondary instrumental music programs can positively influence music students’ knowledge and attitudes toward health and engagement in healthy behaviors” (2022), meaning preventative education and injury prevention strategies should be taught to younger players from their teachers to reduce chances of injury.

This begs the question, what possible preventative measures can be taken by percussionists to reduce the likelihood of chronic injury?

In this post, I’ll be giving strategies to identify the risk factors and demands of the percussionist profession and mitigate them through practical guidelines to reduce their likelihood of injury. This will not guarantee that you won’t become injured, and it will not address injury assessment or therapy, but I will share some of the ideas in current literature in the musicological, performance science, and sports science domains about injury prevention and apply them to the profession of percussion.

What increases likelihood of injury?

Injuries exist in acute or chronic forms, with the former being attributed to a singular event that exceeds tissue capacity, and the latter being defined as “repeated submaximal loading that reduces the capacity to handle loading is reduced to the point where a load that was once acceptable is no longer tolerated and an injury occurs” (Azar, 2022).

In simpler terms, injuries appear in two ways: acutely and chronically. Acute injuries occur because of a catastrophic event that expose somebody to a great deal of force that exceeds their tissue capacity in one single moment. Slipping on the ice and spraining your ankle, falling and spraining your wrist, or whiplash from a fender-bender are all examples of this. These are difficult to predict, seem to come from chance, and are usually attributed to some combination of bad luck and/or decision-making. While acute injuries are obviously tragic and to be avoided, there is an element of luck and unpredictability that make acute injury prevention difficult to describe beyond “being careful”. However a musician should be careful, as acute injuries (at their worst) can end a musicians career or create a scenario that leads to long-term management of injured tissue or other chronic issues.

Chronic injuries develop slowly over time and are characterized by the slow degradation of a tissue’s capacity to perform a certain activity or movement. A small pinch in your finger that began at the end of a long practice session may spread to your wrist, and the little pain that used to be a mild annoyance slowly intensifies over days and weeks and turns into a deep burning sensation that interferes with your speed, clarity, and technique until you’re unable to play at all. To oversimply the phenomenon, what has happened is that your tissues have been exposed to 80-90% of their maximum capacity day-after-day, gradually wearing down and slowly reducing the capacity of the tissues until they cannot support practice like they used to.

In a study from Sandell et al., (2009) it is noted that most of the chronic PRMDs experienced by percussionists are in the hand and the lower back. Common chronic upper extremity injuries related to playing percussion include repetitive strain injuries (RSI) such as overuse syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and tendinitis. It may be helpful for percussionists to familiarize themselves with common injuries, so I’ve organized them in a table (Table 1) with the name of the syndrome, a description of the injury, potential symptoms, and possible ways to prevent them as described by Paola Savvidou in her 2021 book Teaching the Whole Musician: A Guide to Wellness in the Applied Studio and Alan Watson in his 2009 book The Biology of Musical Performance and Performance-Related Injury.

This is extremely brief summary, as the topic is far beyond the scope of this blog post. This should be seen simply as an introduction to common types of injuries percussionists face.

| Name | Description | Symptoms | Preventative Methods for Musicians |

| Generalized Pain/Overuse Syndrome/Repetitive Strain Injury | “…a condition arising as consequence of exceeding the biological or physical limits of the tissue” (Watson, 2009) | – General pain with repetitive motions – Pain may move around the body, such as from the hand to the shoulder – Pain may affect the musician when they perform daily activities | – Improving physical fitness – Adjusting/Improving posture -Adjusting/Improving technique – Improving instrument ergonomics – Reducing stress or other lifestyle stressors |

| Muscle strain (muscle pathology) | Pain in muscles due to the acute or chronic breakdown of muscle fibers. | – Pain – Stiffness – Weakness – Swelling – Cramps or spasms – Loss of range of motion | – Reduce tightness in the muscles – Improve poor technique – Improve recovery time – Avoid practice without warming up |

| Myofascial Pain (muscle pathology) | Chronic and persistent pain in muscle and the tissue that surrounds the muscle. (known as fascia) | – Pain in specific or localized muscle – Trigger points of tight or sensitive muscle and fascia (also known as knots) that cause focal pain when aggravated | – Maintaining proper posture – Engaging in regular stretching and strengthening exercises – Avoiding repetitive strain or muscle overuse – Ergonomic modifications – Stress management techniques -Treatments include physical therapy, pain relief cream, myofascial release |

| Tendinosis (tendon pathology) | Tiny fractures in tendons without inflammation | – Pain – Loss of range of motion – Stiffness – Weakness | – Avoid chronic overuse – Treatments include physical therapy, exercises, steroid injection, surgery. May take a long time to heal, as long as 9 months. |

| Tendinitis (tendon pathology) | Inflammation and irritation of a tendon. The elbow, wrist, and thumbs are common areas of tendinitis for musicians. Irritation of the tendon at the elbow is called medial or lateral epicondylitis (also known as golfer’s elbow or tennis elbow) (Savvidou, 2021). | – Pain – Sensitivity to touch – Loss of range of motion – Stiffness – Discomfort – Inflammation | – Avoid chronic overuse – Treatments include physical therapy, exercises. |

| Tenosynovitis (tendon pathology) | Inflammation of the tendon sheath. Caused by overuse. An example is DeQuervain’s tenosynovitis which affects the tendons on the thumb side of the wrist. | – Pain – Swelling – Loss of range of motion | – Muscle stretching – Muscle strengthening – Treatments include ice and rest are immediate pain relief methods |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome (nerve pathology) | The compression of the medial nerve due to swelling within the ‘carpal tunnel’ located in the wrist. | – Numbness – Tingling – Pain – ‘Burning’ within the thumb, index, middle, and/or ring finger | – Proper warm up – Improving flexibility – – Improving body positioning – Improving ergonomics |

| Cubital tunnel syndrome (nerve pathology) | The compression of the ulnar nerve due to swelling within the ‘cubital tunnel’ located in the elbow. | – Numbness in arm or hand, particularly in the ring or pinky finger – Pain in the hand/finger – Pain in the inside of the elbow. | – Proper warm up – Improving flexibility – – Improving body positioning – Improving instrument ergonomics |

This table is only for disseminating information, not for diagnosis.

If you have chronic pain or suspect that you may be experiencing any of these injuries, it is recommended to see a medical professional. Pain is often the first warning sign. Some other warning signs that tell you when to see a doctor include shaking after playing, needing to stretch directly after playing, sudden or unusual tightness, physical and emotional fatigue, or discomfort (Savvidou, 2021).

Percussionist risk factors.

Mariam Webster defines risk factor as “something that increases risk or susceptibility”. In our case, we are discussing the different attributes of playing percussion that increases risk of injury. Unfortunately, exposure to these risk factors is a necessary part of playing percussion. However, we can employ strategies that increase our tissue capacity or lower tissue demand to decrease the severity of these risk factors when practicing and performing. In this section, I’m presenting and discussing some risk factors associated with percussion and offer some preventative measures to reduce risk of injury. These risk factors are repetitive instrument-specific movements, posture and ergonomics, and life habits and physical conditioning.

Risk factor: Repetitive instrument-specific movements.

Repetitive movements are necessary for practice and performance, and in order to improve, a percussionist must engage in the same techniques day after day. This constant engagement with specific movements and techniques is very demanding, and many biomechanical features of playing percussion become risk factors. Some of these risk factors identified by Azar for drumset players include flexion and extension of the wrist when playing with drumsticks, excessive time spent in flexion and extension of the wrist, as well as excessive exposure to hand vibration from the drumsticks striking the surface area (2022). All percussionists of all domains, whether in hand drumming, snare drumming, drumset playing, or four-mallet playing are exposed to these risk factors, as wrist flexion and extension is needed to play any type of vertical stroke on virtually every percussion instrument, and striking any instrument will result in some degree of vibration.

I believe that there are risk factors unique to mallet playing, which have yet to be explored in the literature. While there has not been studies to find four-mallet-specific risk factors, I can postulate what they are based on personal experience and my understanding of four-mallet technique. The first of these unique risk factors is forearm rotation (Video 1).

This technique is performed with the twisting of the the two bones that run parallel in your forearm – known as the radial and ulna bones – as the hand alternates between a pronated and semi-supinated position, (Figure 1) and is a key characteristic to playing marimba (Bissantz, 2023). The degrees of pronation and supination depend on choice of four-mallet grip, but all mallet players must execute some form of rotation to play four-mallet compositions on all keyboard percussion instruments. The percussionists control of forearm rotation is necessary when performing techniques such as double or triple lateral strokes, as well as one handed rolls, which are cornerstones within the repertoire for four-mallet vibraphone and marimba. Another element unique to four-mallet playing is interval control, which is where the mallets are ‘closed’ together or ‘spread’ apart by engagement of the fingers (Bissantz, 2023). This finger engagement changes the demands on the wrist and elbow positions, and increases tension, which increases the demands of playing mallet percussion.

Another risk factor is the amount of weight a four-mallet player must hold within their hands. A single mallet can weigh between 70-170 grams depending on make and model, and because a four-mallet player must hold two mallets in each hand, the sheer mass a percussionist must practice and perform with is certainly a significant contribution to the development of injury.

The constant utilization of these motions of flexion, extension and rotation compounded with the added mass of mallets and sticks and the repetitive nature of practice and performance create large tissue demand for percussionists; often one that will lead to injury for beginner percussionists who have not experienced these movements before.

Preventative measure: Progressive increase of practice time and incorporating break times.

Some ways that an early percussionist can reduce likelihood of injury is through progressively increasing practice time, and incorporating regular rest breaks. Lets imagine we have somebody who makes a goal of wanting to be better at push-ups. On their first day doing the exercise, they may be able to only do 3 or 4 push-ups until their body fails and they cannot execute any more. After a day of rest, they can come back and maybe add a push-up or two before they reach failure. Throughout the week of practicing these push-ups they will gain strength, muscle, and their body will execute the push-up technique easier, and after a month, they may be able to execute 20 push ups in a row. This is a very simplified example of progressive overload, which is when you expose your tissues to stimulus and make them stronger and capable for executing a desired task.

This method and mentality can be applied to percussion practice as well.

A beginner percussionist should engage in these motions for only as long as they can, and slowly increase practice time as their body becomes more accustomed to it. If you have an performance examination or major concert or recital you must prepare for, be ready to create a plan and slowly increase practice time over the course of days and weeks. The general recommendation from Watson is to increase practice time by 10-20% every week (2009). What you should not do is go from little to no practice to practicing 4+ hours a day. In the case of our aspiring push-up master, its easy to imagine what kind of acute or chronic injury they would develop if they tried going from 0 push-ups a day to consistently trying to achieve 100 push-ups in a single session.

Another recommendation is to include regular rest breaks in practice sessions. Perhaps our push-up aficionado can do 5 push-ups in a row before failing, but decides to take a small break and trying again. They may be only able to do 4 push ups on the second attempt until they fail, take another break, and then 2-3 on a third attempt. In total our aspiring push-upper has achieved 11-12 push-ups over the course of 3 attempts.

Utilizing small breaks like this to break up practice works for musicians as well. It is recommended by Klickstein (2009) to take a 10 minute break for every hour of practice. A 2024 review of preventative measures for repetitive computer work recommends a 10 minute break every hour as well as a 30-second micro break at 20 minute intervals during that hour. During the break, you can try stretching, walking around your rehearsal room or hallway, or do absolutely nothing. All of these are great ways to reduce mental and physical tension, as well as allow our tissue to recover before the next session (Klickstein, 2009).

Awareness of internal physical and mental tension during practice is also key to reducing the stress of repetition. Avoiding squeezing the sticks and mallets with your fingers, allowing fluid and relaxed motion between the wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints, and making sure that the mallet or stick bounces and ‘rebounds’ from the instrument can reduce the intensity of the time spent in flexion and extension and lessen the impact of stick vibration on the upper limb. Awareness of whole-body tension and actively working to reduce places of tension during play is a skill that, when developed, will decrease tissue demand (Klickstein, 2009).

Preventative measure: Warming up and occupation-based intervention

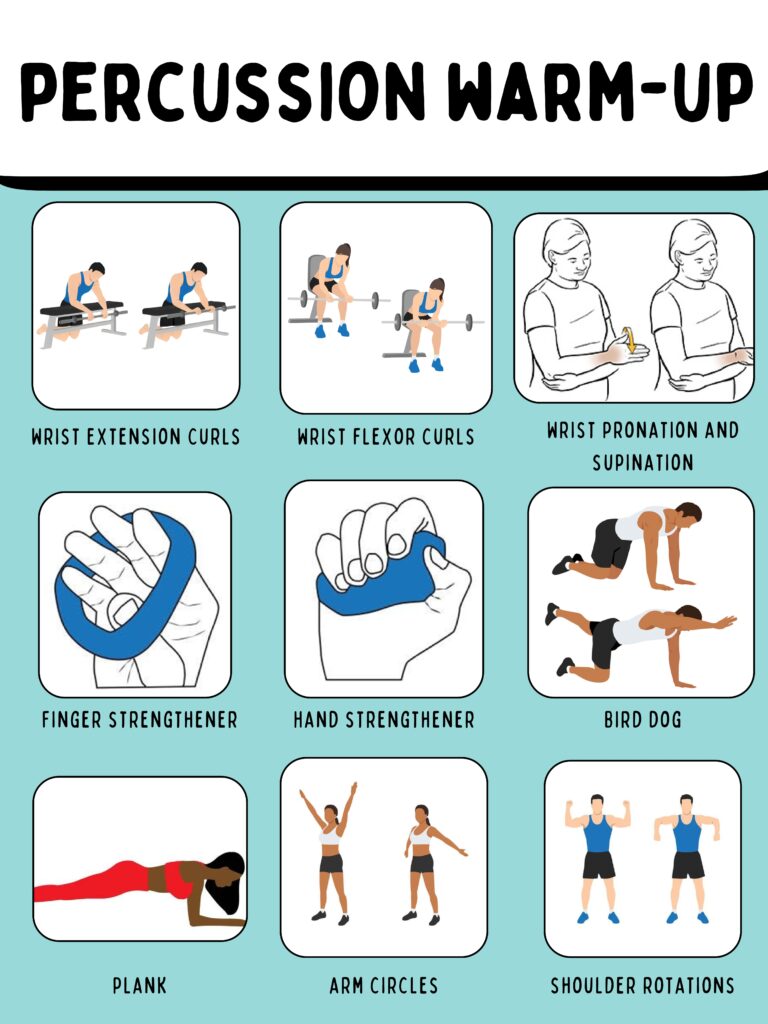

Warming up primes our tissue to handle the demands of a session of practice or a performance. For musicians, our warm ups take on the form of lighter versions of the movement we are going to engage in with the goal of reducing pain (Austen et al., 2023), activating muscles, loosen tendons and joints, and connecting our minds to our bodies in preparation of practice and performance (Klickstein, 2009). For percussionists, our warm ups can include motions like arm circles, banded finger extensions, unloaded wrist flexion and extension stretches, and unloaded forearm rotations. At the Schulich School of Music, the Applied Performance Science department’s LEAP campaign has designed a list of warm up exercises for percussionists (Figure 2).

Engaging in the exercises that are most similar to the techniques you will be playing would be helpful in preparing your body for practice. If you want to build tissue capacity faster, it may be beneficial to engage in these warm up exercises independent from your practice sessions a few times throughout a day. Lightly loaded, instrument-specific exercises such as these could be interpreted as a form of occupation-based interventions (OBI), which are interventions and exercises utilized in physical therapy for patients who have experienced injury to improve their ability in every day life.

While the efficacy of OBI in the current literature is still unclear, as there is inconsistency in the dosage and forms of OBI within the growing literature, there is enough evidence to support that there is the potential for OBI to be an effective method of building improving performance people who have experienced injury in the upper extremity (Weinstock-Zlotnick et al., 2019). OBI especially has potential in academic environments, where access to a percussion instrument may be a barrier to learning. Instruments such as the drumset, the marimba, and the vibraphone are expensive and large, and access to space and instruments is a commodity and a privilege. In a studio of percussionists who are all sharing instruments and competing for practice room time, it can be difficult to have the opportunity to spend enough time building instrument-specific tissue. Engaging in warm up exercises as OBI throughout the day is has the potential to reduce this barrier in academic environments for percussionists who have limited access to percussion instruments.

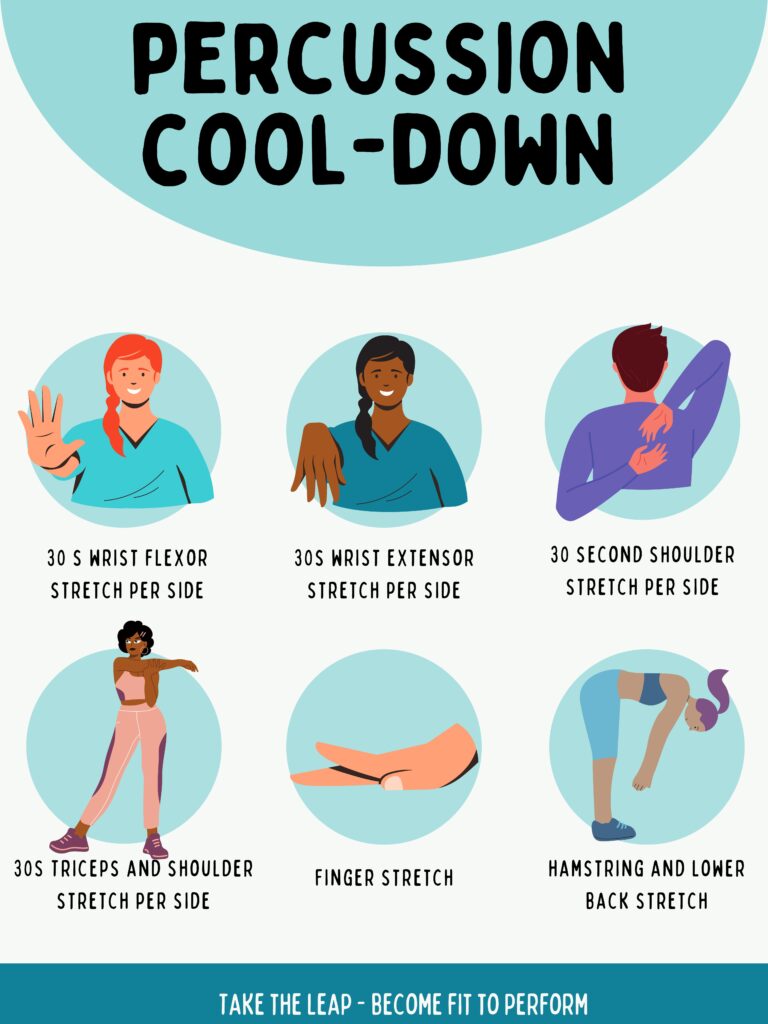

I have also included recommended exercises by the same authors that has been designed for a post-practice ‘cool down’ (Figure 3), as well as a exercise break poster (Figure 4). Utilizing this set of exercises as warm up, cool down, or OBI can all increase tissue capacity.

Risk factor: Posture

While deviations in upper-extremity posture (such as wrist flexion or extension) is necessary to play percussion, deviations in spinal posture is not. Poor posture and postural impairments is usually assumed to be associated with injury risk, but in a recent review it’s revealed there is a lack of clear evidence to definitively conclude that the two are related (Rousseau et al., 2023). Despite this, I do personally believe that poor postural alignment plays a role in injury instance in percussionists, as misalignments and asymmetrical postures put unnecessary strain on muscles which try to compensate, and these compensations can create injury over time. Percussionists still end up in positions that may contribute to injury instance, such as “…rounded shoulders, forward head, and, at equal levels, hyperextended and flat lower back” (Savvidou, 2021). It’s recommended that percussionists find their optimal posture, which is one that maintains the erect position of the vertebral column (Watson, 2009), mitigates tension, and resolves inefficiencies (Savvidou, 2021). Improving posture also improves sound quality in my experience, as well as reduce tension within the muscle, so why wouldn’t one wish to improve it?

Preventative measure: Kinesthetic awareness

The first step to first prevent postural issues is to try to become conscious of the unconscious compensations your body is making. This is referred to as kinesthetic awareness, where proprioception and the forces on our bodies are perceived by the neurons in our muscles and skin, creating a mental conception of where our bodies are in space and time (Savvidou, 2021). By being aware of the inefficiencies and tensions in your body, you are able to resolve them while playing. Keeping a short list of potential deficiencies or compensations and actively adjusting them during your practice time is recommended by Watson (2009).

Another problem with preventing postural issues is that the conception of ideal posture is not clear. Many of us have heard of Alexander technique, or are familiar with physiotherapeutic conceptions of posture, or have heard opinions from their private teachers on what optimal posture is. This creates a challenge identified by Shoebridge et al. (2017), where a student has almost too many resources and opinions on what ‘optimal’ posture is, as well as the purpose of these postural models. Are they designed for physiological optimization, or performance? In their study consisting of semi-structured interviews, Shoebridge developed an interdisciplinary theory of finding one’s optimal posture named “Minding the Body“, comprised of six subprocesses (2017). Savvidou summarizes the complex theory and the six “subprocesses” quite well as: “…finding balance within oneself and with one’s instrument, playing with minimal effort, challenging poor habits, expanding traditional understanding to improve performance, and examining barriers to improving posture” (2021). Essentially, the development of a connection between one’s mind and body is the core of developing good postural habits. By listening to your body, you will understand the postural demands, and be able to proactively create posture that is suited to the task.

Preventative measure: Instrument ergonomics

A less abstract method of improving posture is by adjusting our instruments to create an ergonomic landscape with minimal injury risk. Percussionists are fortunate in that many of our instruments are played standing, which creates compression on the spinal disks (Watson, 2009). Since the instruments we play are typically played standing, and all of our bodies are different, a simple way to improve posture is to adjust instrument height to fit your body. In these three photos, the marimba set at different heights: the preferred height, the lowest height, and the highest height (Figure 3). You can see the resultant upper extremity posture for each height varies quite a bit. These small decisions may play a major role in the development of injuries.

The decision to select a height comes from experience and feeling, and may change as your body changes. Guidelines to instrument height is to select heights that suit your body in a such a way that feels comfortable, with the least amount of whole-body tension, maintaining low shoulders, keeping even weight distribution between your feet, having your shoulders stacked above your hips, and holding a vertical neck alignment (Watson, 2009). Any instrument where you can change the height, such as snare drum, multi-percussion, or vibraphone, should have their playing surface in an area that feels good for you.

Risk factor: Life habits and physical conditioning

It is recorded by Araujo et al., that music students have poor engagement with health responsibility, stress management, poor sleep quality, and self-report low levels of health (2017). This is particularly concerning, as poor life habits and physical conditioning is recognized as a contributing risk factor to injury by Rousseau et al., (2017). Outside of music-adjacent literature, it is reported in populations of athletes, civilians, and army personnel that poorer performance in muscle endurance or cardiorespiratory endurance tests is a predictor for injury (de la Motte et al., 2017 a,b), and in one example, nutrition has significant implications for injury prevention in combat athletes (Turnagol et al., 2021). Diet is a modifiable factor so powerful that the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study finds “improvement of diet could potentially prevent one in every five deaths globally” (2017). Furthermore, poor sleep and chronic sleep disorders have been concluded by the Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research to have “…profound and widespread effects on human health” (2006).

This may seem very intense and macabre, but to put this in simpler and practical terms for percussion performance, the ‘takeaway’ is that improvements in one’s sleep quality, nutrition quality, and physical fitness will improve tissue capacity to better meet the demands of practice and performance.

So why don’t music students participate in healthier habits? The disconnect between music students and the ability to take care of health may be due to a lack of health awareness. Araujo et al., writes “Embedding and supporting health awareness as part of the curriculum, offering professional development activities on health education to instrumental teachers, and make health screening initiatives available are some examples of how specialist music education institutions can contribute to the development of healthier musicians from early ages” (2017).

Musicians may simply not know how important improving ones physical fitness, diet, and sleep quality may be.

The following uses educative preventative measures to mitigate life habits and physical conditioning as a risk factor.

Preventative measure: Diet and hydration

A proper diet is comprised of proper hydration and a balance of healthy fats, carbohydrates, vegetables, proteins, vitamins and minerals. NHS recommends consuming enough water so that your “…pee is a clear pale-yellow colour.” This allows your tendons to move more fluidly, keeps your connective tissue strong, and allows your cardiovascular system to cycle waste and nutrients through your body. For most people, this is 6-8 cups of water a day.

The average biological adult male needs 2500 calories a day, while the average biological female needs around 2000. Our caloric intake is comprised of everything we eat and drink. Fruits and vegetables should make up the most of a diet, and we should aim to eat a minimum of 5 portions of fresh, frozen, canned, dried, or juiced fruits and vegetables a day. The fresher the vegetables, the more fiber, minerals and vitamins it has, so limiting juiced fruits and vegetables in favor of solid ones is slightly healthier. The next most important group of foods to eat is starchy foods, which can fill a third of our diet. These foods include rice, grains, whole wheat breads and pastas, and potatoes. These supply our body with simple carbohydrates for energy, as well as important minerals. The next major category is proteins, which is comprised of lentils, soy, beans, eggs, meat, and fish, which can supply 10-35% of our caloric intake. These are comprised of protein, which our body can take to build muscle and repair tissue. Leaner and less processed options will be slightly healthier.

Eating well is difficult. There is no doubt about this. Do your best to cook, and if you must eat out due to school pressures or life stress, try to make choices that align with healthier habits such as increased vegetable intake, choosing whole grains, and leaner proteins with minimal salt and added sugar.

For more information on how to improve one’s diet, you can find the NHS Eatwell Guide here (NHS UK, 2022). Download it to your phone for ease of access and check on it occasionally to remind yourself what a balanced diet looks like, just in case you forget.

Preventative measure: Improving Sleep

For adults, 7-9 hours of sleep a night is recommended (NHS UK, 2025).

Deviations from sufficient sleep can be categorized as sleep deprivation, which is a lack of needed sleep, and insomnia, which is the inability to sleep. Sleep deprivation is common in musicians due to stress in life or school, relationship and social pressures, poor planning, poor sleep hygiene, or medical problems (Araujo et al., 2017). Try your best in balancing your work and social life, plan and prioritize your sleep schedule, and practice good sleep hygiene.

Savvidou gives a summary of guidelines for good sleep hygiene. These include maintaining a sleep/wake routine, respond to sleepiness cues, keeping screens and technology out of the bedroom, avoiding looking at screens about an hour before bedtime, using blue-light blocking glasses to mitigate the waking effect of screen light, dimming lights one hour before sleeping. Some other recommendations include keeping the room dark, avoiding eating a heavy meal close to bedtime, limiting alcohol and avoid caffeine intake, and exercising regularly (Savvidou, 2021).

You can check here for tips from the NHS in improving sleep.

If you are chronically struggling with poor sleep, and it is affecting your life, you may need to seek medical help. Sleep is an important part of success and the quality of work and practice will deteriorate alongside your sleep quality.

Preventative measure: Fitness

It has been shown in literature pertaining to military and athlete populations that poor cardiorespiratory endurance as well as muscular strength and endurance can be a predictor for injury in those populations (de la Motte et al., 2017 a,b.). While these populations are known for high tissue demands in their occupations, some of the literature pertaining to drummers indicates that the heart rate and calorie expenditure of a drumset player in a live can reach levels comparable to soccer players. (Azar, 2022) Therefore, it is not unreasonable to assume that improvement in general fitness can help musicians reduce their chances of injury as well.

When conceptualizing fitness, it’s easy to jump immediately to muscular body builders, MMA fighters, or marathon runners, and feel intimidated or dissuaded to go to the gym, participate in sports, or find avenues to improve physical health.

Improving physical health is not as intense as it may initially seem.

According to the NHS (NHS UK, 2024), fitness guidelines for adults are:

- do strengthening activities that work all the major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders and arms) on at least 2 days a week

- do at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity a week or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity a week

- spread exercise and activity evenly over 4 to 5 days a week, or every day

- reduce time spent sitting or lying down and break up long periods of not moving with some activity

Another potential benefit of improving the muscle and cardiovascular systems is that the improvement in efficiency of blood flow allows for better recovery by bringing nutrients to the injured tissue, and lactic acid and metabolites from the injured tissue; possibly expediting the recovery process (Romero et al., 2017) (Konopka et al., 2014). In short, there are virtually no potential downsides in improving general fitness, and quite a few potential benefits to be gained from improving ones cardiovascular and muscular fitness.

The activities you choose as exercise should be something you find enjoyable and motivating. Some ideas of activities or forms of exercise can be:

- playing squash or tennis with your friends

- going to the gym with your favorite music or podcasts

- Playing frisbee or catch with your friends

- bi-weekly cardio kickboxing classes

- weekend yoga and Pilates

- running on the school track

- a brisk walk in the local park

- an at-home bodyweight routine

One or more of these can be enough to reach your activity goals for the week. Be creative, exploratory, and channel your inner child as you seek a form of exercise that appeals to you. As long as you find something fun and consistent that you can (and want to) actively make time for, you will see improvements in your physical and mental health which will reduce the risk of injury.

“Quick fixes”. Self-massage and taping techniques

These are extra methods that you can use as a percussionist to help your personal practice. Realistically in an academic or professional musical environment, there are dates and deadlines where performances or examinations need to be prepared, and you may not have the time build the appropriate tissue capacity to meet your academic or professional obligations. Quick fixes, such as short-term recovery techniques like self massage or upper-extremity taping techniques can reduce tissue demand in scenarios when you may need help performing or practicing a lot in a small time frame.

Self-massage is a possible method of reducing pain and injury risk in the short term. In a review analyzing self massage with resistance training athletes, it was found that “self-massage provides an expedient method to promote movement efficiency and reduce injury risk by improving ROM, muscular function, and reducing pain and allows athletes to continue to train at their desired frequency with minimal disruption” (MacLennan et al., 2023). According to some literature, engaging in self-massage as a short-term recovery technique may help with issues such as lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow), carpal tunnel syndrome, and plantar fasciitis (Piper et al., 2017). Self-massage may be helpful for percussionists in their upper arm, but does not standalone as a recovery technique. Multimodal care such as diet, sleep, fitness, and rest work in conjunction with self massage. Anecdotally, through my professors and self experience, its been known that percussionists use self massage of the forearm muscles to help recover from soreness that may have developed from long practice sessions.

Taping techniques are also used in athlete and musician populations to decrease tissue demand. In a study involving violinists, taping the wrist with tape has been shown to mildly reduce pain (Topdemir et al., 2021). It has been shown that, “…taping technique, as applied in this study demonstrates an impressive effect on wrist extension force and grip strength of patients with [tennis elbow]. Elbow taping also reduces pain at the lateral aspect of the elbow in these patients” (Shamsoddini et al., 2013). Taping techniques can help avoid injury, as they allow music practice while reducing the load on the upper extremities. In a study examining the differences of force output with and without tape determined that tape has significant increase in forces exerted, as well as use in treating pain symptoms with various disorders. If you would like to apply these taping techniques yourself, in her article she includes short videos where she walks you through on how to properly tape the wrist for specific disorders. These can be found here (Porretto-Loehrke et al., 2016).

Conclusion

The prevention of injury is a long-term process of managing risk factors, increasing tissue capacity and decreasing the demand of percussion performance. Awareness of risk factors through education as well as consciously trying to understand and employ healthy life habits will hopefully reduce the risk of injury in early players. Injury prevention is the first step, and enabling educators and students to feel empowered to teach and learn preventative measures will create a future where beginner percussionists can avoid assessment and therapy, saving time, money, and stress and allowing the culture of percussion to grow. Hopefully this blog has given you an opportunity to learn a little more about the potential risk factors you may have faced as a percussionist, and inspired you to see where you can incorporate some preventative measures into your life as a musician.

Bibliography

Araújo, L. S., Wasley, D., Perkins, R., Atkins, L., Redding, E., Ginsborg, J., & Williamon, A. (2017). Fit to perform: An Investigation of higher education music students’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward health. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01558

Austen, C., Redman, D., & Martini, M. (2024). Warm-up exercises reduce music conservatoire students’ pain intensity when controlling for mood, sleep and physical activity: A pilot study. British Journal of Pain, 18(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/20494637231188306

Bass, E. (2012). Tendinopathy: why the difference between tendinitis and tendinosis matters. International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork, 5(1), 14–17. https://doi.org/10.3822/ijtmb.v5i1.153

Bissantz, K. S. (2023). Get a grip: An anatomical survey of four-mallet grips for solo marimba. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 4816. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/36948166 https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2009.1007.

Brandfonbrener, A. G. (2009). History of playing-related pain in 330 university freshman music students. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(1), 30–36.

Braun-Trocchio, R., Graybeal, A. J., Kreutzer, A., Warfield, E., Renteria, J., Harrison, K., Williams, A., Moss, K., & Shah, M. (2022). Recovery strategies in endurance athletes. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 7(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk7010022

Chan, C., & Ackermann, B. (2014). Evidence-informed physical therapy management of performance-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00706

Cheuquelaf-Galaz, C., Antúnez-Riveros, M. A., Lastra-Millán, A., Canals, A., Aguilera-Godoy, A., Núñez-Cortés, R., (2024). Exercise-based intervention as a nonsurgical treatment for patients with carpal instability: A case series. Journal of Hand Therapy, 37(3), 397-404, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2023.08.010.

Cunningham, Susan. (2025, March 31). Rest and recovery are critical for athletes of all ages from students to pros to older adults. UC Health Today. https://www.uchealth.org/today/rest-and-recovery-for-athletes-physiological-psychological-well-being/

de la Motte, S. J., Gribbin, T. C., Lisman, P., Murphy, K., & Deuster, P. A. (2017). Systematic review of the association between physical fitness and musculoskeletal injury risk: Part 1—cardiorespiratory endurance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(6), 1744-1757. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001855.

de la Motte, S. J., Gribbin, T. C., Lisman, P., Murphy, K., & Deuster, P. A. (2017). Systematic review of the association between physical fitness and musculoskeletal injury risk: Part 2-muscular endurance and muscular strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(11), 3218–3234. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002174.

de Waal, A., Killian, A., Gagela, A., Baartzes, J., de Klerk, S. (2024) Therapeutic approaches for the prevention of upper limb repetitive strain injuries in work-related computer use: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10204-z.

Dupuy, O., Douzi, W., Theurot, D., Bosquet, L., & Dugué, B. (2018). An evidence-based approach for choosing post-exercise recovery techniques to reduce markers of muscle damage, soreness, fatigue, and inflammation: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00403

Foxman, I., & Burgel, B. J. (2006). Musician health and safety: Preventing playing-related musculoskeletal disorders. AAOHN journal : Official journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, 54(7), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507990605400703.

GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators (2019). Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England), 393, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

Iglesias-Carrasco, C., de-la-Casa-Almeida, M., Suárez-Serrano, C., Benítez-Lugo, M. L., & Medrano-Sánchez, E. M. (2024). Efficacy of therapeutic exercise in reducing pain in instrumental musicians: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare, 12(13), https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131340.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. (2006). Extent and health consequences of chronic sleep loss and sleep disorders. H.R. Colten, B.M. Altevogt, (Eds.), Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: An Unmet public health problem. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19961/

Klickstein, G. (2009). The musician’s way : A guide to practice, performance, and wellness (1st ed). Oxford University Press.

Konopka, A. R., & Harber, M. P. (2014). Skeletal muscle hypertrophy after aerobic exercise training. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 42(2), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000007

Li, S., Kempe, M., Brink, M., & Lemmink, K. (2024). Effectiveness of recovery strategies after training and competition in endurance athletes: An umbrella review. Sports Medicine – open, 10(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00724-6.

Lysyk, T. (2025), Figure 1, Example of pronated and supinated arm position.

Lysyk, T. (2025), Figure 3, Marimbist at three different heights.

Lysyk, T. (2025), Video 1, Example of forearm rotation.

MacLennan, M., Ramirez-Campillo, R., & Byrne, P. J. (2023). Self-massage techniques for the management of pain and mobility with application to resistance training: A Brief review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 37(11), 2314–2323. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004575.

Matei, R., & Ginsborg, J. (2020). Physical activity, sedentary behavior, anxiety, and pain among musicians in the united kingdom. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.560026.

Merriam-Webster. Risk factor. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/risk%20factor

NHS UK. (2024, May 22). Physical activity guidelines for adults aged 19 to 64. NHS UK Live Well, Exercise. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/physical-activity-guidelines-for-adults-aged-19-to-64/

NHS UK. (2023, May 17). Water, drinks and hydration. NHS UK Live Well, Eat Well, Food Guidelines and Food Labels. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/water-drinks-nutrition/

NHS UK. (2022, November 29). The Eatwell Guide. NHS UK Live Well, Eat Well, Food Guidelines and Food Labels. The Eatwell Guide – NHS

NHS UK. (2025). How to fall asleep faster and sleep better. NHS Every Mind Matters, Mental wellbeing tips. Fall asleep faster and sleep better – Every Mind Matters – NHS

Ortiz, R. O., Jr, Sinclair Elder, A. J., Elder, C. L., & Dawes, J. J. (2019). A systematic review on the effectiveness of active recovery interventions on athletic performance of professional-, collegiate-, and competitive-level adult athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning research, 33(8), 2275–2287. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002589.

Piper, S., Shearer, H. M., Côté, P., Wong, J. J., Yu, H., Varatharajan, S., Southerst, D., Randhawa, K. A., Sutton, D. A., Stupar, M., Nordin, M. C., Mior, S. A., van der Velde, G. M., & Taylor-Vaisey, A. L. (2016). The effectiveness of soft-tissue therapy for the management of musculoskeletal disorders and injuries of the upper and lower extremities: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration, Manual Therapy, 21, 18-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.08.011.

Porretto-Loehrke, A. (2016). Taping techniques for the wrist, Journal of Hand Therapy, 29(2), 213-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2016.03.002.

Romero, S. A., Minson, C. T., & Halliwill, J. R. (2017). The cardiovascular system after exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 122(4), https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00802.2016.

Rousseau, C., Barton, G., Garden, P., Baltzopoulos, V. (2021). Development of an injury prevention model for playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in orchestra musicians based on predisposing risk factors. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2020.103026.

Rousseau, C., Taha, L., Barton, G., Garden, P., Baltzopoulos, V. (2023). Assessing posture while playing in musicians – A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103883.

Sandell, C., Frykman, M., Chesky, K., & Fjellman-Wiklund, A. (2009). Playing-related musculoskeletal disorders and stress-related health problems among percussionists. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(4), 175-180, https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2009.4035.

Savvidou, P. (2021). Teaching the whole musician: A guide to wellness in the applied studio. Oxford Academic. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1093/oso/9780190868796.001.0001.

Shamsoddini, A., & Hollisaz, M. T. (2013). Effects of taping on pain, grip strength and wrist extension force in patients with tennis elbow. Trauma monthly, 18(2), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.5812/traumamon.12450.

Shoebridge, A. S., Nora & Webster, K. (2017). Minding the body: An interdisciplinary theory of optimal posture for musicians. Psychology of Music. 45. http://doi.org/10.1177/0305735617691593.

Topdemir, E., Tansu Birinci, T., Taşkıran, H., Mutlu, E. K. (2021). The effectiveness of Kinesio taping on playing-related pain, function and muscle strength in violin players: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Physical Therapy in Sport, 52, 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2021.08.010.

Turnagöl, H. H., Koşar, Ş. N., Güzel, Y., Aktitiz, S., & Atakan, M. M. (2021). Nutritional considerations for injury prevention and recovery in combat sports. Nutrients, 14(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14010053.

Watson, A. H. D. (2009). The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury. Scarecrow Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10364505.

Wang, L., Rilling, A. (2023). Percussionist warm up poster.

Wang, L., Rilling, A. (2023). Percussionist cool down poster.

Wang, L., Rilling, A. (2023). Musician exercise break poster.

Weinstock-Zlotnick, G., & Mehta, S. P. (2019). A systematic review of the benefits of occupation-based intervention for patients with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Hand Therapy, 32(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2018.04.001

Weakley, J., Broatch, J., O’Riordan, S., Morrison, M., Maniar, N., & Halson, S. L. (2022). Putting the squeeze on compression garments: Current evidence and recommendations for future research: A systematic scoping review. Sports Medicine, 52(5), 1141–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01604-9.

Yang, S. W., & Choi, J. B. (2024). Effects of kinesio taping combined with upper extremity function training home program on upper limb function and self-efficacy in stroke patients: An experimental study. Medicine, 103(30), https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000039050.