Take a look around the violin or viola sections of an orchestra and you will see that there are a plethora of ways in which violinists have ‘set up’ their instruments. You will observe different kinds of chin rests, some tall, some short, some in the center, some on the side. You may also notice that some have nothing supporting their instruments from underneath, whereas others have shoulder rests of different shapes and sizes. Some have foam wrapped around their shoulder rest with rubber bands, some have sponges that seem to stick to the instrument, etc. With all of these options, how is a violinist to find their personal ‘set-up’? Is there a formula?

Take a look around the violin or viola sections of an orchestra and you will see that there are a plethora of ways in which violinists have ‘set up’ their instruments. You will observe different kinds of chin rests, some tall, some short, some in the center, some on the side. You may also notice that some have nothing supporting their instruments from underneath, whereas others have shoulder rests of different shapes and sizes. Some have foam wrapped around their shoulder rest with rubber bands, some have sponges that seem to stick to the instrument, etc. With all of these options, how is a violinist to find their personal ‘set-up’? Is there a formula?

Musculoskeletal pain is experienced in up to 80% of professional musicians (Steinmetz, 2016). There is a higher percentage of upper-extremity injuries in string players, because of the increased use of these muscles in string playing. Having a comfortable set up and technique is paramount to avoiding injury and to playing with ease. Also, with less tension present in the player, the instrument becomes more resonant.

Many violinists accept their set-up from what their teacher taught them when they started violin. However, if you anticipate that you’ll be playing violin for a long while, you may want to question your set-up, especially if you feel discomfort when playing, or if you feel that your technique is being inhibited by tension in the neck and shoulders.

How does our brain control our posture and violin hold?

Postural stance is integral to violin hold; it serves as a foundation for freeing up the motions of the shoulders and arms. One’s stance should be stable, meaning that the body’s center of mass is directly over the feet. Rotation movements in the hips and ankles control the body’s mass and keep it above the feet (Latash 2006). If you want to find out more about the foundations of one’s postural stance when holding violin or viola, visit this page.

Postural stance is integral to violin hold; it serves as a foundation for freeing up the motions of the shoulders and arms. One’s stance should be stable, meaning that the body’s center of mass is directly over the feet. Rotation movements in the hips and ankles control the body’s mass and keep it above the feet (Latash 2006). If you want to find out more about the foundations of one’s postural stance when holding violin or viola, visit this page.

One must keep this in mind when trying new set-ups and working on comfortable technique. Posture is your foundation! Without a steady base, the arms and fingers cannot function with accuracy and ease. If you are working on your technique or switching your set up, realize that it takes mindful thought when learning a new body-pattern. And it is much more difficult if you are changing an old habit—so be persistent!

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”Motor Cortex” state=”opened”]

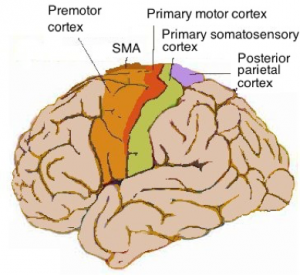

In using the body, our motor cortex, located at the back of the frontal lobe of the brain, commands the muscles to move. The motor cortex has plasticity, which means that the neurological pathways in the brain can strengthen or weaken depending on how it is used. When one learns a new task, the motor cortex activity in the brain increases (Latash 2006). However, after time passes, the learning consolidates and it does not take as much thought (Latash, 2006).

In using the body, our motor cortex, located at the back of the frontal lobe of the brain, commands the muscles to move. The motor cortex has plasticity, which means that the neurological pathways in the brain can strengthen or weaken depending on how it is used. When one learns a new task, the motor cortex activity in the brain increases (Latash 2006). However, after time passes, the learning consolidates and it does not take as much thought (Latash, 2006).

“Consolidation is the process whereby learned skills become more permanent. Immediately after learning, the motor memory is fragile. In particular, it is vulnerable to disruption by learning of something similar. However, if there is no disruption, with the passage of time, the memory becomes more robust. It is this process, of becoming more robust with time, that is designated consolidation” (Latash, 2006)

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”The Spine”]

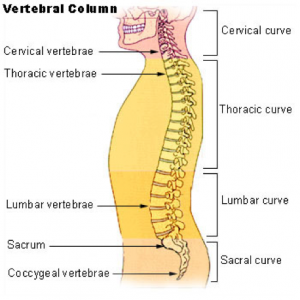

A study of the anatomical differences in violin players versus non-musicians showed that violinists had a “higher body mass and deeper and longer thoracic kyphosis, which in turn showed decreased angle of lumbar lordosis” (Barczyk-Pawelec, 2012).

This is a diagram of the sections of the spine; as you can see, the spine contains natural curves. Kyphosis is when the spine curves outward more than natural. Lordosis is when the spine is curved inward more than natural. Therefore, the thoracic kyphosis would the thoracic curve overly curved outwards, and lumbar lordosis would be the lumbar curve overly curved inwards.

Playing violin can change the shape of our spine. Our body adapts to what we do. However, we want to ensure we are supporting the spine and keeping its curve in alignment. One way to make sure the posture is in proper alignment is to slightly bend the knees (Lieberman 2010). Our muscles support our spine; we should engage our abdominal wall in standing or sitting to keep this support against the pull of gravity.

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”The Neck”]

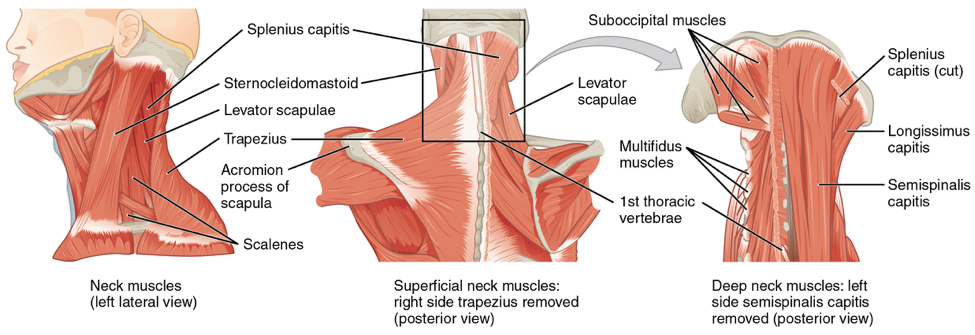

Common to the average person with neck pain, violinists with neck pain had increased activity of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which is associated with less activity in the deep neck flexor muscles (Steinmetz, 2016).

Therefore, we want to find a violin set-up that uses the deep neck flexor muscles and not the superficial ones, so as not to cause excessive neck tension, and therefore, neck pain. See above, the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which is superficial, and when overused causes neck pain. On the right are the deep neck muscles, that should be used when holding the violin. We want to avoid overly “clamping” on the instrument, which will tire the neck muscles, rather, we want to find a proper set up that supports the instrument with minimal pressure from the neck.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

What to Keep in Mind

The goals of one’s set-up:

- Minimal tension in neck and shoulders (Lieberman, 2010)

- Natural octave frame in the left hand, so that all fingers have maximum power (Galamian, 1962) (practice ‘hammering’ the string with the fingers of the left hand to test their power)

- Bow angle is ideal for a straight bow (shorter people may need to point the violin more inwards in order to reach the tip of the bow)

- At approximately the middle of the bow, arm and instrument should form a ‘square’ (Galamian, 1962)

The four planes that you can change (according to Lieberman, in her DVD entitled Violin and viola ergonomics):

- Vertical plane (changed by height of shoulder/chin rest combinations)

- Horizontal plane (if the violin is pointing forwards or to the side of the body)

- Angle (of scroll)

- Tilt (how the violin is tilted)

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”Chin-rest or Jaw-rest?” state=”opened”]

In the violin set-up, it is important that the jaw bone and the collarbone balance the instrument. There is a misconception that the chinrest should be held with the chin; rather, the jaw bone should rest on the chinrest, and that will provide much more support with much less tension. This frees the motion of the left shoulder and arm. The neck and shoulder muscles must not overly clamp down on the instrument, rather, the violin should feel supported by the balance in between the jaw bone and the collarbone and (depending on your training) the left hand (Lieberman, 2010).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Role of the Left Hand”]

There are different approaches to the role of the left hand. Some teachers emphasize that the left hand fully supports the instrument. Other teachers emphasize the chin/jaw holding the instrument without any help of the left hand (many young students learn to hold the instrument this way, by dropping the left arm by their side to ensure the violin is still being held up). And many are somewhere in between these two, balance in the left hand, and support from the jaw especially when the left hand has shifts.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Experiment: What are the Options?

Find placement mixing and matching with these options. There are many options to choose from!

[tabs]

[tab title=”Chinrests”]

Side Chinrest Centre Chinrest In between side and centre

- Tall or Short

- Centre or Side

[/tab]

[tab title=”Shoulder Rests”]

- There are many shapes and sizes of shoulder rests. Most have adjustable “feet” that raise and lower.

- You can adjust the distance from foot to foot.

- Experiment with the angle of the shoulder rest on the instrument itself as that will change the horizontal plane (Lieberman, 2010).

[/tab]

[tab title=”No Shoulder Rest”]

- Many violinists do not use a shoulder rest at all.

- You can use pads/leather/etc to hold the instrument on the body without slipping.

- The acoustagrip is an example of a sponge padding that is placed on the back of the instrument.

- Some use a sponge placed under the shirt to create extra padding.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Fiddler’s Neck/Violin Hickey”]

Side note: to minimise the ‘fiddler’s neck’ or ‘violin hickey’ (mark on a violinist’s neck from prolonged contact with the instrument), one can place a cloth on the chinrest, or use a stradpad (a cushy pad placed over the chinrest – this creates height, so keep that in mind when sizing your set-up).

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”The Great Violin Debate – Shoulder rest or no shoulder rest?” state=”opened”]

Violinists have many different opinions on this issue! Some teachers require their new students to discard their shoulder rest and rebuild their technique from scratch. Others believe that whatever suits the player’s body is best.

Arguments against the shoulder rest: Better sound, more resonance, more natural tone and shifts because of how the body works with the instrument. (See ‘further reading’ below for stories/information from professional violinists on this topic).

Arguments for the shoulder rest: Freedom of the left hand, facilitates quick passages and shifting with extra support, those with long necks require the support in order to not drop the violin.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Advice

- Seek out help from your teacher: If your teacher is sensitive to the human body, they will often be able to recognize tension even if you don’t realize it is there. Ask multiple teachers if possible; have them watch you try some different set-ups.

- Seek out help from a physiotherapist, occupational therapist, or someone knowledgeable in ergonomics for musicians. Play and have them asses your posture.

- If you are a teacher: have options available for students to try. Keep a few shoulder rests and chinrests that your students can try. Buy a ‘chinrest’ tool, so that you can change chinrests easily (using a pencil or pen can be a pain).

- Give each change that is comfortable enough time to settle. Keep track of how long you tried each change and what the change was. As long as it does not cause pain or discomfort and you think it’s a viable option, you could try it for a few days of practice.

- Be aware of your technique. In order to find your set-up, you must try to play with relaxed shoulders and neck. Do not play through pain!

- Finding a set-up that is good for your body type will not “solve” excessive muscular tension you may be used to playing with (Lieberman 2010). You must still continue to develop a technique that allows you to play with ease.

- It is a process and a journey. Give yourself grace and patience; trust that your comfort and ease of technique will advance your musicianship immensely.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Further Reading” state=”opened”]

Article by Tim Homfray in the Strad:

http://www.thestrad.com/the-pros-and-cons-of-using-a-shoulder-rest/

Quote from the article: “Adults buying a rest can still go wrong, says Colyer. ‘When people try out rests, they have this idea that you have to be able to hold the violin with the head while the arm hangs down at the side. But that isn’t a real playing situation. The shoulder girdle is in a completely different situation when you are in playing mode, so if you try the rest by dropping your arm you’re probably feeding into a habit of gripping the violin and excessively raising the left shoulder.’”

Blog post written by Nathan Cole, First Associate Concertmaster of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

http://www.natesviolin.com/ditched-shoulder-rest-30-years/

Interview with Aaron Rosand on violinist.com

http://www.violinist.com/blog/laurie/20148/16066/

Presentation by Jonathan Swartz, professor of violin at Arizona State University

http://stringpedagogy.com/members/volumes/articles/rest_no_more.htm

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”References”]

Altenmüller, E., Kesselring, J., & Wiesendanger, M. (2006). Music, motor control, and the brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barczyk-Pawelec, K., Sipko, T., Demczuk-Włodarczyk, E., & Boczar, A. (2012). Anterioposterior spinal curvatures and magnitude of asymmetry in the trunk in musicians playing the violin compared with nonmusicians. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 35, 4, 319-326. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.04.013

Chan, R. F. M., Chow, C., Lee, G. P. S., To, L., Tsang, X. Y. S., Yeung, S. S., & Yeung, E. W. (2000). Self-perceived exertion level and objective evaluation of neuromuscular fatigue in a training session of orchestral violin players. Applied Ergonomics, 31, 4, 335-341. PII: S0003-6870(00)00008-9

Galamian, I. (1962). Principles of violin: Playing & teaching. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

Latash, M. L., & Lestienne, F. (2006). Motor control and learning. New York: Springer.

Lieberman, J. L. (2010). Violin and viola ergonomics. Winona, Minn.: Hal Leonard Studio.

Park, K. (2012). Comparison of electromyographic activity and range of neck motion in violin students with and without neck pain during playing. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 27, 4, 188-92.

Rolland, P., & University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (1970). Establishing the violin hold. Urbana, Ill.: Motion Picture Service, University of Illinois [producer.

Rosenblum, S., & Josman, N. (2003). The relationship between postural control and fine manual dexterity. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 23, 4, 47-60. DOI: 10.1080/J006v23n04_04

Steinmetz, A., Claus, A., Hodges, P. W., & Jull, G. A. (2016). Neck muscle function in violinists/violists with and without neck pain. Clinical Rheumatology: Journal of the International League of Associations for Rheumatology, 35, 4, 1045-1051. DOI 10.1007/s10067-015-3000-4

Images

AcoustaGrip Soloist, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AcoustaGrip_Soloist.jpg

Boxwood violin chinrest, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boxwood_violin_chinrest.jpg

Coussin2, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coussin2.JPG

Guarneri chinrest, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guarneri_chinrest.jpg

Human motor cortex, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Human_motor_cortex.jpg

Illu vertebral column, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Illu_vertebral_column.jpg

Posterior and Side Views of the Neck, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1111_Posterior_and_Side_Views_of_the_Neck.jpg

Vancouver Symphony Orchestra with Bramwell Tovey, via Wikimedia Commons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Vancouver_Symphony_Orchestra_with_Bramwell_Tovey.jpg

ViolinChinRest-pjt, via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ViolinChinRest-pjt.JPG

3 fiddlers in silhouette, via Wikimedia Commons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:3_fiddlers_in_silhouette.svg

[/toggle]

[/accordion]