- “My throat is strained, making my voice hoarse like a lump is in it. “

- “I lost my vocal range and cannot sing as high/low as usual. ”

- “After singing, the muscles around my throat are tight and even ache. ”

- “Even though I tried hard to open up my voice, the sound is always weak and airy. ”

- “After singing, the muscles around my throat are tight and even ache. ”

- “I lost my vocal range and cannot sing as high/low as usual. ”

Everyone may have the experience of singing in the bathroom and enjoying their voice. The voice generator larynx is delicate, and carelessness will lead to discomfort and even illness. Singing is a complex process that uses our whole body as an instrument and involves multiple muscles. All levels of singers may face a tight throat, especially in high pitches, and learning more about phonation tension can help us to avoid voice disorders and protect the throat.

In this article, we focus on introducing muscle tension dysphonia, one of the most common voice disorders. About 10% of general people have voice disorders, and among voice professionals, the proportion reaches close to 50% (Angelillo et al., 2009; Roy et al., 2004). A large number of voice disorders patients suffer from muscle tension dysphonia, and women patients are almost twice as compared to men. About 41% of professional voice users, such as vocal performers (actors, singers) and teachers, have muscle tension dysphonia (Van Houtte et al., 2010).

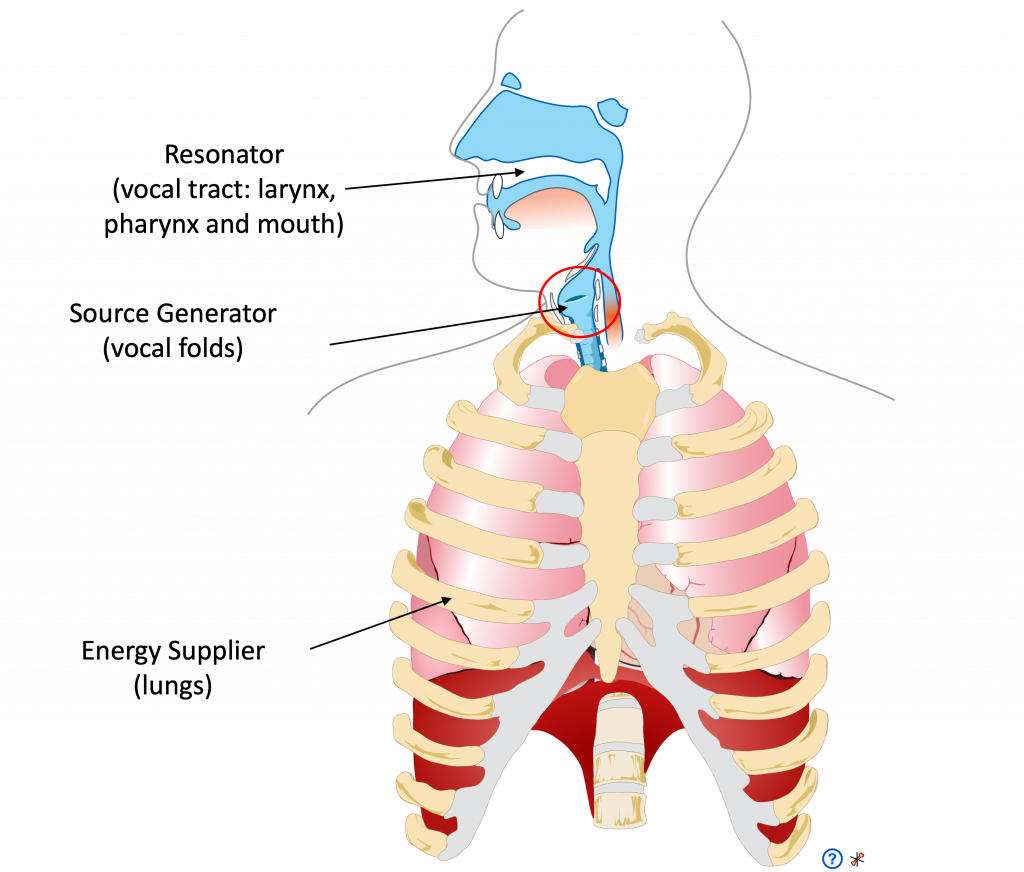

How do we generate sounds?

Voice production requires an energy supplier (lungs), a voice source generator (vocal folds), and a resonator (vocal tract). We can imagine the lungs as a spherical balloon with air inside and a whistle as the vocal folds inserted in the mouth of the balloon. When we squeeze the balloon, the whistle will make a sound. Similarly, the vocal tract is like the wood body of a guitar which helps to amplify and broadcast the sound into the air.

First, the vocal folds are closed and an airstream is issued from the lungs. The pressure difference increases between the inside and outside of the vocal folds, which will cause the vocal folds to part. Then, the air passing between the folds generates a force that almost immediately closes the vocal folds. Last, the pressure differential forces the vocal folds apart again. The process of voice generation is the continuous opening (fold adduction) and closing (fold abduction) of the vocal folds, which feeds a train of air pulses into the vocal tract (Sundberg, 1989).

Breathing and laryngeal are physiologically interdependent: the larynx is the gatekeeper of the lungs, and the pressure from the breathing apparatus provides the energy for the vocal folds to vibrate (Sundberg, 1977). A healthy phonation process, that is, the process of generating voice, needs the appropriate coordination of the respiratory and larynx apparatus.

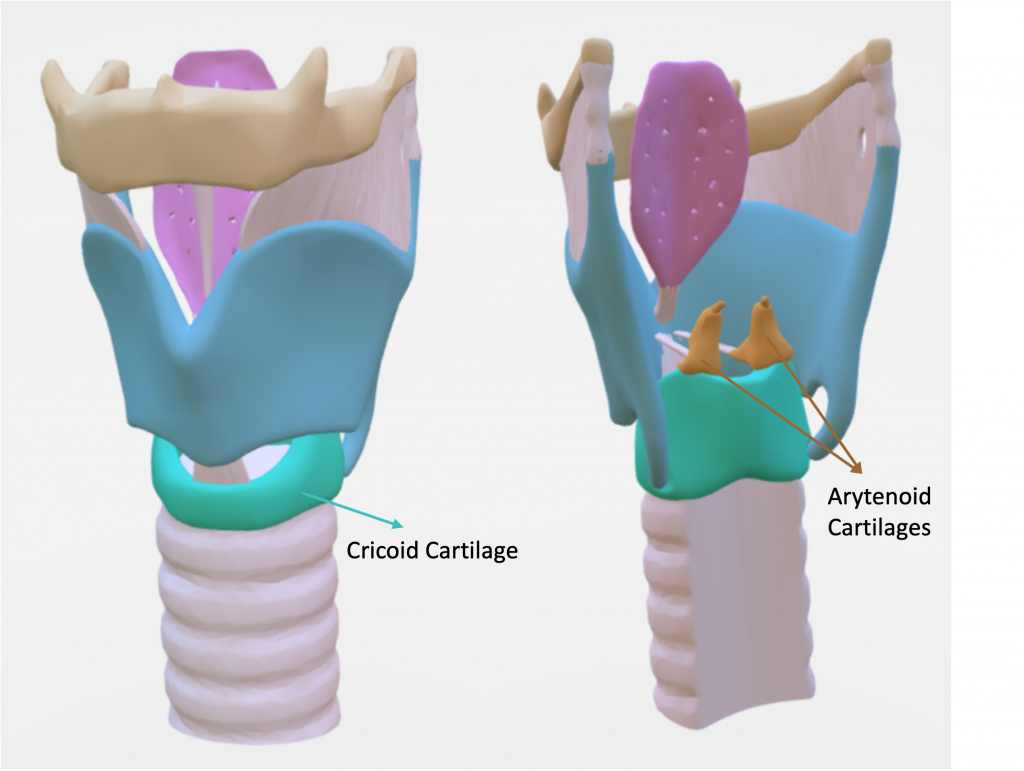

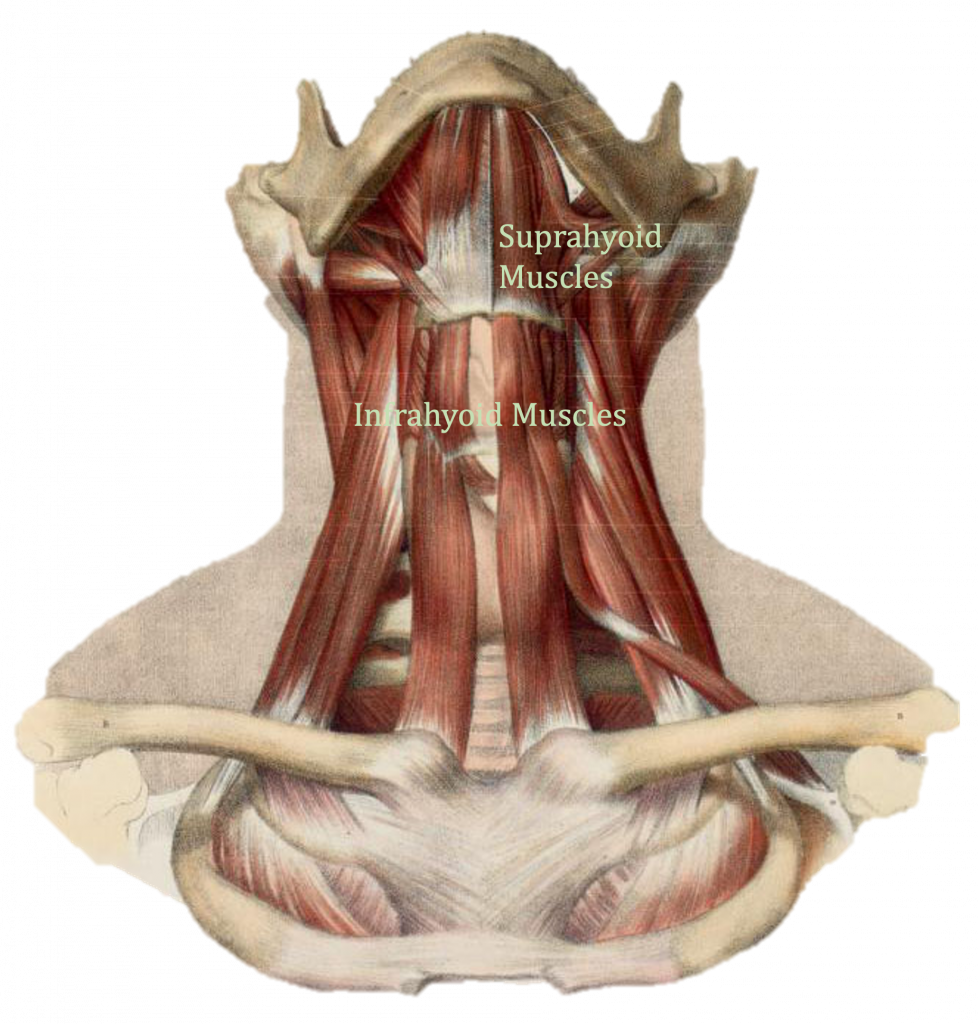

What are the muscles used in phonation?

The laryngeal muscles produce the movements of the larynx and its cartilages, protect the airways, and enable the voice to properly generate and propagate (Norton & Netter, 2012). Small intrinsic laryngeal muscles are responsible for the movement of arytenoid cartilages and thus for vocal folds opening and closing and tension. The larger extrinsic musculature (suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles) maintains the larynx in a stable and natural position so that the intrinsic laryngeal musculature can contract freely.

The main muscles involved in the singing process are

| Cricothyroid | Increase tension on vocal ligaments (increase the pitch) |

| Thyroarytenoid | Decrease tension on vocal ligaments (decrease the pitch) |

| Posterior cricoarytenoid | Open rima glottidis (abduction) |

| Lateral cricoarytenoid, transverse arytenoid, oblique arytenoid | Close rima glottidis (adduction) |

| Aryepiglotticus and thyroepiglotticus | Help close laryngopharyngeal opening |

What about voice disorders?

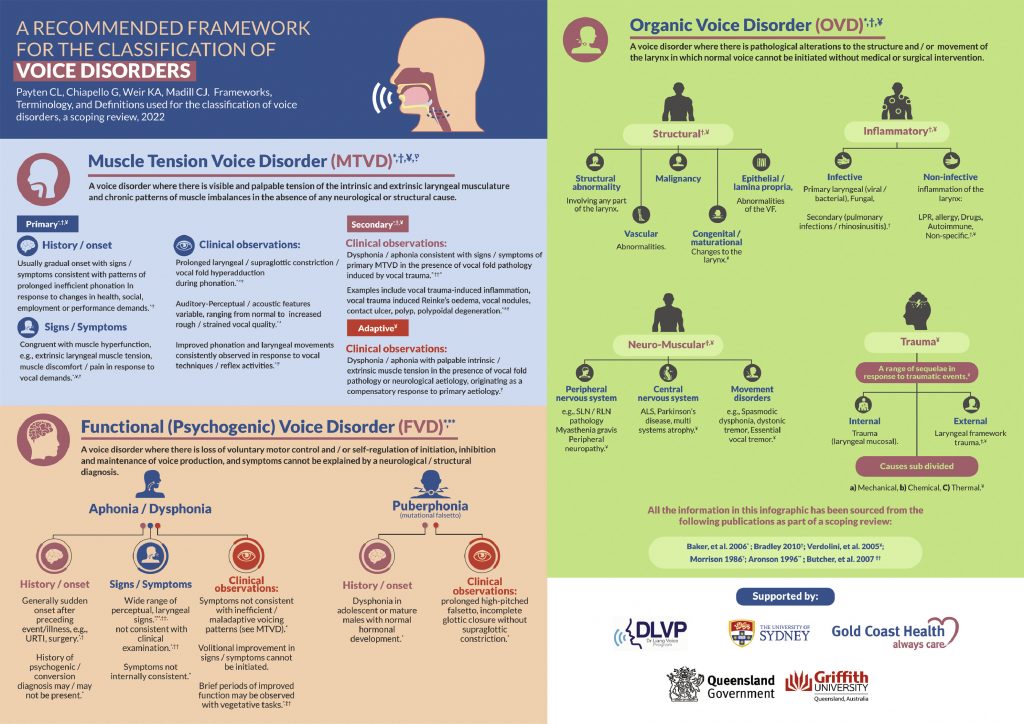

The term “voice disorder” embodies many different conditions with signs and symptoms that may occur in isolation or in combination with each other (Payten et al., 2022). Voice disorder is typically a problem of vocal folds not closing well, not vibrating well, or not vibrating symmetrically. In addition, it is generally characterized by an abnormal pitch, loudness, and vocal quality resulting from a disordered laryngeal, respiratory, and/or vocal tract functioning.

Different levels of voice disorders range from mild hoarseness to complete voice loss (Ramig & Verdolini, 1998). The nomenclature and classification of voice disorders remain controversial and problematic because many terms are used indiscriminately, interchangeably, or without clear definitions. A commonly used voice disorders classification method is the Diagnostic Classification System which classifies voice disorders into two main distinct groups: functional voice disorders and organic voice disorders (Baker et al., 2007).

Terms explanation:

Aphonia is the loss of the ability to vocalize; the patient talks only in a whisper. Dysphonia denotes impairment with hoarseness but without complete loss of function (Oyebode, 2018).

[tabs]

[tab title=”Organic Voice Disorder“]

Organic voice disorder is aphonia or dysphonia due to

- a physical wrong with the voice mechanism, involving structural changes to the vocal folds, surrounding tissues, or fluids;

- an interruption to neurological innervations of the laryngeal mechanism, in other words, when something is wrong with the part of the nervous system which controls the voice.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Functional Voice Disorder“]

A functional voice disorder is an aphonia or dysphonia where the physical structure is normal, but it uses the voice mechanism improperly. There are mainly two branches of functional voice disorders: psychogenic voice disorders and muscle tension voice disorders.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Functional – Psychogenic Voice Disorder“]

Psychogenic Voice Disorder is aphonia or dysphonia that occurs because of disturbed psychological processes (e.g., stress conversion reaction, personality disorders) or intermittent loss of volitional control over the initiation and maintenance of phonation in the absence of structural or neurological pathology sufficient to account for the dysphonia. Symptom incongruity and reversibility may be demonstrated, and psychosocial factors are often linked to onset. Whilst muscle tension patterns may be inferred or observed, such patterns are secondary to the psychological processes operating (Baker et al., 2007).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Functional – Muscle Tension Voice Disorder“]

Muscle Tension Voice Disorder is a dysphonia that develops gradually because of disturbed psychological processes that lead to chronic patterns of misuse of the laryngeal muscles. Over time these wrong vocal behaviors may lead to the development of secondary organic changes, such as vocal nodules, that are generally amenable to resolution with modification to vocal use, misuse, or abuse patterns. Psychological factors may play a role in the patterns of onset or aggravation of the dysphonia, they may appear to be secondary to the vocal trauma produced by vocal behavior patterns (Baker et al., 2007).

[/toggle]

[/tab]

[/tabs]

What is muscle tension dysphonia?

Muscle tension dysphonia is caused by muscular hyperfunction that leads to an abnormal laryngeal posture, mostly a higher laryngeal position with a certain degree of glottic and/or supraglottic compression (Van Houtte et al., 2011). All of this affects the position and inclination of the cartilaginous structures and therefore the intrinsic laryngeal musculature and the tension of the vocal folds that affect the voice and, sometimes, give rise to a sensation of tickling, dryness, irritation, or obstruction in the throat (de Alvear et al., 2010; Torabi et al., 2016).

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Signs and symptoms“]

Hyper functional phonation is characterized by excessive phonatory effort. The muscle effort involved can be apparent throughout the vocal tract so that the articulatory muscles, the extrinsic and intrinsic laryngeal muscles, and the size and shape of the resonators are affected. This vocal behavior places undue physical stresses on the anatomy and physiology of the vocal tract, causing undesirable changes in its function and, in some cases, trauma to the vocal folds. (Fernández et al., 2020)

According to a 30-months review of muscle tension dysphonia patients(Altman et al., 2005), as the below graphs show, most MTD patients will experience hoarseness. After speech pathology assessment, some clinical findings also show that most of the patients have poor breath support, inappropriate pitch, and visible cervical tension.

Voice Discomfort that Patients Complained

Clinical Findings in Speech Assessment

| Voice Discomfort | Portion |

| Hoarseness | 83% |

| Vocal fatigue | 26% |

| Vocal strain | 23% |

| Pain on or after phonation | 17% |

| “Tightness” in the throat | 11% |

| Voice loss | 9% |

| Unable to project voice | 5% |

| Globus | 5% |

| Clinical Findings | Portion |

| Poor breath support | 98% |

| Inappropriate (low) pitch | 79% |

| Cervical tension visible | 70% |

| Fast rate of speech | 21% |

| Glottal fry | 20% |

| Inappropriate (low) intensity | 14% |

| Inappropriate (high) intensity | 9% |

| Hard glottis attack | 7% |

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Diagnosis“]

The diagnosis of MTD is mainly based on the patient’s clinical history and a careful examination of the vocal folds. First, examination by a speech-language pathologist is very important in the diagnosis of muscle tension dysphonia through trial voice therapy techniques and acoustic and aerodynamic measurements. Then, using flexible laryngoscopy, they can observe some muscular patterns during speaking, and using a stroboscope allows the examiner to assess the mucosal wave as a marker for vocal fold vibration. (Garaycochea et al., 2019)

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Different types of Muscle Tension Dysphonias“]

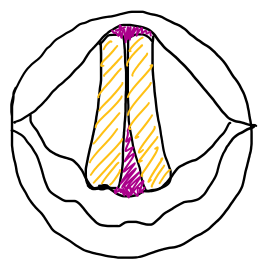

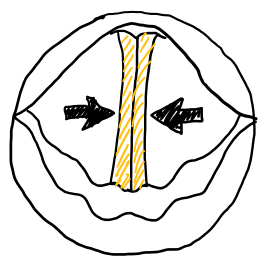

In supraglottic anteroposterior compression, the larynx constricts from the back towards the front so that the arytenoid cartilages (that hold the back or posterior ends of the vocal folds) appear pulled forward, obscuring some or all of the vocal folds (posterior-antero [PA] constriction). Alternatively, the epiglottis (or its base) which lies at the front of the larynx appears pushed backward, obscuring the front/mid portion of the vocal folds (antero-posterior [AP] constriction) and allowing the cuneiform cartilages to tilt backwards. In the lateral compressions, the vocal folds seems long and stretched, and the false vocal folds walls of the larynx appears to be pulled towards the midline.

Besides the possibility of increased tension in cricothyroids, suprahyoids, and/or intrinsic adductory muscles, patients with VH may present excessive tension in the infrahyoid muscles, additional strap musculature (e.g., sternocleidomastoid), respiratory muscles, oral (lip/tongue) muscles, and/or abductory intrinsic laryngeal muscles (McKenna et al., 2020).

[tabs]

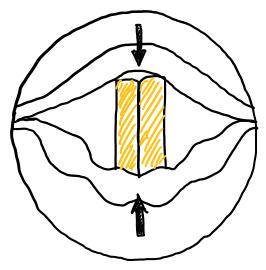

[tab title=”MTD type 1: The laryngeal isometric“]

Generalized tension in all the laryngeal muscles is often associated with an open posterior glottic chink due to persistent posterior cricoarytenoid muscle pull during phonation. This leads to secondary mucosal vocal fold changes including nodules and chronic laryngitis of polypoidal degeneration.

The laryngeal isometric is frequently associated with palpable increases in suprahyoid muscle tension on phonation, particularly in higher pitch ranges during singing and during high vowels and phoneme transitions in connected speech.

[/tab]

[tab title=”MTD type 2: Lateral Contraction and/or hyperadduction“]

Simple vocal misues with hyperadduction of the vocal folds produce a tense-sounding voice due to incorrect vocal technique. Phonation is probably associated with high laryngeal resistance forces, so patients may complain of “vocal fatigue” and discomfort at the end of a working day. There may be surges of uncontrolled expiratory air, and an effortful and harsh voice with rapid fatigue results from this. With ongoing compression, the voice pitch may drop, and vocal fry register may become prominent, suggesting that there may be associated AP constriction. The fatiguing voice may also be accompanied by general fatigue as well as discomfort or pain in the throat.

[/tab]

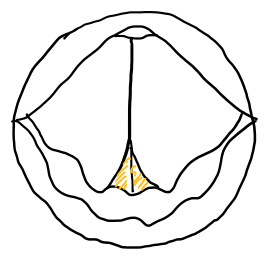

[tab title=”MTD type 3 – Anteroposterior contraction of the supraglottic larynx“]

Koufma has presented a voice type labeled “BogartBacall” syndrome in which patients exhibit a tension-fatigue dysphonia with phonation at the very bottom of their vocal dynamic ranges. “BogartBacall” syndrome is characterized by a contraction pattern which results in reduced space between the epiglottis and the arytenoid prominances in the anteroposterior (AP) direction during phonation. According to Koufma’s findings, individuals using this posture complain of effortful voice and rapid fatigue when speaking at a low pitch but are able to talk more clearly and freely at a higher pitch. However, this laryngoscopic pattern is not readily seen with mirror examination or with the rigid telescope because the tongue pull may extend the aryepiglottic length. Transnasal examination during connected speech or song is the most effective way to demonstrate this misuse, which may then be subclassified as mild, moderate or severe.

[/tab]

[tab title=”MTD type 4 – Conversion aphonia“]

The anxiety that leads to conversion hysteria has produced such mental pain that a physical symptom such as aphonia is much more bearable to the individual. The type of psychological stressors and the resulting muscle misuse pattern differs from anxiety related tension misuses associated with type 2a described above. In conversion disorder, the misuse may be beyond the awareness of the patient, hence the typical “la belle indifference” facial features. The vocal folds have full movement and can adduct normally for cough or other types of vegetative phonation such as laughter. But they stop short of sufficient adduction for voicing with an attempt to speak. Generalized hypertonicity can be identified in the larynx and, when sound does come out, it is usually high pitched, squeaky, or breathy.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

[/toggle]

[accordion]

[toggle title=”If you are interested in watching the inside larynx of MTD, please click here!”]

[/toggle]

These methods may release your MTD symptoms!

People without voice disorders may also occur voice muscle tension symptoms, and longtime inappropriate voice usage will lead to vocal lesions. Especially for professional voice users, the high vocally demanding with increased risk for vocal disability. The MTD needs to be treated effectively because it can affect their professional activity and even their quality of life.

Various treatment has been used for MTD. The two effective directions of the treatments are indirect and direct methods. Indirect methods include vocal hygiene and voice conservation education, and direct methods use vocal exercises, facilitating vocal techniques, and circumlaryngeal massage to increase the efficiency of voice production and reduction of extra laryngeal muscle tension(Craig et al., 2015).

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Circumlaryngeal massage”]

The palpatory evaluation can help to find the excessively tension muscles. Manual repositioning of the larynx or improving the breathing support to consequently reduce the muscle tension. You can use the pads of the index, second, and third fingers of both hands to test the sternocleidomastoid muscles at the start and then the supra laryngreal area. Clinical experience suggests that massage of these muscles lateral to the larynx reduces this tension, thereby reducing the patient’s discomfort and consequently their distress and anxiety, at an early stage of the intervention. Subsequent kneading, and consequent softening, of the supralaryngeal area allows the high-held larynx to lower (Mathieson et al., 2009).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Breathing exercise”]

The breathing exercises included the following steps (Hoit, 1995):

- “observation of abdominal protrusion and retraction on inhalation and expiration in a vertical position,

- participant standing against a wall so that the buttocks and shoulders made some wall contact to improve the body posture, particularly the head position,

- practicing abdominal breathing at rest while sitting, standing, and walking,

- training the participant to sense the abdomen and rib cage getting larger on inhalation and getting smaller and tightened on exhalation via placing one hand on the central abdomen and the other hand laterally low on the rib cage,

- adding phonation activities when participant could contract the abdominal muscles on expiration,

- requesting the participant to prolong vowel joined with continuant consonants with and without abdominal support and compare the differences between them,

- using perceptual cues: improve the concept of increasing air volume via increasing chest expansion. Explain that more air volume for expiration–phonation leads to singing more words per breath without strain.”

[/toggle]

If you have a voice problem that persists beyond several weeks and is not because of a routine cold or flu, please go to see the otolaryngologist for a specialty laryngeal exam and get an accurate diagnosis. There is never a bad time to see a voice specialist to ensure alonger vocal career.

This information is intended for guidance purposes only and is in no way intended to replace professional clinical advice by a qualified practitioner.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”References”]

Angelillo, M., Maio, G. D., Costa, G., Angelillo, N., & Barillari, U. (2009). Prevalence of occupational voice disorders in teachers. 7.

Baker, J., Ben-Tovim, D. I., Butcher, A., Esterman, A., & McLaughlin, K. (2007). Development of a modified diagnostic classification system for voice disorders with inter-rater reliability study. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 32(3), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14015430701431192

Craig, J., Tomlinson, C., Stevens, K., Kotagal, K., Fornadley, J., Jacobson, B., Garrett, C. G., & Francis, D. O. (2015). Combining voice therapy and physical therapy: A novel approach to treating muscle tension dysphonia. Journal of Communication Disorders, 58, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2015.05.001

Fernández, S., Garaycochea, O., Martinez-Arellano, A., & Alcalde, J. (2020). Does more compression mean more pressure? A new classification for muscle tension dysphonia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(7), 2177–2184. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00042

Garaycochea, O., Navarrete, J. M. A., del Río, B., & Fernández, S. (2019). Muscle tension dysphonia: Which laryngoscopic features can we rely on for diagnosis? Journal of Voice, 33(5), 812.e15-812.e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.04.015

Hoit, J. D. (1995). Influence of body position on breathing and its implications for the evaluation and treatment of speech and voice disorders. Journal of Voice, 9(4), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0892-1997(05)80196-1

Mathieson, L., Hirani, S. P., Epstein, R., Baken, R. J., Wood, G., & Rubin, J. S. (2009). Laryngeal manual therapy: A preliminary study to examine its treatment effects in the management of muscle tension dysphonia. Journal of Voice, 23(3), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.10.002

McKenna, V. S., Hylkema, J. A., Tardif, M. C., & Stepp, C. E. (2020). Voice onset time in individuals with hyperfunctional voice disorders: Evidence for disordered vocal motor control. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(2), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00135

Norton, N. S., & Netter, F. H. (2012). Netter’s head and neck anatomy for dentistry (2nd ed). Elsevier/Saunders.

Payten, C. L., Chiapello, G., Weir, K. A., & Madill, C. J. (2022). Frameworks, terminology and definitions used for the classification of voice disorders: A scoping review. Journal of Voice, S089219972200039X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.02.009

Ramig, L. O., & Verdolini, K. (1998). Treatment efficacy: voice disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41(1). https://doi.org/10.1044/jslhr.4101.s101

Roy, N., Merrill, R. M., Thibeault, S., Gray, S. D., & Smith, E. M. (2004). Voice disorders in teachers and the general population: Effects on work performance, attendance, and future career choices. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47(3), 542–551. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2004/042)

Sundberg, J. (1977). The acoustics of the singing voice. Scientific American, 236(3), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0377-82

Sundberg, J. (1989). The science of the singing voice. Cornell University Press.

Van Houtte, E., Van Lierde, K., & Claeys, S. (2011). Pathophysiology and treatment of muscle tension dysphonia: A review of the current knowledge. Journal of Voice, 25(2), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.10.009

Van Houtte, E., Van Lierde, K., D’Haeseleer, E., & Claeys, S. (2010). The prevalence of laryngeal pathology in a treatment-seeking population with dysphonia: Prevalence of laryngeal pathology. The Laryngoscope, 120(2), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.20696

[/toggle]

Leave a Reply