Tomorrow is the big day: my graduation recital. I will get to play all these beautiful pieces I’ve been practicing so hard for the past year… What a joy to share music with the people I love!… Actually… I can’t wait to be done with this burden… I will finally be free…! Hold on. I feel butterflies in my stomach. I think I will be sick… What if I cancel?!… No way… I love the pieces!… I have prepared for it. Wait… The entire school should be there… The other students from my studio will probably judge me. Oh no, I don’t feel hungry at all!… I think I am skipping dinner…

(The day after…)

Ok… I am about to enter stage… Lights are off. The concert hall suddenly feels so cold… My hands are sweating! My heart is suddenly beating so strong! Wait… my mouth is so dry. I feel like I have a stone in my stomach… My energy level is so high... I am breathing too fast! Deep inhale. Exhale. Focus. It’s time. I got this!

STOP –

Let’s freeze in that story for a moment.

As a musician, have you ever felt similarly before a performance?

I am guessing you probably have…

Also, you probably might have already experienced a Flow state when performing.

Hold on… Flow?!?! Don’t you mean Music Performance Anxiety???

Well… I actually would like to discuss both. Music Performance Anxiety (MPA), sometimes called stage fright, is an exaggerated and incapacitating fear of performing in public.

It afflicts individuals who are generally prone to anxiety, particularly in situations of high public exposure and competitive scrutiny, and so is best understood as a form of social phobia (a fear of humiliation).” (Wilson & Roland, 2002)

But you probably already know a lot about music performance anxiety (MPA), as this is a very common problem among musicians… Because of that, I’d like to introduce you to the concept of flow on this blog post, which has been found to help transform MPA into a more positive energy.

[toggle title=”WHAT IS FLOW?“]Flow is, at the same time, a relaxed but intensely focused state that has received attention as being among the indicators of an individual’s well-being. Often described by sport athletes as “being in the zone”, there are three common elements usually present in the flow state: absorption (‘‘the total immersion in an activity’’), enjoyment, and intrinsic motivation.

In order to experience flow during a performance, one needs to be deeply and actively involved in the task, with a high level of concentration and performing at the peak of their ability, which indicates a state of heightened arousal (De Manzano et al., 2010).

[/toggle]

Now, let me give you some good news:

Flow experiences are also very common among music performers. A previous study has shown that 95% of elite music students and 87% of amateur students reported experiencing flow frequently (Sinnamon et al., 2012).

According to several studies, flow can also be perceived as positive stress (eustress), which is usually the result of more manageable levels of stress.

“Hold on… positive stress??? Isn’t stress bad???”

Well… stress can be both very detrimental and beneficial! Stress by itself is not bad, but anxiety, chronic stress and not returning to a resting state (homeostasis) can be really detrimental to our health and general sense of well-being. In music specifically, stress can harm our performance abilities. But I am sure you probably know a lot about the detrimental aspects of distress.

Now, let’s keep focusing on the good news.

“Now you are being very optimistic… is there anything positive about being stressed out?!?!”

Well, if you are trying to achieve an optimal performance state, yes, there is!!!

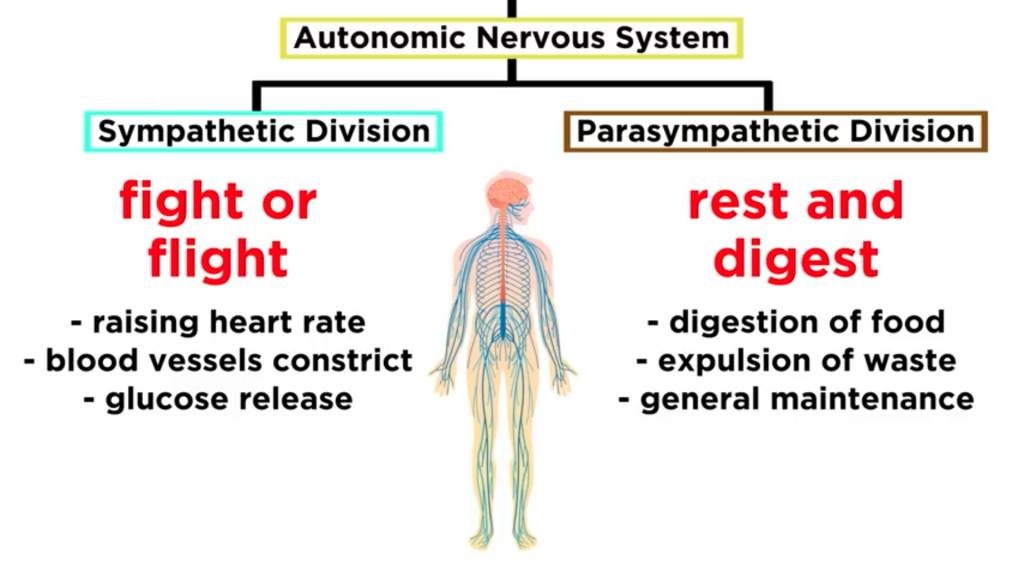

[toggle title=”BUT… IS FLOW A RELAXED STATE?“]According to previous studies, the experience of flow is associated to an increased level of arousal through a co-activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system (de Manzano et al., 2010; Harmat et al., 2015). Therefore, an increased arousal on both parasympathetic and sympathetic systems results in simultaneous relaxation and readiness for action. Flow is therefore described as a state of:

Therefore, an increased arousal on both parasympathetic and sympathetic systems results in simultaneous relaxation and readiness for action. Flow is therefore described as a state of:

effortless attention that can be experienced during task performance as a result of an interaction between emotional and attentional systems” (Ullén et al., 2010).

This helps us understand why increased arousal is beneficial and even necessary to music performance.

[/toggle]

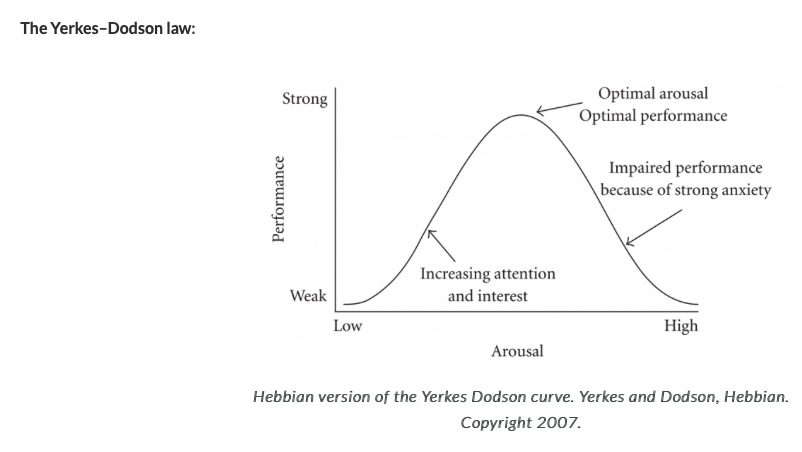

[toggle title=”HOW DOES AROUSAL DURING MPA AND FLOW DIFFER?“]That’s a good question. Research suggests that moderate physiological arousal should facilitate flow-experience, but excessive physiological arousal hinders flow and often causes MPA. The relation between arousal and level of performance follows an inverted U-curve as shown below:

Now, let’s go back to the initial story for a moment. Below are some of the symptoms mentioned by the narrator and the physiological explanation of why we often feel this way before a performance.

| Butterflies in the stomach; “don’t feel hungry” | Diversion of resources away from digestion in order to be ready to an emergency situation |

| Cold and sweaty hands | Activation of the body’s cooling system |

| Dry mouth | Redirection of body fluids such as saliva into the bloodstream |

| “Heart beating so fast” | Increased heart pumping |

Although often associated to MPA, these symptoms may also relate to a flow state, when the level of focus and concentration is high. Being aware of this may help musicians understand what is going on in their bodies when they are about to perform and demonstrate that these body reactions should not necessarily be perceived as negative and distressful.

We can say flow and performance anxiety are antithetical states, which means that they are negatively related (Fullagar et al, 2013). The two can exist simultaneously but the presence of one minimizes the potential of the other.[/toggle]

[toggle title=”HOW DO WE DESCRIBE FLOW???“]Studies in Flow generally use nine specific dimensions to describe this state in performers, which are:

1. Balance between perceived challenge and skill to overcome it.

2. Action-awareness merging (doing things spontaneously and automatically without having to think).

3. Clear goals (a strong sense of what to do).

4. Unambiguous feedback (a good perception of how well one is doing during the performance itself).

5. High concentration (being completely focused on the task).

6. Sense of control (having a feeling of total control over the performance).

7. Loss of self-consciousness (not worrying about what others may think if oneself).

8. Transformation of time (a sense that time passes in a way that is different from normal).

9. Autotelic experience (feeling the experience to be extremely rewarding).

(Sinnamon et al., 2012)

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”FLOW AND PHYSIOLOGY“]Previous studies demonstrated that Flow has physiological effects on the performer and suggested that Electromyography (EMG), cardiovascular, and respiratory measures are all significantly associated with the flow experience.

De Manzano et al.,(2010) suggested that:

During a physically and cognitively demanding task, an increased activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system in combination with deep breathing and activation of the zygomaticus muscle might potentially be used as an indicator of effortless attention and flow.” (De Manzano et al., 2010, p. 306)

“It is interesting to note that a concomitant increase in parasympathetic tone to counter sympathetic activation has also been found to occur during attention demanding meditative states that are characterized by a combination of restfulness and heightened concentration”. (De Manzano et al., 2010, p. 306)

[/toggle]

HOW CAN I MANAGE MY STRESS TO AN OPTIMAL LEVEL IN ORDER TO FACILITATE FLOW?

I don’t think there is a magic formula for that (at least not yet!) but right now you are already on the right track and asking yourself the right question. Have you heard about Positive Psychology in music? (Yes… I still want to give you more positive insights in this blog post!)

The positive psychology movement led by Dr. Seligman (2011) suggests that health is not only the absence of pathology or disease, but rather the presence of well-being. In this way, he suggests that methods to facilitate positive functioning need to be actively cultivated. Based on that, our target as musicians shouldn’t be restricted to finding solutions to reduce MPA, rather we should focus on both facilitating flow as well as reducing MPA. This approach could be very beneficial and effective to achieve an optimal performance level.

If such an intervention became a normative part of the music education process, musicians would be able to acquire the necessary performing skills to enable them to produce optimal performances, without suffering from stigmatized, debilitating MPA or needing to resort to pharmacological help.” (De Manzano Et al., 2012)

Ok, now that we have adopted a more positive approach, let’s go back to the initial question:

Many approaches exist and need to be chosen according to each individual’s needs.

Here are two strategies that should help musicians reach flow and provide support to educators who seek to foster optimal performance experiences with their students.

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

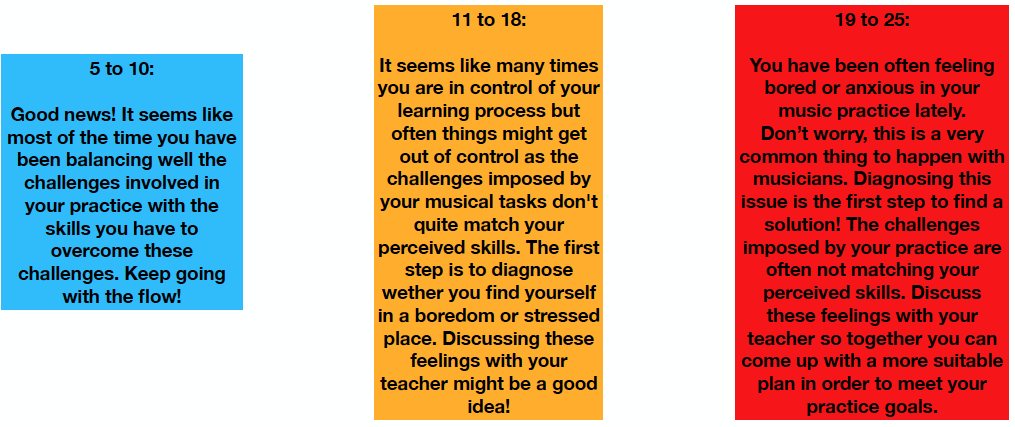

[toggle title=”CHALLENGE/SKILL BALANCE“]Among the nine dimensions that can induce the flow state, challenge/skill balance is the most dominant one and has a central role in understanding optimal performance.

There are basically two components of this dimension that must be met to achieve a flow state:

1. The perceived challenges required to complete the task must match the perceived skills of the performer (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002);

2. Challenges and skills should be at a moderate to high level, so that the activity is challenging but at the same time doesn’t overcome the skills.

For example, if a music student is working on a piece that is too easy for their skills, they might get bored. On the other hand, if the repertoire is too challenging and overmatch the existing skills of the performer, they might easily enter the anxiety state. Check the following section for a challenge/skill balance quick check up![/toggle]

[toggle title=”QUICK SELF CHECK UP:”]Let’s do a quick challenge/skill balance check up. Grab a piece of paper and write down your answers from 1 to 5: How often do you feel this way?

“I feel too anxious and stressed when working on this repertoire. I don’t feel motivated to practice.”

1.Never 2.Rarely 3.Sometimes 4.Quite often 5.Always

“It feels like time passes so slowly when I am practicing. The repertoire I am playing seems boring and I often get trapped by other distractions such as my phone.”

1.Never 2.Rarely 3.Sometimes 4.Quite often 5.Always

“I am not sure exactly how to work on the technical aspects of this piece in order to perform it well.”

1.Never 2.Rarely 3.Sometimes 4.Quite often 5.Always

“I don’t have a clear plan for my practice this week.”

1.Never 2.Rarely 3.Sometimes 4.Quite often 5.Always

“I have already overcome most of the challenges of this repertoire. It feels too easy and not engaging at

this point.”

1.Never 2.Rarely 3.Sometimes 4.Quite often 5.Always

Now take some time to sum up all the points for your answers.

Depending on your total amount, here are some tips for you:

[toggle title=”SETTING CLEAR PRACTICE GOALS“]This is very simple to understand: in order to perform, we need to practice and in order to achieve an optimal performance, we also need to prepare ourselves with an optimal practice session.

Many studies show that goal setting encourages the development of flow. Also, there is evidence that the parameter of setting clear goals is higher in sport athletes than in musicians when the two groups are compared. This is an expected result, since it is easier to set goals in sport where there is a better sense of control of the achievement, than in music, which is an artistic discipline and subject to individual interpretations (Habe et al, 2019).

Setting clear goals is a key element to build an optimal practice environment when one feels an intense concentration and clear internal feedback (Araújo, 2019). Therefore, musicians should create optimal goals for each practice section, which are clear, proximal, achievable and challenging. In the same way, teachers should also work on this with their student in order to help them setting practice goals.

When experiencing flow during practice, there is often a feeling that the session was a rewarding one and that the time has passed differently from the norm. (Araújo, 2019).

[/toggle]

To conclude…

Striving for an optimal practice is the first step to achieve an optimal performance. So… don’t wait any longer! Before you start your practice session today, grab a piece of paper and ask yourself the following questions:

- What are my practice goals for this session? Take some time to define and write down clear, challenging, achievable and proximal goals.

- Am I giving myself enough feedback about my own performances?

- If not, recording your practice session or listening to your performances and writing down a few points you need to improve at might be a good way to give yourself some helpful feedback.

- Am I in control of my learning process?

- If you feel you are not, take some time to reflect on what exactly you are trying to learn and define the specific and technical processes to help you reach your goals. Remember you should always strive to be your own best teacher and coach!

Ok, this was probably a lot of information to digest in one sitting… So please remember:

- If you feel some of the “scary symptoms” mentioned in this post before your next performance, don’t panic! Remind yourself that this is a normal reaction happening in your body. An increased arousal state can help you to “be in the zone” and achieve your optimal performance state.

- Strive to build an optimal practice routine. Optimal practices lead to optimal performances. Find a balance between the challenges in your tasks and the skills you have to solve them and set clear goals to your practice sessions.

- Try to keep a positive attitude. Above all the stress involved in being a musician, we still have the luxury of doing what we love and experiencing flow so often.

I hope these “Flow tips” will help you on the fascinating journey of performing and teaching music!

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

Take care and… go with the flow!

Author: Julia Laporte Bomfim

[toggle title=”References:“]

Araújo, M. V., & Hein, C. F. (2019). A survey to investigate advanced musicians’ flow disposition in individual music practice. International Journal of Music Education, 37(1), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761418814563

Bakker, A. B. (2005). Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 1 (66), 26-44.

Cohen, S., & Bodner, E. (2019). The relationship between flow and music performance anxiety amongst professional classical orchestral musicians. Psychology of Music, 47(3), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735618754689

Cohen, S., & Bodner, E. (2021). Flow and music performance anxiety: The influence of contextual and background variables. Musicae Scientiae, 25(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864919838600

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience (First Harper Perennial Modern Classics, Ser. Harper perennial modern classics). Harper Perennial.

Fulllagar, C. J., Knight, P. A., & Sovern, H. S. (2013). Challenge/skill balance, flow, and performance anxiety. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 62(2), 236-259

Habe, K., Biasutti, M. & Kajtna, T. (2019). Flow and satisfaction with life in elite musicians and top athletes. Frontiers in Psychology. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00698

Horwitz, E., Harmat, L., Osika, W. & Theorell, T. (2021). The interplay between chamber musicians during two public performances of the same piece: a novel methodology using the concept of flow. Frontiers in Psychology. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.618227

Manzano, O., Harmat, L., Theorell, T., & Ullen, F. (2010). The psychophysiology of flow during piano playing. Emotion, 10, 301-311

Parncutt, R., & McPherson, G. (2002). The science & psychology of music performance:

creative strategies for teaching and learning. Chapter 4: Performance Anxiety. Oxford University Press.

Sinnamon, S., Moran, A., & O’Connell, M. (2012). Flow among musicians: Measuring peak experiences of student performers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 60, 6-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022429411434931

Wrigley, W. J., & Emmerson, S. B. (2011). The experience of the flow state in live music performance. Psychology of Music, 41, 292-305. doi: 10.1177/0305735611425903.

[/toggle]

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”Credits for images:“]

1. “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder” by Truthout.org is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

2. “jean nouvel, danish radio concert hall, 2002-2009” by seier+seier is licensed under CC BY 2.0

3. “Jump Sky High (free CC usage with credit link to LiveWildPhotos.com)” by liveoncelivewild is licensed under CC BY 2.0

4. “stress” by disenoterapia is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

5. Yerkes-Dodson Law curve via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HebbianYerkesDodson.svg

6. “Think Positive” by Wavy1 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

7. “Owharoa Falls, Waikino, Karangahake Gorge” by DΕΠΠΙS is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

[/toggle]

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

Thank you so much for this blog. It will be very useful in teaching and as a reminder of the different things we can do while rehearsing and performing to stay focused and flowing! Thank you!

I think that the information presented in this blog is very useful and clearly laid out. In general, music schools do not offer classes that cover such important topics as the ones found here. Thank you and bravo!

Daniel

Thank you very much, Daniel!

I am glad the information was useful to you!