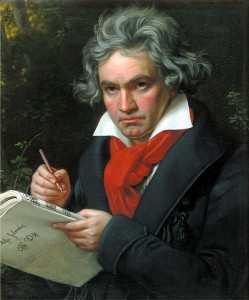

The idea of a musician that is hard of hearing might sound like an oxymoron, but it is more common than one would think. Though deaf for the last eight years of his life, composer Ludwig van Beethoven continued to compose music until his death. Bedrich Smetana, a Czech composer, was also deaf for the last ten years of his life. Evelyn Glennie, as seen in her Ted Talk, has been profoundly deaf since the age of twelve, yet leads an active career as a professional percussionist. While I have only listed three examples, there are many more professional musicians as well as music lovers who suffer from hearing loss all over the world. Having a hearing impairment does not prevent individuals from participating in musical activities, nor does it prevent them having fruitful careers.

But as society continues to make numerous technological advancements, why have hearing aids for musicians not followed suit?

[toggle title=”References”]Fulford, R., Ginsborg, J., & Goldbart, J. (2011). Learning not to listen: the experiences of musicians with hearing impairments. Music Education Research. 13(4), 447-464. [/toggle]

[toggle title=”For more information”]Deaf musicians shatter myths about hearing impairments and sound. (2015, January).

Seeger, P., Jacobs, P.D., & Christie, R.G. (2006). The deaf musicians. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. [/toggle]

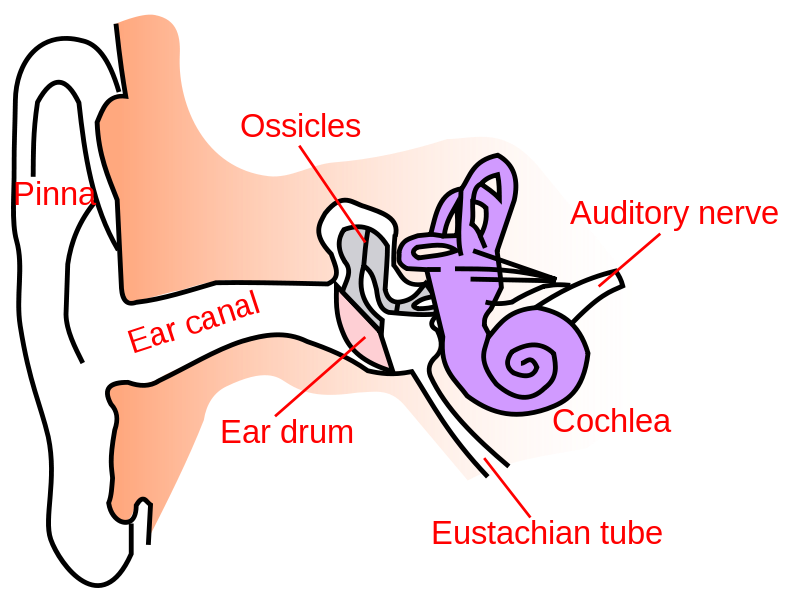

How do we hear?

The ear has three main subsections: the outer ear (which contains the pinna), the middle ear (which contains the ear canal, ear drum, and ear ossicles), and the inner ear (which contains the cochlea and auditory nerve). The middle and inner ear measure to be approximately the size of a penny. The pinna channels sound through the ear canal into the middle ear, where the sound is transformed into mechanical vibrations by means of the ear drum. These vibrations are passed through the ossicles (the three smallest bones in the human body) where they then travel into the cochlea, located directly in the bone of the skull. Here the sound information is transformed into electrical signals and sent to the brain to be processed and interpreted via the auditory nerve.

[toggle title=”References”]

Lloblet, J.R.I., & Odam, G. (2007). The musicians body: A maintenance manual for peak performance. England: The Guildhall School of Music & Drama and Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Tan, S-L., Pfordresher, P., & Harre, R. (2010). Psychology of music: From sound to significance. East Sussex: Psychology Press. [/toggle]

[toggle title=”For more information”] Van Evra, J. (2015, April). How music works: Surprising answers to your questions about sound.

How does the ear work? (2015). [/toggle]

What are hearing aids and who uses them?

Hearing aids are used by individuals with mild to profound hearing loss. In order for the hearing aid to function, those who use them must have some remaining inner ear hair cells in their cochlea. Over the 20th century, hearing aids have evolved from the non-electric ear horn (or ear trumpet) to the development of digital hearing aids at Bell Laboratories in the 1960s (Levitt, 2006). The first hearing aid to become commercially available was worn around the body but after limited commercial success as well as further technological advancements, a digital hearing aid small enough to wear within the ear was developed in the 1990s.

A hearing aid is a small electronic instrument used to amplify sounds to assist people with hearing disorders better hear and communicate with the world around them. As described by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), there are presently many styles of hearing aids including the behind-the-ear (BTE), the mini BTE, the in-the-ear (ITE), the in-the-canal (ITC), and the completely-in-canal (CIC).

A present day hearing aid has three basic parts: a microphone, which converts sound into electrical signals, an amplifier, which increases the volume of the sound, and a speaker, which sends the amplified sound to the brain for processing. Hearing aids are able to convert sound in two different ways: (1) through analog aids, which process electrical signals, and through (2) digital aids, which processes sound using numerical codes and computer processes.

[toggle title=”References”]

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”For more information”] Types of hearing aids. (2014). [/toggle]

What are decibels and how do they affect me?

Most people believe that the loudness of a noise (measured in decibels, dB) is the major contributing factor to hearing loss when it is really the balance between the intensity of the noise and how long you are exposed to it (Witt, 2006). The current acceptable decibel exposure guidelines come from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). They provide national and world leadership to prevent workplace illness or injury. NIOSH suggest that for every 3 dBs over 85 dB, the permissible exposure time to that sound is cut in half. Therefore, the more intense the sound, the shorter the amount a time a person is able to be exposed to it without damage. Exposure to an average sound of 85 dB for 8 hours produces the same risk than an average of 88 dB for 4 hours, or 91 dB for 2 hours. Examples of the decibel levels of common sounds include rustling leaves at 20 dB, whispering at 40 dB, normal conversation at 60 dB, busy city traffic at 80 dB, hair dryers at 90 dB, full volume personal music players at 100 dB, rocker concerts at 110 dB, jet plane take off at 120 dB, and fireworks and gunshots at 140 dB. To view an interactive noise meter, please click here.

[toggle title=”References”]

Chesky, K. (2008). Hearing conservation and music education. Seminars in Hearing, 29(1): 90-93.

Workplace safety & health topics: Noise and hearing loss prevention. (2012).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”For more information”]

[/toggle]

Do hearing aids fit musician’s needs?

As discussed earlier, hearing aids have gone through many technological advances in the 20th century. Unfortunately, as audiologist Dr. Marshall Chasin, a leading figure in the field of music and audiology, has described in his research, the majority of the advancements have unfortunately focused primarily on speech perception as the primary input. Due to this focus on speech perception rather than music, many musicians who use hearing aids notice problems in crispness, fullness, naturalness, and overall fidelity in the music they listen to and produce. The idea of music as an input is a relatively new concept to audiologists.

As discussed by Chasin and Russo (2004), there are three main differences between speech and music including the frequency spectrum, the intensities, and the crest factors, as described below.

The speech spectrum, as characterized by Byrne et al (1994), is fairly uniform. Though male, female, and child voices are different in pitch, they are generated by the same oral and nasal cavities, and therefore tend to be quite predictable and share similar characteristics, even across different languages and dialects. On the other hand, the music spectrum is highly variable due the variety of instruments, and technological innovations which have increased the ranges and capabilities of instruments.

Intensity is the measurement of sound power. The human vocal tract has a limited sound intensity output. Most speech ranges between 50-85 dB (from soft speech to shouting). As speech is in mind for most hearing aids, the peak input limiting level (or the maximum loudness of input) tends to be set around 85 dB. As music can easily reach 105 dB and peak closer to 118 dB in more intense areas, most hearing aids are unable to handle music as an input.

The final major difference between speech and music, according to Chasin and Russo (2004) and Hockley et al. (2004), is the crest factor, or the “the instantaneous difference between the peak signal and the overall level.” Speech has a crest factor of 12 dB and music has a crest factor of 18-20 db.

Now that we understand why hearing aids are not effective for musicians, why hasn’t there been any advancement in the field? Musicians especially have a critical dependence on the ability to hear very fine sounds in music, and yet the only hearing aids available to them continue to negatively affect the overall fidelity of the music. Perhaps the market is not big enough to fund the research needed to improve hearing aids for musicians. I can only hope that audiologists, sound engineers, and professional musicians with hearing aids are able to work together in future to create suitable hearing aids for all types of inputs.

[toggle title=”References”]

Chasin, M. (2003). Music and hearing aids. Music and Hearing, 56(7), 36-41.

Chasin, M., & Russo, F.A. (2004). Hearing aids and music. Trends in Amplification, 8(2), 35-47.

[/toggle]

Musical hearing aids of the future

Presently, hearing aids do not meet the needs of professional musicians who are hard of hearing. There are many parameters that must be researched and experimented on to improve the overall listening experience. According to Chasin (2003), the four main parameters that would aid listeners include changes in the peak input limiting level (the inputs’ volume limit), the use of channels, the knee-point of the input-compression circuit (where the sound rate in which a sound is amplified decreases), and the wide dynamic range compression circuit.

As music is quite dynamic, and highly variable, the peak input-limiting level, or the maximum input level, of hearing aids should be at least 115 dB. The low peak input-limiting levels that are presently in hearing aids cause distortion as hearing aids assume any sound over 85 dB as unimportant, thus limiting the listener. The knee-point of the input-compression circuit, or the level where the compression of sound begins in non-linear amplification, should be set higher for music as the crest factors between speech and music are very different. A wider dynamic range compression circuit allows listeners to hear all frequencies represented in the music, and the use of one channel rather than multiple, balances frequencies and harmonies.

As Chasin describes, “the input spectrum of music is inherently quite variable and significantly different from that of speech. Hearing aids need to be designed with this and the signal dynamics of music in mind from the very onset of development” (Chasin, 2003).

[toggle title=”References”]

Chasin, M. (2003). Music and hearing aids. Music and Hearing, 56(7), 36-41.

[/toggle]

For now, is there a quick fix?

Hearing aids are far from being able to optimally amplify music. More research between audiologists and musicians must be performed in order to make further advancements in this field. Until then, audiologist Dr Marshall Chasin suggests the following adjustments to improve the musical fidelity. The suggestions fall into two major groups, (1) improving the hearing aids capacity to handle louder inputs, and (2) decreasing microphone sensitivity and involve both creative strategies and electro-acoustic techniques.

As discussed in Chasin and Hockley (2014), strategies include turning down the input sound volume and turning up the hearing aid volume, as well as even removing the hearing aid altogether while playing or listening to music. As described in his 2010 article, Chasin has suggested that his clients bring a balloon to a live performance, so that as they hold the balloon to their ear, the vibrations and frequencies bouncing on the balloon allow for a vibro-tactile response. Placing a piece of tape over the microphone lowers the sensitivity and allows more intense music to be lowered by 6-10 decibels, which leads to a higher quality listening experience. If experiencing difficulty hearing the instrument you are playing, think about switching to an instrument in a different register.

Hearing aid technologies may not be optimal as of yet, but there are some that will help with the quality of music heard. Your audiologist can introduce you to new technologies that allow for more intense music to be induced by hearing aids. Your audiologist can also change the dynamic range settings, and suggest different microphones.

[toggle title=”References”]

[toggle title=”Photos sourced from Creative Commons”]

[/toggle]

Great topic! I never thought about how musicians with hearing aids might hear the music differently. Also — I love the idea of using a blog as a class assignment in a seminar course!

Thanks JP! The blog as a final assignment was certainly a refreshing idea. Glad you enjoyed it!

Very interesting read! Thanks for all the pertinent information- especially with all of the future research to be done by audiologists.

It’s easy to see the importance for new research and hearing aid advancements from your blog, Jesse. Well done. I hope that audiologists will combine with musicians to do this. Is the reason for a lack of advancement purely economics? Is market for hearing aids for musicians just too small to get the attention of business and researchers?

Amazing write up, Jesse! A friend of mine does have minor hearing issues in that at times, she cannot hear the 3rd of a chord given from time to time. I wonder if Martha de Francisco, sound recording engineer and professor at McGill, could shed any light on this topic? I wonder even if this device could help in music education in the future? I have taught a handful of students that have trouble matching pitch and maybe a hearing aid device could assist them in hearing the tones more clearly.

Thanks for reading Rolfe! I have worked briefly with Martha de Francisco in a sound recording seminar, but had never thought of contacting her to learn more on the topic. Thanks for the idea!

As I am pursuing my Bachelors of Education (with music being one of my teachables) I believe it’s important to understand that even if a student has a hearing aid, what they hear is different than what I would hear. I hope more research is done on this in future!

Hey Erica! Thanks for the reply. I completely agree! I wish I had known this information before going on practicum in my Bachelor of Ed. But better late than never I guess!

Jesse! What an intriguing blog! I’ve always been curious about the musician who is hard of hearing. That was a great read, and very educational might I add! I particularly enjoyed the topic of the hearing aid and how it’s used. Very well researched and written- awesome job!

Having just purchased new hearing aids, I know all too well how little focus the manufacturing companies seem to have on allowing people who are hard of hearing to experience hobbies as well as just hear speech better. As a musician I do have a special music setting on my hearing aids which is at least an improvement on the regular program, but it’s still not enough. It’s unfortunate, because it is so easy now to provide seniors in homes with the music they love on portable devices, but those who have lost their hearing can’t enjoy it fully. Not to mention other people who are much more active than the stereotypical hearing aid user, particularly children and young adults.

Sadly, I don’t have much hope for the near future. It’s only been recently that waterproof hearing aids have become available at a reasonably affordable price, which when you think of the huge advances we’ve seen in other technologies (i.e. smartphones) over the past decade or two, is ridiculous. Being able to hear while swimming is a huge part of feeling safe in the water, not to mention the constant fear of getting caught in heavy rain depending on where you live.

Hey Ashley! Thanks for the reply. I thought of you as I was researching for this blog. You raise a valid point! With the advances in technology, it’s interesting how little hearing aids have progressed. Even if they developed aids that allowed music to be heard well, you’re right — they would probably be ridiculously expensive and not attainable by the general public. If you’re ever interested in learning more about hearing aids and music as an input, I highly suggest Michael Chasin’s work! He specializes in the area and most of his papers are available online.

Great research Jesse! I watched the Ted Talk with the percussionist (Glennie) and I really like her idea surrounding the definition of hearing. I’ve always considered hearing to involve only the ears, but the idea that music can be obtained by one’s whole body is really interesting. Thanks for the share!

Hey Mom! Thanks for reading! I completely agree! I think Glennie’s definition of hearing is definitely something to think about. If you’re interested, she has a movie called “Touch the Sound: A Sound Journey with Evelyn Glennie” which you may enjoy.

Cool! I never considered how music and speech were perceived differently in hearing aids.

Thank you for the blog! I would like to see more research being done with hearing aids and music as an input in future.

Interesting read! I had never considered that hearing aids were made with speech as their primary source of input. If Beethoven were alive today, I wonder how he would react to the hearing aids we have on the market.

OMG! This is sooo interesting! I never considered the fact that hearing aids would be created with only the input of speech in mind. I totally hope further research is done to better hearing aids for professional musicians

Great work, Jesse. I really enjoyed this.