♥Learning Self Love for our Playing♥ Suzanne-Valadon – The Violin Case, Wikimedia Commons

Suzanne-Valadon – The Violin Case, Wikimedia Commons

“I am larger, better than I thought, I did not know I held so much goodness” -Walt Whitman, “Song of the Open Road” (Hanson, & Mendius, 2009)

How do we learn to love our own playing?

Well… before we can learn to love our playing, we must love and be at peace with ourselves.

Have you….

- Ever felt unfocused, unsettled, or scatterbrained?

- Felt lost in your practice session?

- Felt discouraged about your progress, or negative about a recent performance?

- Obsessed over comparison of yourself to others? “She’s more talented than me…”

- Been overwhelmed by stress?

If you have these thoughts, you’re not alone.

Everyone struggles with the same obstacles when it comes to being a musician. Focused, effective, and efficient practice is one of those lifelong mysteries! Learning how to assess yourself critically, yet maintain positive self talk is also one of the hardest things to do. We can only grow as people when we have a healthy mindset, find more self-satisfaction with our playing, and discover what techniques work for us as unique individuals.

It is crucial to encourage healthy physical as well as psychological habits as we embark on this complex journey as musicians. Being a musician requires a tremendous amount of self reflection, and the skills to assess yourself in an honest way, using critical thinking (analyzing strengths and weaknesses) and not pessimistic thinking. It is a spiralling trap that many of us fall into- to obsess over our weaknesses and doubts- and not be able to see our own beautiful strengths and virtues. It is the little victories that are important in growth!

Recently, these types of questions have been on my mind a LOT. So, I decided to start researching and discussing with others methods that could help me with focus, practice, creativity and positivity in this journey as a musician.

And… I came to the following question: Do techniques such as meditation, mindfulness, and yoga help in creating a positive mindset in musicians?

In this blog post, I will share with you a brief overview of a few studies done using these techniques, in the hopes of opening up a discussion or provoking a thought. Of course every individual is different, and a different practice, combination of practices, or no practice at all might be the best for someone in a given situation.

There are many different forms of meditative practices across cultures. Some forms are movement-based (ex. Yoga), while others are contemplative/still (ex. Mindfulness Meditation, Mantra Meditation). These practices have been proven methods to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression in musicians (Van, Hobkirk, Sheppard, Aviles-Andrews, & Earleywine, 2014).

STRESS & ITS EFFECTS:

Stress can be a huge barrier when it comes to working on a positive and focused mindset. Stress is a natural, biological reaction to our surroundings. It works to our advantage to a certain extent, but when we become overstressed it can overwhelm and inhibit us. Musicians are found to be more prone to stress and rumination than non-musicians (Roy, Radzevick, & Getz, 2016).

The video “How stress affects your brain- Madhumita Murgia” synthesizes a lot of the information below!

However, if you are interested in knowing more details on stress, see below:

[tabs]

[tab title=”What is Stress?”]

Stress is a biological response, which comes from the brain as a result of any stimuli- real or perceived/imagined. Stress response can be generated by a physiological, psychological, or emotional stimuli, and can be internal or external sources. Once stress is triggered, it alters the body’s stability and state of equilibrium maintained by physiological processes (homeostasis) by forcing the body to use a number of adaptive responses in order to carry on (Barbeau, 2017).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Stress Response”]

The nervous system reacts to stress in two phases:

1. Recognizing the situation & 2. Producing the physiological changes appropriate

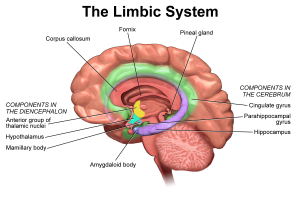

- Limbic system

- Recognizes the situation & identifies it as a potential threat/dangerous

- The limbic system is a network in the

Limbic System, Wikimedia Commons forebrain, which connects to the hippocampus & amygdala

- The hippocampus holds declarative memory (facts, events, places, etc.)

- The amygdala holds emotional memory (particularly negative emotions, ex. fear)

- Both types of memory are linked to our interpretation of future situations

- We often worry about forthcoming events because of past experiences (our memories)

- Hippocampus & Autonomic Nervous System

- Controls the physical manifestation of stress

- The hippocampus is the major centre in the brain which controls metabolic processes (through nerves and hormones) so that the levels are appropriate for the situation at hand (maintains homeostasis)

- It controls the autonomic nervous system and pituitary glands

- The autonomic nervous system is divided in two branches: the sympathetic system and parasympathetic system. The sympathetic system has a stimulatory effect (ex.

HPA Axis. Wikimedia Commons Heart rate, blood pressure, saliva, digestion, pupillary response, respiratory rate), and prepares the body for action- while the parasympathetic system returns body functions to normal.

- Under stress, the hypothalamus (blue area) → signals pituitary gland (green area) → activates adrenal glands (red areas) → releases steroid hormone cortisol. Cortisol allows the body to mobilize energy reserves, and may also suppress the immune system(Barbeau, 2017) (Kenny, 2011).

- The autonomic nervous system is divided in two branches: the sympathetic system and parasympathetic system. The sympathetic system has a stimulatory effect (ex.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Types of Stress”]

Distress is a “bad stress”- a feeling of unpleasant, negative emotion… while Eustress is a “good stress”- a feeling of excitement, anticipation, and passion (Kenny, 2011).

Stress can be Acute – situational, short term response to isolated events, also described as “state anxiety”… or Chronic – prolonged and continuous symptoms, often a character trait of general anxiety, & can cause serious consequences on long term general health (Kenny, 2011).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Fight-or-flight”]

A lot of research, and a lot of what you may know about stress fixates on the fight-or-flight response (which is real!), but more recent research has shown people often respond with highly unique emotional, physiological, cognitive, and behavioural responses to specific stress conditions (Kenny, 2011)!

[/tab]

[tab title=”Physiological, Cognitive, Emotional, & Behavioural Responses”]

There is a wide variety of responses to stress that can occur, depending on the individual, circumstance, situation, etc. Here are some possible impacts of stress:

|

Physiological

|

Cognitive

|

Emotional

|

Behavioural

|

[/tab]

[tab title=”Stress & Rumination in Musicians”]

Rumination is when a person cannot stop thinking about an incident or situation. Normally it is considered a maladaptive thought style characterized by intense, repetitive self-reflection. It is often linked to depression or other negative outcomes.

There was a study done which found that musicians tend to be more prone to negative thought patterns, depression, and rumination than non-musicians. Participants with more musical experience reported experiencing higher levels of stress and lower levels of optimism. It also found a mutual relationship between rumination and depression, and since musicians have a greater propensity for rumination (rumination is often linked closely with artistic creativity and increased perseverance), this may explain the higher incidence of depression in musicians (Roy, Radzevick, & Getz, 2016).

To know more about this topic, see the blog “The many moods of a musician”.

[/tab]

[/tabs]

~ THE BENEFITS OF A STILL MIND ~

The present moment is all we ever have. When we live in the past or anticipate the future, this may create emotions such as regret or worry. As a result, living outside the present can be a great source of anxiety (Noonan, 2014).

There are countless studies that prove the positive effects of meditation and mindfulness. The studies in particular which I will mention here research how separately or in combination: yoga, meditation, and mindfulness can alleviate or decrease factors such as stress, anxiety, music performance anxiety, and confusion… while improving things like flow, mindful awareness, and focus during practice or performance. Obtaining a more mindful disposition when approaching our instrument to practice or perform, whatever it may be, will bring more acceptance, comfort, and confidence.

There are MANY different types of meditation & therapeutic disciplines which all differ from each other but have overlapping aspects. In this blog I will give a brief overview of mindfulness, meditation and yoga. However, it is important to note there are many variations and forms of these practices (ex. Mindfulness Meditation, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction, Zen, Mantra Meditation, Transcendental Meditation, Yoga, etc.)

Below are brief explanations of Mindfulness, Meditation, and Yoga.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Mindfulness”]

Mindfulness has been defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally”. In yoga, mindfulness is often referred to as awareness. Awareness of the present moment requires tuning out thoughts about the past and future. However, mindfulness does not exclude remembering and planning from the human experience. It aims to free attention from remembering and planning in order to focus on the present moment (Butzer, Ahmed, & Khalsa, 2016).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Meditation”]

Meditation in general is not straightforward- it is difficult to classify.

Meditation is “living in the present moment” (Austin, 2015).

Meditation is “a family of techniques which have in common a conscious attempt to focus attention in a non-analytical way, and an attempt to not dwell on discursive, ruminating thought” (Austin, 2015). It aims for freedom from thought pollution. When we are able to relieve ourselves from the incessant chatter, what remains are those few mental processes essential to the present moment.

Sitting quietly for 20 minutes once or twice a day helps most people relax. This helps you get back in touch with the connections between your body and brain.

Meditation usually involves using a simple concentration devise- focusing on breathing, or repeating some simple word which is in keeping with your belief system.

Contrary to cognitive-behavioural treatment, a common practice of psychotherapy, the goal of meditation is not to ‘challenge’ or ‘change’ dysfunctional thoughts and undesired feelings (ex. ‘I am going to fail on stage’), but rather to observe their rise and fall with an open attitude. The literature describes this approach sometimes as ‘acceptance’. Acceptance in meditation practice does not mean giving up or resigning. By fully being aware and accepting what each present moment offers without reacting habitually, one may learn to respond to situations more reflectively (Lin, P., Chang, J., Zemon, V., & Midlarsky, E., 2008).

Meditation then becomes several other things than a way to relax, physically and mentally. It becomes a way of not thinking, clearly, and then of carrying this clear awareness into everyday living. If meditation has already clarified the brain and made it more receptive, personal growth is then more likely to occur (Austin, 2015).

For more information on meditation, see the blog “OMMMm. Meditation? Why…How?“.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Yoga”]

Yoga‘s aim is to integrate the body, mind and spirit. This allows a person to be in harmony with themselves and their environment.

Exercise, breathing, and meditation form the three main yoga structures. Yoga postures and breathing exercises are said to produce great changes in the body as well as influence emotions (Panesar, & Valachova 2011).

[/tab]

[/tabs]

Below is some information on the effects of mindfulness, meditation and yoga.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Yoga, Meditation, and Mindfulness in Musicians”]

There were two studies done with summer fellows at the Tanglewood Institute which explored the benefits of yoga, meditation, and mindfulness in musicians’ lives.

The first study was designed to evaluate the benefits of yoga and meditation for musicians. A total of 45 young adult professional musicians volunteered to participate in a 2 month program of yoga and meditation. They were randomized into a yoga lifestyle intervention group (15 people), a group practicing yoga and meditation only (15 people), or a no-practice control group (15 people). All of the participants in the study completed baseline and end-program self-report questionnaires that evaluated music performance anxiety, mood, playing related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMDs), perceived stress, and sleep quality. Many participants later completed a 1-year follow up assessment using the same questionnaires. Both yoga groups showed a trend towards less music performance anxiety (MPA) and significantly less general anxiety/tension, depression, and anger at end-program relative to the control group, but showed no changes in PRMD’s, stress, or sleep. It also showed that meditation enhanced cognitive and physical performance (Khalsa, Shorter, Cope, Wyshak, & Sklar, 2009).

The second study examined the role of yoga in facilitating positive psychological states, namely psychological flow and mindfulness, particularly during music performance. The study took place over a period of three years -in 2005, 2006, and 2007. Over all three years, there was a total of 60 fellows in a yoga group and 43 fellows in a control condition. Both men and women participated in the study, and they were mostly in their low to mid 20s. The results were measured using a baseline and end-program questionnaire which evaluated dispositional flow, mindfulness, confusion, and music performance anxiety. Compared to the control group, the yoga participants reported significant decreases in confusion and music performance anxiety, and increases in dispositional flow, as well as mindful awareness (Butzer, Ahmed, & Khalsa, 2016).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Mindfulness Meditation Training”]

This study aimed to compare aspects of mindfulness, self-compassion, and emotion regulation, and find which was most predictive of changes in anxiety, depression, and stress. The study included 58 participants who were community individuals experiencing peri-clinical levels (levels just below, at, or above a clinically relevant threshold) of anxiety, depression, and/or stress. The participants were randomly assigned to a mindfulness meditation training group or to a control group. Anxiety, depression, perceived stress, mindfulness, self-compassion, and emotion regulation were all measured using self-report measures. This study concluded that Mindfulness Meditation Training (MMT) showed evidence of meaningful reductions in anxiety, depression, and stress. Since mindfulness is so difficult to self-report and measure, further research in this area is needed. The findings from this study suggested that at its core, self-kindness, self-compassion and emotional balance are critical to the benefits of MMT in anxiety, depression, and stress. It also suggests that mindfulness, as a process, may be more complicated than some have given credit and that attention and emotional balance may be particularly important aspects related to its effects.(Van, Hobkirk, Sheppard, Aviles-Andrews, & Earleywine, 2014).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Mantra Meditation”]

Mantra Meditation has shown to result in the following:

- Reduction in tension/anxiety

- Improvement in stress-related illnesses

- Increased productivity

- Improvement in cognitive functioning

- Lessening of self-blame

- Mood elevation

- Increase in available affect (emotion)

- Increased sense of identity

- Lowered irritability

(Lehrer, Woolfolk, & Sime, 2007).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Impacts of Meditation on the Brain”]

Literature has shown that cultivating mindfulness might be associated with changes in the brain’s physical structure. A study done by Lazar et. al (2005) used magnetic resonance imaging to assess cortical thickness in long-term mindfulness meditation practitioners. Their results showed that brain regions associated with attention, interoception and sensory processing were thicker in meditation participants than matched controls. The thickness also correlated with meditation experience. The data found in this study provides the first structural evidence for experience-dependant cortical plasticity associated with meditation practice (Lazar et. al, 2005)

The video “How Does Meditation Change the Brain? – Instant Egghead #54” has some interesting insight into meditation and the brain.

[/tab]

[tab title=”Impacts of Meditation on Performance”]

There was a study done in 2008 which investigated the effects of Chan (Zen) meditation on musical performance anxiety and musical performance quality. Chan meditation is a disciplined practice that incorporates both concentration (samatha– calming the mind in Pali) and mindfulness (vipassana– insight into nature). This process is described as ‘silent illumination’ by Chan Masters since the 11th century. In the study, nineteen participants were recruited from music conservatories and randomly assigned to either an eight-week meditation group or a wait-list control group. Afterwards, all of the participants performed in a public concert. The outcome measures were performance anxiety and musical performance quality. Meditation practiced over a short term did not significantly improve musical performance quality. The control group demonstrated a significant decrease in performance quality with increases in performance anxiety. The meditation group demonstrated the opposite- a positive relation between performance quality and performance anxiety. This indicates that enhanced concentration and mindfulness, cultivated by Chan practice, might actually enable one to channel performance anxiety to improve musical performance. By cultivating nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment, the musicians learn to accept their anxiety and performance on the stage as it is. Although the change in performance quality may not be noticeable, the musicians learn to appreciate their performance, which leads to more self-satisfying performances (Lin, P., Chang, J., Zemon, V., & Midlarsky, E., 2008).

[/tab]

[tab title=”Mindfulness as Intervention”]

Psychological interventions that incorporate mindfulness and acceptance have been shown to be effective. In many areas such as depression, schizophrenia, or borderline personality disorder, psychologists have been advocating renewed attention to the importance of acceptance and mindfulness in the course of successful psychotherapy. The concepts of mindfulness and acceptance have been highlighted across theoretical schools of thought in modern psychology and they have been characteristics of Eastern philosophy for centuries (Lin, P., Chang, J., Zemon, V., & Midlarsky, E., 2008).

[/tab]

[/tabs]

It is important to note the complexity of the term ‘mindfulness’. As MMT has grown in popularity, a lot of variation has arisen in the way that mindfulness is conceptualized and in the trainings and interventions that have been included under this umbrella term (Van, Hobkirk, Sheppard, Aviles-Andrews, & Earleywine, 2014). It is important to differentiate the practices of mindfulness, meditation, yoga and the many variations and forms of these practices.

“Traditional teachings in the Theravada Buddhist tradition clearly differentiate the practices of compassion (karuna), loving kindness (metta), and other positive mind states associated with the Brahmavihara from the practice of mindfulness.” (Van, Hobkirk, Sheppard, Aviles-Andrews, & Earleywine, 2014).

So… after reading all of this information about yoga, meditation, and mindfulness, what can we learn from it? And, how can it be applied to our lives?

“Do all that you can, with all that you have, in the time that you have, in the place where you are.”—Nkosi Johnson (Hanson, & Mendius, 2009)

“Meditation cannot be the same for every man. Though the same in principle, namely, the steadying of the mind, the method must vary with the temperament of the practitioner”. (Besant, 2009).

I think it is especially important to recognize the complexity and individuality of these practices- absolutely everyone is different and the effects vary for each individual.

It is also worth noting that each individual musician has a different subjective perception of anxiety. One concept I find extremely interesting is the inseparability of mind and body – feelings represent one’s interpretations of bodily states, and emotional signals are derived from bodily states (Kenny, 2011). Techniques such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction address the mind and body as a whole.

Band grafitti. Wikimedia Commons

Meditation, by means of cultivating nonjudmental awareness, has been a proven way that musicians accept their anxiety and performance on stage as it is- bringing more self-satisfying performances (Lin, P., Chang, J., Zemon, V., & Midlarsky, E., 2008). I believe that achieving more self-satisfying performances, rehearsals, or practice sessions can be a huge step towards more self love for our playing, and a more positive self image. By bringing awareness to mindful practices, and introducing these methods, maybe we can help reduce stress and anxiety in musicians as well as create a healthier learning and working environment. If you are interested in reading more about meditation and its effects on musicians practice and performance, see the blog “The Art of Zen Music Playing“.

“The purpose of meditation is to learn to experience life fully as it unfolds – moment by moment. Through the practice of meditation, one can develop greater calmness, charity and insight in facing life’s experiences and in turning them into occasions for learning, and thus deepening one’s wisdom (Kabat-Zinn, & Santorelli, 1999).”

Perhaps Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), or a variation of this could be taught in schools in order to help students with their mental health and/or performance anxiety. A MBSR course usually includes basic relaxation and breathing techniques, meditation and simple yoga, along with homework such as maintaining a gratitude journal and a positive events log (Noonan, 2014).  Genesis. Wikimedia Commons

Genesis. Wikimedia Commons

If you wish to experiment yourself…

In daily life, you can explore basic meditation or mindfulness techniques as soon as you wake up, before you go to sleep, before your practice session, or even before a performance. An attitude of mindfulness can be interwoven with our practicing, performing, or attitude towards music.

Mindfulness and meditation are just a few options of ways to take care of our minds. It may not be right for everyone… so if you are interested in this topic or this way of thinking, you could do your own research and experiment in finding what works for you!

It is equally as important to care for our bodies as well as our minds, so that we may continue pursuing our job of of creating music in a creative and beautiful way.

“Science further verifies that when we cultivate compassion and mindful awareness in our lives – when we let go of judgements and attend fully to the present – we are harnessing the social circuits of the brain to enable us to transform even our relationship with our own self” -Buddha’s Brain (Hanson, & Mendius, 2009)

[accordion multiopen=”true”]

[toggle title=”References” state=”closed”]

Bibliography:

Austin, J. H. (2015). Zen and the brain: Toward an understand of meditation and consciousness. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Barbeau, A.-K. (2017). Is performing music soothing or stressful? Two perspectives: Music performance anxiety among musicians and the effect of active music-making on seniors’ health (doctoral dissertation). McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Besant, A. (2009). An introduction to yoga. Waiheke Island: Floating Press

Butzer, B., Ahmed, K., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2016). Yoga enhances positive psychological states in young adult musicians. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback : In Association with the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 41, 2, 191-202. doi:10.107/s10484-105-9321-x

Hanson, R., & Mendius, R. (2009). Buddha’s brain: The practical neuroscience of happiness, love, & wisdom. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Horan, R. (2009). The neuropsychological connection between creativity and meditation. Creativity Research Journal, 21, 2-3. doi:10.1080/10400410902858691

Kenny, D. (2011). Conceptual framework. In The Psychology of Music Performance Anxiety (pp. 15-32). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Khalsa, S. B. S., Shorter, S. M., Cope, S., Wyshak, G., & Sklar, E. (2009). Yoga ameliorates performance anxiety and mood disturbance in young professional musicians. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 34, 4, 279-289. doi:10.1007/s10484-009-9103-4

Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., McGarvey, M., … Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16, 17, 1893-1897. doi: 10.1097/01/wnr.0000186598.66243.19

Lehrer, P. M., Woolfolk, R. L., & Sime, W. E. (2007). Principles and practice of stress management. New York: Guilford Press.

Lin, P., Chang, J., Zemon, V., & Midlarsky, E. (2008). Silent illumination: a study on chan (zen) meditation, anxiety, and musical performance quality. Psychology of Music, 36, 2, 139-155. http://pom.sagepub.com

Noonan, S. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction. The Canadian Veterinary Journal = La Revue Vétérinaire Canadienne, 55, 2, 134-5.

Panesar, N., & Valachova, I. ( 2011). Yoga and mental health. Australasian Psychiatry, 19, 6, 538-539. doi:10.3109/10398562.2011.620613

Roy, M. M., Radzevick, J., & Getz, L. (2016). The manifestation of stress and rumination in musicians. Muziki, 13, 1, 100-112. doi:10.1080/18125980.2016.1182385

Van, D. N. T., Hobkirk, A. L., Sheppard, S. C., Aviles-Andrews, R., & Earleywine, M. (2014). How does mindfulness reduce anxiety, depression, and stress? An exploratory examination of change processes in wait-list controlled mindfulness meditation training. Mindfulness, 5, 5, 574-588. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1007/s12671-013-0229-3

Watson, A. H. D. (2009). Performance-related stress and its management. In The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury (pp. 332-352). Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

Media credits:

Band grafitti. Wikimedia Commons

Edvard Munch – The Scream. Wikimedia Commons

“How Does Meditation Change the Brain? – Instant Egghead #54”

“How stress affects your brain- Madhumita Murgia”

Limbic System, Wikimedia Commons

Suzanne-Valadon – The Violin Case, Wikimedia Commons

[/toggle]