The new phrase “Period jokes aren’t funny. Period” is a movement to give women respect about the fact that there are many “side-effects” to menstruation. In aiming to remove the sexist side of “PMS” jokes, women are reclaiming the scientific side of menstruation. There is still so often a taboo around discussing menstruation, and singing is no exception.

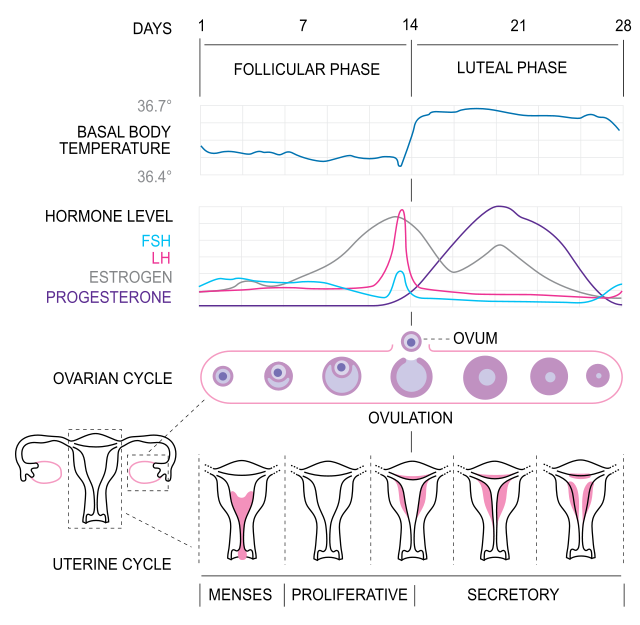

Before understanding what happens to the voice exactly, let’s look at the menstrual cycle itself.

Every body is different and there are many factors which can change this “typical” cycle. For the purposes of this blog, “healthy” cycles of 21-45 days with 3-7 days menstruation (called eumenorrhea) will be discussed.

[toggle title=”Want to know more about menstrual cycle hormones?”]

The menstrual cycle begins on the first day of menstruation.

The first half of the ovarian cycle is called the FOLLICULAR phase.

1) the hypothalamus (brain) releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) which is sent to the anterior pituitary gland (still brain!). Gonadotrophs are hormones targeted for the gonads: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). (In the testes, FSH is responsible for sperm production, and LH stimulates testosterone.)

2) the anterior pituitary gland releases FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) which travels to the ovaries and stimulates the growth of the ovarian follicles, which grow the ovum (egg). FSH also encourages the follicular cells to produce estrogen.

OVULATION typically happens around day 14, the middle of the cycle.

3) the anterior pituitary gland then gives bursts of LH (luteinizing hormone) which are also sent to the ovaries. These bursts increase until the level of LH is high enough to release the egg from the ovary. FSH, LH and estrogen are all at their highest points just before ovulation (see pink, blue and grey lines).

The second half of the ovarian cycle is called the LUTEAL phase.

4) once ovulation has occurred and the ovum is released, the follicle which released the egg begins to grow the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum’s main job is to produce and release hormones, which are necessary for the egg to successfully implant in the uterine lining. LH is what stimulates the corpus luteum to grow, and to produce progesterone.

5) Progesterone increases throughout the luteal phase, and is in charge of thickening the lining of the uterus. If the egg is fertilized and successfully implanted in the lining, pregnancy occurs. If it is not, the corpus luteum shrinks, and progesterone drops away (see purple line).

6) towards day 28, all the hormones are at their lowest point, and the endometrium drops, beginning menstruation and the cycle all over again (Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland, anatomy.tv).

Isometrik, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”How does the body know to release an egg?”]

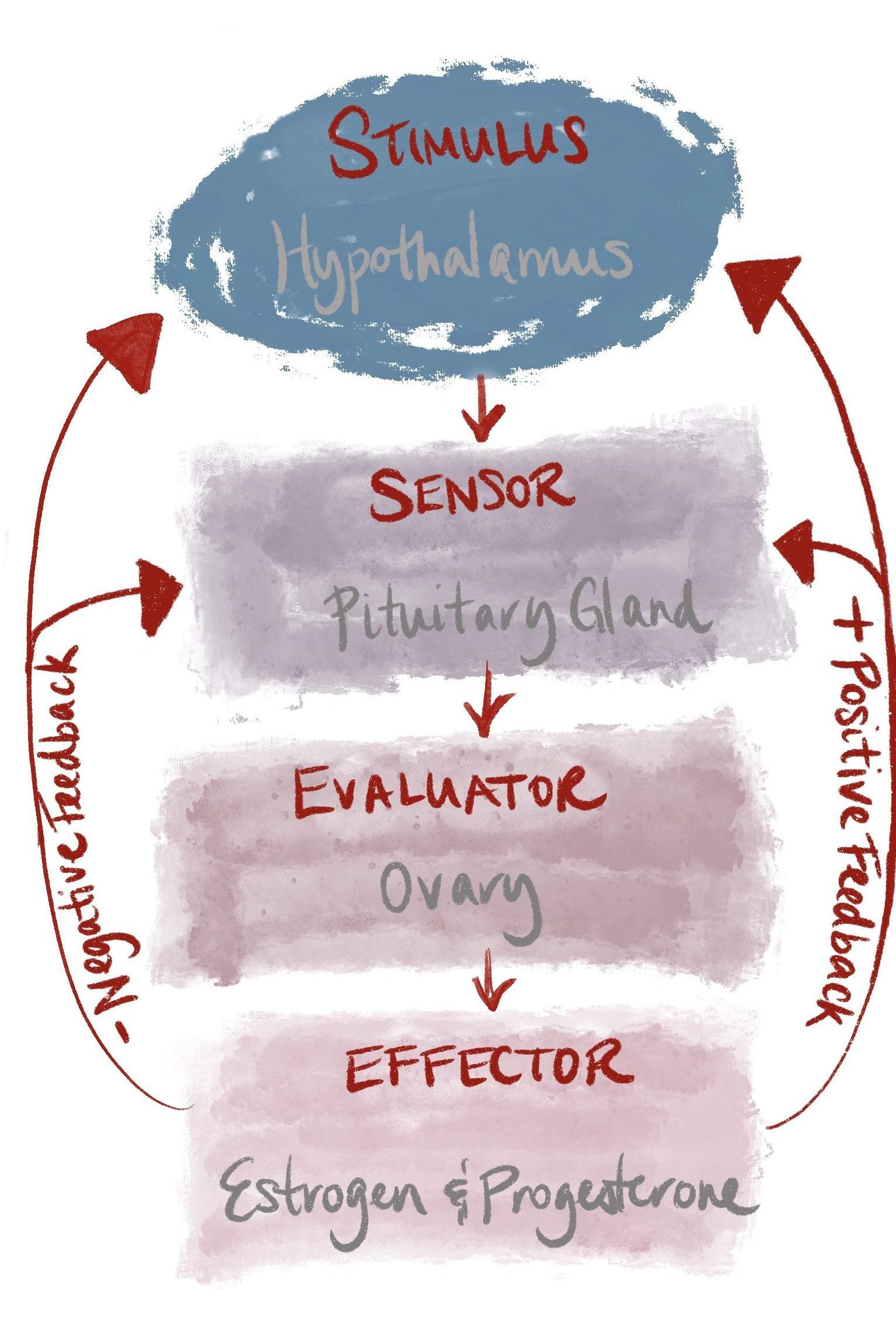

How does the body know when to release the egg? Using negative and positive feedback loops. Let’s use the above example.

The brain (hypothalamus) releases a hormone (gonadotropin) which stimulates another gland (the anterior pituitary gland) to secrete its own hormones (luteinizing hormone LH and follicle stimulation hormone FSH). FSH then travels down and stimulates growth in the ovaries.

The follicle in the ovary produces estrogen which then cycles back to the pituitary gland to tell it that it can stop the production of FSH (this is called the negative feedback loop).

Around days 12-14, the estrogen released also encourages the pituitary gland to release LH and more estrogen (positive feedback loop). When the LH peaks around day 14, the egg is released. Voilà! (Then repeat until menopause!)

[/toggle]

So… am I wrong? Or is my voice worse just before my period?

Premenstrual Syndrome, or PMS is a legitimate medical phenomenon. Sadly, it is too often treated as “a social construct which delegitimises, disempowers, and disenfranchises women, particularly with respect to women’s agency over their emotions and actions” (Kaye 2020, 60).

To start, let’s define the three main syndromes:

[infobox color=”#bcbcbc” textcolor=”#bf3a2b”]PMS – Premenstrual Syndrome[/infobox]

[toggle title=”What are the symptoms?”]

- Most common physical symptoms

- fatigue

- abdominal bloating

- acne

- change in appetite/cravings

- gastrointestinal upset

- headaches

- weight game

- Most common psychological/behavioural symptoms

- mood swings

- depression

- anxiety

- crying

- irritability

- problems concentrating

- social withdrawal

- forgetfulness

Medical criteria for PMS: no symptoms in follicular phase (before ovulation); must be ovulating (some women can experience PMS even after hysterectomy for example, if they still have ovarian function); multiple symptoms during the luteal phase (after ovulation); improvement of symptoms with menstruation; documentation of symptoms for two+ consecutive cycles; and symptoms which are severe enough to affect daily life/relationships (Danis et al. 2020, E9-10).

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”What helps?!”]

For general premenstrual syndrome symptoms, Harvard Health recommends the following:

- Exercise regularly, aim for at least 30 minutes most days of the week.

- Try to get a good night’s sleep. Avoid staying up all night.

- If you smoke, try to quit.

- Practice stress reduction techniques. Take a nice long bath or try meditation.

- Cut down on caffeine, alcohol, red meat and salty foods.

- Eat a balanced diet that is low in refined sugars.

- Do not skip meals. Follow a regular meal schedule to maintain a more stable blood sugar level (Harvard Health 2019).

- Studies show that skipping breakfast or reducing calories can make cramps worse (Kaye 2020, 62).

[/toggle]

[infobox color=”#c1c1c1″ textcolor=”#bc392b”]PMDD – Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder[/infobox]

A form of severe, debilitating PMS, especially with respect to emotional/behavioural symptoms. In rare cases, it can be accompanied by hallucinations or delusional behaviour. It is listed as a unique disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DMS).

[toggle title=”How do I know if I have this?”]

What makes this different from PMS?

- In the final week before menstruation, a total of at least 5 symptoms must be present, including:

- loss of interest in usual activities

- difficulty concentrating

- lethargy/marked fatigue

- overeating/specific food cravings

- change in appetite

- insomnia/hypersomnia

- feeling overwhelmed/out of control

- physical symptoms of breast tenderness/swelling

- joint/muscle pain

- weight gain/bloating

- At least one of the following additional symptoms must be counted in the total 5:

- marked irritability

- anger

- marked depressive mood

- hopelessness

- self-deprecating thoughts

- marked anxiety

- marked mood swings

- sensitivity to rejection

- sudden sadness or tears

(Danis et al. 2020, E11. Adapted from DSM 5th Ed. 2013.)

[/toggle]

[toggle title=”Antidepressants can help”]

Some studies have shown positive outcomes with low-dose and intermittent-dosing of SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitor, a type of antidepressants) in moderate to severe cases for people who don’t respond to non-pharmacologic therapies. SSRIs worked well for many psychological symptoms and some physiological. Doctors should prescribe the type of SSRI based on each individual. Intermittent-dosing studies do not report any issues with withdrawal, however the common side-effects of SSRIs remain the same: headaches, nausea, sexual dysfunction and sleep disturbances (Danis et al. 2020, E13).

The purpose of this information is to suggest that there are many therapies available, and that you should not have to suffer silently.

[/toggle]

► ACTION 1: If you experience any of the PMS or PMDD symptoms, talk with your doctor and begin tracking (documenting) your symptoms each cycle.

► ACTION 2: Research has suggested that changing diet can help, favour: high-fibre, vegetables, whole grains. Older studies suggest cutting back caffeine, but phew! a newer study did not have the same findings (Danis et al. 2020, E11). (But do keep drinking that water to combat de-hydration!)

► ACTION 3: Multiple studies have shown that calcium supplements can be very effective in relieving symptoms. Try asking to your doctor (Danis et al. 2020, E11).

[infobox color=”#c1c1c1″ textcolor=”#b73d2a”]PMVS – Premenstrual Vocal Syndrome[/infobox]

“…characterized by vocal fatigue, decreased range, a loss of power and loss of certain harmonics. The syndrome usually starts some 4-5 days before menstruation in some 33% of women” (Abitbol 1999, 424).

PMVS can also be called premenstrual dysphonia or laryngopathia premenstrualis:

- It affects 1/3 of menstruating singers

- Fluctuating hormones during the menstrual cycle cause laryngeal changes and lead to vocal impairments.

- PMVS only refers to vocal dysphonia.

- 50% of women who suffer PMS also suffer from PMVS.

- Vocal fatigue can set in after 25-30 minutes of singing.

- Clinical signs of PMVS are vocal fatigue; loss of range (especially high notes) and pianissimo; decreased vocal power; flat, colourless timbre; voice can be huskier or more metallic (Abitbol 1999, 437).

- Progesterone decreases arousal and activation levels in the body which could explain lower vocal intensity and lower airstream pressure during the luteal phase (Banai 2017, 9).

| Symptom of Premenstrual Syndrome | Effect on the Voice |

|---|---|

| Vocal folds are dry, have higher level of acidity and the laryngeal muscle has less tonicity due to increased progesterone | Dry, swollen vocal folds, less vocal amplitude (perceived as softer, lack of vocal strength) |

| All striated muscles lose tone – this includes vocal muscles, abdominal muscular belt and intercostal muscles | Reduces pulmonary power and vocal range. |

| Edema – in Reinke’s space and tissues of vocal folds (swelling) | Thick mucous (= more throat clearing) |

| Dilatation of microvarices (tiny veins) in the vocal folds | Could possibly rupture and form a hematoma on the fold (hematoma/hemorrhage = fatigued speaking voice, impossible to sing). |

| Increased acid reflux from relaxation of cardiac muscles | Can cause posterior laryngitis (swelling of a third of the vocal folds and stiff cricoarytenoid joints. |

| Inflamed nasopharyngeal mucosa (less common, according to Abitbol’s study) | Asymmetrical vocal fold vibrations, low amplitude (less vocal power) |

To sing or not to sing, that is the question!

In nineteenth century Europe, “grace days” were offered as time to rest while still getting paid (for example, La Scala Opera, Abitbol 1999, 438).

But, since we can’t cancel all our performances and stay in bed, what to do, what to do?

Talk about your questions and concerns with your voice teacher. Now that you know the menstrual cycle hormones can affect the voice, it is something to be discussed together. Even if you don’t experience strong symptoms of PMS, you might need to pay special attention to your vocal technique at these more fragile times.

Here are some tips for staying healthy…

[box title=”” align=”left”]Hydration. British Voice Association recommends to stay hydrated and well-rested during the luteal phase (also cutting on caffeine, salty and spicy foods, and dairy, which can be drying, and stimulate acid reflux and mucous) with 6-8 glasses of water a day (Kaye 2020, 62).[/box]

[box title=”” align=”left”]Vocal rest… Plan shorter, multiple practice sessions throughout the day if possible. Don’t wait until the voice is already strained and tired to “go on vocal rest”. Be proactive, pay attention to your stamina and energy levels! (Kaye 2020, 63).[/box]

[box title=”” align=”left”]Tylenol. It is interesting to note that singers are suggested to stay away from ibuprofen and aspirin as their anticoagulant properties could exacerbate the dilatation of microvarices (small veins) in the folds. Acetaminophen is favoured (Kaye 2020, 62). [/box]

[box title=”” align=”left”]Natural options. Calcium supplements (the most studied and seemingly beneficial); B6; Vitamin E or Magnesium supplements for various symptoms (with varying adverse effects). Acupuncture has also been suggested as a therapy for physical symptoms with no side effects (Danis et al. 2020, E15).

[box title=”” align=”left”]Get help. Talk to your doctor if you have strong symptoms of PMS, it is not always “just normal”, and perhaps help could be found.[/box]

Abitbol’s 1998 study suggests the following treatments for PMVS (Abitbol 1999, 439):

- the most responsive treatment was taking a multi-vitamin drug which has B5, B6, C, and PP; magnesium; anti-edema drugs (such as pineapple extracts).

- 1 week before menstruation, every month, taking anti-reflux and anti-allergy medications (ex. Claritin, Zyrtec) might be necessary.

- in extreme cases, estrogen therapy might be required, but is rare.[/box]

A hard pill to swallow…

A common prescription for PMS symptoms is the oral contraceptive pill (OCP). Studies are not conclusive though as to whether this intervention is healthy and helpful for the voice. It is important to note that oral contraceptive drugs have changed greatly over the years – progress has led to more effective pills with fewer side-effects on the voice.

Possible positive effects of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) for the voice:

- Low doses of OCPs help balance the hormonal fluctuations and also sometimes even out the vocal changes and instability experienced across the natural menstrual cycle (Kaye 2020, 61). If possible, singers should try to find physicians who are vocally aware when discussing the benefits of OCPs (Kaye 2020, 61).

- Interestingly, a sports study found that during the pre-menses period, athletes were more prone to errors which led to a higher rate of injuries. Players who took oral contraceptives were found to have fewer traumatic injuries (Reilly 2000, 34).

Possible “cons” to taking an oral contraceptive pill for the voice:

- It is also important to remember that OCPs have side effects, and some might be more adverse than the PMS symptoms. Nausea, breast pain, intermenstrual bleeding are examples of this (Danis et al. 2020, E16) and in rare cases, can lead to increased risk of blood clots (Kaye 2020, 62).

- Vocally, the biggest concern is that earlier generations of OCPs had some androgenic side effects. This means that the voice could permanently lower. Currently, in the latest-generation oral contraception, these effects are reduced. (Kaye 2020, 61)

- One study on pitch control during the menstrual cycle found that OCP users had difficulty with pitch control and vibrato on notes which required vocal control, like singing pianissimi or passaggio notes.

[infobox color=”#dbdbdb”]The pros and cons of oral contraceptive use must be discussed and weighed with your physician. Are your PMS symptoms severe and does your voice change a lot during your cycle? Does this bring you great stress? If so, perhaps OCPs could help. However, if the possible side effects out-weigh the need, it is likely not the right path to take.[/infobox]

So… let’s get you back to that stage! Take care of yourselves, ask questions, speak with your teachers and doctors, and let’s sing healthily and armed with support and knowledge!

[toggle title=”References”] Abitbol, J., Abitbol, P. & Abitbol, B. (1999). Sex hormones and the female voice. Journal of Voice, 13:3, 424-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0892-1997(99)80048-4.

Danis, P., Drew, A., Lingow, S. & Kurz, S. (2020, Jan. 1). Evidence-based tools for premenstrual disorders. The Journal of Family Practice, 69:1, E9-E17. EBSCO host.

Endocrine System. “Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland”. anatomy.tv.

Kaye, S. (2020). An overview of premenstrual voice syndrome: definition, treatment, and future trajectories. Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2020.1008.

Reilly, Thomas. (2000). The menstrual cycle and human performance: an overview. Biological Rhythm Research, 31 :1, 29-40. DOI: 10.1076/0929-1016(200002)31:1;1-0;FT029. [/toggle]

Leave a Reply