Is there an optimal approach to playing the string bass that minimizes tension, fatigue, and pain? What strengthening and stretching activities improve productivity while practicing and facilitate muscle recovery between playing sessions, rehearsals, and performances?

This blog will outline cross-training options for bassists, including warm-up exercises, nerve glides, and cool-down stretches. After explaining the structures and functions of the nervous and musculoskeletal systems (nerves, tendons, joints, muscles, and fascia), it will explain how specific exercises and stretches prepare the body for instrumental practice or performance and help it to recover afterwards. The blog concludes with links to short video demonstrations with verbal cues for each exercise or stretch.

Anatomy of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems: Joints, muscles, tendons, fascia, and nerves

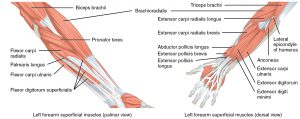

The first step in caring for oneself as a musical athlete is to distinguish between the different anatomical structures that work together to support and move our skeleton, including joints, muscles, tendons, fascia, and nerves. Joints are the spaces where ligaments attach bones together. Most skeletal muscles attach to bones via non-elastic tendons, which transmit the force of muscular contractions to the skeleton to move joints, like the deep forearm and hand muscles whose tendons attach to finger joints (Watson, 2009) (see Figure 1). For information about problems with tendons, see “Injuries of an alternate athlete.”

Figure 1. Deep forearm muscles (red) and tendons (white) (OpenStax, 1120 Muscles that move the forearm, CC BY 4.0).

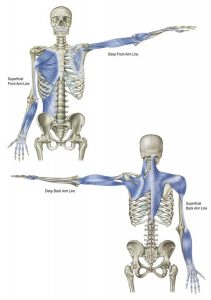

Each of these anatomical tissues differs in their structure and tensile properties. Tendons and ligaments are not elastic and therefore are not designed to stretch, whereas muscles have contractile properties that respond to regular stretching. Stretching counteracts the repeated concentric contractions involved in playing an instrument that shorten muscles over time with active eccentric contractions, which lengthen muscles, allowing for greater range of motion and flexibility. Beneath the skin and surrounding all skeletal muscles there are layers of fascia (Watson, 2009), a connective tissue that functions like shrink-wrap to connect muscle groups across the body. Healthy fascia moves freely around muscles and joints, and “is unrestricted to provide stability and structural support” (Meltzer et al., 2010). These layers of fascia in the body form fascial lines, which can be superficial, just beneath the skin surface, or deep within the body (Figure 2). The front arm lines connect both thumbs with the chest muscles, while the back arm lines connect both pinky fingers with the muscles of the shoulders and upper back.

Figure 2. The muscle groups of the four fascial arm lines (Basicmedical Key: The Arm Lines).

The remaining component in the anatomy of movement is the peripheral nervous system, which consists of nerves that exit from between each vertebrae of the spinal cord and travel along the extremities through small passages within joints to innervate specific tissues throughout the body, including the muscles and skin (Rosset i Llobet et al., 2007). Nerves contain bundles of both sensory and motor neurons. Sensory neurons detect sensations including pressure, shear, temperature, and pain, while motor neurons each activate a unique group of muscle fibers by transmitting an electrical signal from the brain and spinal cord, which make up the central nervous system (Watson, 2009). Of greatest interest to bassists are the three main nerves of the arm: the radial, median, and ulnar nerves. These three nerves originate in the brachial plexus, a bundle of nerves that exits from the cervical spine, passes along the collar bone, and goes through the shoulder. From there, the brachial plexus divides into the three branch nerves (radial, median, and ulnar), each of which passes through different spaces in the elbow and wrist to innervate separate areas of the arm and hand (see the yellow nerve pathways in Figure 3). Due to this circuitous route through the small passages within several joints, nerves are vulnerable to injury when these joints and the muscles and tendons that move them are compromised (Horvath, 2010). In order to prevent playing-related pain and injury, bassists need to care for all the structures in the musculoskeletal system, including fascia, muscles, joints, and tendons, as well as the nerves themselves.

The remaining component in the anatomy of movement is the peripheral nervous system, which consists of nerves that exit from between each vertebrae of the spinal cord and travel along the extremities through small passages within joints to innervate specific tissues throughout the body, including the muscles and skin (Rosset i Llobet et al., 2007). Nerves contain bundles of both sensory and motor neurons. Sensory neurons detect sensations including pressure, shear, temperature, and pain, while motor neurons each activate a unique group of muscle fibers by transmitting an electrical signal from the brain and spinal cord, which make up the central nervous system (Watson, 2009). Of greatest interest to bassists are the three main nerves of the arm: the radial, median, and ulnar nerves. These three nerves originate in the brachial plexus, a bundle of nerves that exits from the cervical spine, passes along the collar bone, and goes through the shoulder. From there, the brachial plexus divides into the three branch nerves (radial, median, and ulnar), each of which passes through different spaces in the elbow and wrist to innervate separate areas of the arm and hand (see the yellow nerve pathways in Figure 3). Due to this circuitous route through the small passages within several joints, nerves are vulnerable to injury when these joints and the muscles and tendons that move them are compromised (Horvath, 2010). In order to prevent playing-related pain and injury, bassists need to care for all the structures in the musculoskeletal system, including fascia, muscles, joints, and tendons, as well as the nerves themselves.

Figure 3. Radial, median, and ulnar nerves (Henry Gray, Nerves of the left upper extremity, public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons).

[toggle title=”Why does the human body protect nerves as its top priority? Why is fascia of fundamental importance in preventing musculoskeletal injuries?”]

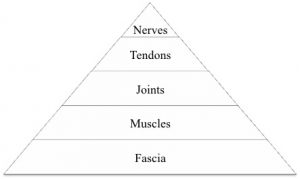

Table 1: The hierarchy of injury. Used with permission from Jennifer Hochnadel, PT DPT.

Why does the body protect nerves above all other tissues in the hierarchy of injury?

As vital communication lines within the body, nerves are the most well-protected of the tissues discussed above. Due to this priority status, any symptoms of referred nerve pain, tingling, numbness, or pins and needles are warning signs that a problem such as inflammation in one of the other tissues is affecting a nerve (Hochnadel, 2015). Unlike muscles and fascia, nerves do not respond well to stretching because they are easily irritated by increased muscle tension, joint compression, or friction from inflamed tendons (Rosset i Llobet & Odam, 2007). Stretching multiple joints in the arm to the extremes of their range of motion places the arm nerves under tension, which may aggravate symptoms of referred nerve pain in the forearm and hand. Nerve compression arises either from holding joints in a closed position for long periods of time, from a reduction in the mobility of nerves between bones due to accumulated muscle tension, or from swollen tendons due to inflammation, which decreases the space for nerves to pass through joints and increases friction and shearing when tendons slide past each other (Horvath, 2010). Nerves, therefore, are the capstone in the hierarchy of injury prevention because they can be compromised by problems with the fascia, muscles, tendons, or joints at any point along their path from the spine to the extremities (see Figure 3). Fortunately, a balanced combination of bodywork therapies can alleviate these problems and help bassists regain neural flexibility.

Why is fascia of fundamental importance in the prevention of musculoskeletal injuries?

Fascia forms the foundation of the Hierarchy of Injury because it links the extremities to the spine, uniting muscles, tendons, and joints with long lines of connective tissue that criss-cross the whole body. The process of myofascial release involves stretching or massaging entire fascial lines so that they gradually loosen their grip on the muscles they surround, allowing greater mobility and increasing blood flow to all the individual muscles in the fascial line (Rodríguez-Huguet et al., 2018). Due to the connective nature of fascia, accumulated tension in one joint may cause additional tension in a related area on the same fascial line (Rodríguez-Huguet et al., 2018). For example, fascial tension in the upper back reduces the mobility of the arm lines, leading to a less fluid transfer of movement from the back and core muscles to the forearms and hands, which then suffer from overuse as they take on more work. Releasing tension in the fascial arm lines (see Figure 2) has the potential to improve freedom of movement and reduce muscular tension throughout the extremities, as well as alleviating nerve compression within joints (see Figure 3). The exercises proposed below in this blog are based on the literature consulted (Rosset i Llobet & Molas, 2007; Rosset i Llobet & Odam, 2007; Horvath, 2010) and the author’s experience with bodywork modalities including Pilates, Tai Chi, and Iyengar Yoga. More research on the anatomy of fascial lines and the effects of myofascial release will contribute to further improvements in strategies for healthy strengthening and stretching for musicians (Wilke et al, 2016; Meltzer et al. 2010). [/toggle]

[toggle title=”Some helpful tips for injury prevention from an overview of surveys of playing postures and playing-related pain in bassists”]

Is there a relationship between musicians’ postures and their musculoskeletal complaints?

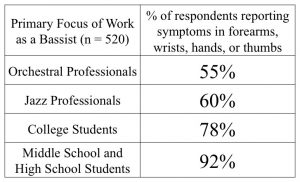

Though existing surveys of bassists are limited in generalizability, they attest to the widespread experience of pain that arises from playing the bass. A survey of symptoms and playing postures in 520 members of the International Society of Bassists (ISB) shows that playing-related pain and injuries are prevalent among professionals and students (see Table 2; Gilbert, 2009).

Table 2. Selected Results from “A Survey of, for, and about Bassists” (Gilbert, 2009).

Do the styles of music bassists play impact their levels of playing-related pain and injury?

The ISB survey also indicates that the locations of symptoms of pain, fatigue, and tension differ by the primary focus of bassists’ musical work, whether classical or jazz, as well as their bow hold. This study also inquired about the playing posture bassists chose, whether sitting, standing, or both in alternation (Gilbert, 2009). Despite the large survey sample size, the lack of statistical analysis limits the validity of these findings, which represent a collection of self-reported observations without establishing definite cause and effect relationships between certain techniques and specific symptoms. Bassists can still learn from the results of this survey by comparing their own experience with the compiled responses of peers in the same musical genre.

Does adopting extreme joint positions to play bass increase your chances of pain or injury?

A more recent cross-sectional study of 141 electric and acoustic bassists in conservatories and an orchestra in the Netherlands did not find statistical links connecting chronic pain, as measured by a self-reported survey, with the specific poor postures associated with each instrument (Woldendorp et al., 2016). These poor postures include a highly abducted left shoulder, which holds the left upper arm away from the body in acoustic bassists, and a highly flexed right wrist, which brings the right fingers around the instrument to pluck the strings in electric bassists (Woldendorp et al., 2016). This study also failed to establish a relationship between right wrist complaints and type of bow hold, either overhand French or underhand German (Woldendorp et al., 2016).

Does playing multiple types of bass instruments have a protective effect from pain/injury?

A second analysis of the same survey data revealed that multi-instrumentalism, or playing multiple instruments for at least one hour each day, did not have a protective effect on chronic pain complaints. Instead, multi-instrumentalists were 3.3 times more likely to experience left shoulder pain than mono-instrumentalists (Woldendorp et al., 2018).

Do surveys of bassists’ playing set-up and incidence of discomfort provide us with clear evidence of a link between playing postures and chronic pain?

These surveys demonstrate that despite their common occurrence, the relationship between musculoskeletal complaints and the specific postures bassists adopt when they play is unclear when measured through self-reported online surveys and statistical analysis alone.[/toggle]

[toggle title=”A summary of findings from previous muscle activation studies focusing on either electric or acoustic bassists”]

What can acoustic bassists learn from an existing scientific study of electric bassists?

Despite differences in playing set-up and the style of music played, research focused on electric bassists can offer insights for acoustic bassists, too. In a prior study of muscle activation and chronic pain in electric bass players, the same team of researchers did not find a link between muscle activation and self-reported pain complaints on surveys before and after a playing task (Woldendorp et al., 2013). The four target muscles included the trapezius muscles on either side of the neck and upper back (see muscle diagrams in “Optimal playing postures for violists”) and the radial wrist flexors (see the left side of Figure 4, Flexor carpi radialis) on the thumb side of the forearm during a continuous 30-minute chromatic blues cycle in all keys. The researchers acknowledged a variety of possible sources of interference in their data, including inconsistencies in the execution of the playing task on different instruments, the exclusion of unexpected pain survey responses, and individual variations in muscle activation patterns while playing (Woldendorp et al., 2013). A major limitation in the design of this study is the focus only on static postural muscles that hold the head and wrist in position while playing instead of the active muscles that move the fingers, hands, and arms to play. Future studies of both types of bass players need to account for over-worked small muscles in the extremities, unevenly used muscle groups on both sides, the front, and the back of the body, as well as the asymmetrical stresses and tensions on the large muscles of the torso.

Figure 4. Superficial forearm muscles (OpenStax, 1120 Muscles that move the forearm, CC BY 4.0).

How can studying muscle activation give us insights into the physicality of bass playing?

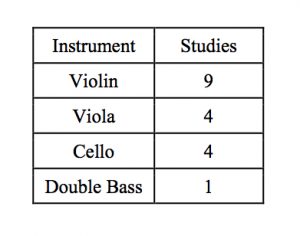

One of the main problems that upright bass players face is overuse or misuse of the small forearm and hand muscles in playing a large instrument, as well as sustained static loading on the large muscles that support either an upright posture while sitting asymmetrically on a stool or the weight of the bass while standing. Furthermore, there is a distinct lack of muscle activation studies focusing on the hands and forearms of acoustic bassists in comparison to other bowed string instruments (Kelleher et al., 2013).

Table 2. Studies of string players using surface electromyography (Kelleher et al., 2013).

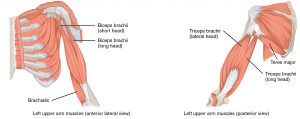

The sole study of muscle activation in double bass playing examined two separate techniques. The first portion investigated the rhythmic coordination of muscles in the shoulder (see right side of Figure 5, Teres major) and upper arm (see left side of Figure 5, Biceps brachii) to produce an even vibrato (Guettler, 1992). The second section compared the relative effort of two neck muscles (left and right upper Trapezius) when playing the same piece with the bass facing either forward like a cello or angled 20º to the right (Guettler, 1992). This early study proves that by measuring muscle activation in bass playing, it is possible to observe the physiological effects of different techniques on the muscles used for both playing actions such as vibrato and postural support in different set-up configurations. Further studies using this process may eventually lead to the development of targeted exercises and stretches that foster the development of self-care skills bassists need to sustain lifelong careers as performers.

Figure 5. Muscles of the upper arm (OpenStax, 1120 Muscles that move the forearm, CC BY 4.0).

[/toggle]

What does a musical athlete need to know in order to take efficient care of his or her body?

Similarly to athletes, musicians can approach practicing as training by integrating warm-up exercises, strategic breaks, and cool-down stretches into both practice sessions and performances. A review of studies of athletes shows that dynamic exercises before training and static stretches after training help to prevent muscular injuries by increasing circulation, neuro-conduction, and flexibility (Woods et al., 2007). In contrast to ballistic stretching, which involves repeated fast motions that tug on muscles, the slow, fluid motions of dynamic stretching are beneficial when incorporated into a warm-up routine before an athletic event (Opplert & Babault, 2018). These findings mean that the priority for musicians while training is to warm up before playing with movement exercises and dynamic stretches and to cool down afterwards with static stretching. These pre- and post-playing activities will also help to correct asymmetrical positions with the instrument by strengthening antagonist or opposing muscle groups and adopting specific counter postures that help rebalance the body. See the counterbalancing exercises demonstrated in the blog page “Pumping iron for prevention” for a strengthening training routine that benefits bass players when done every other day with light weights (0-3 lbs), low sets, and many repetitions. For example, one could start with 2 sets of 10 reps each on 3 days per week (Hochnadel, 2015). Musicians can integrate this order of operations into their daily schedule of activities by beginning with dynamic motion and ending with static release. This principle applies both on the small scale for before and after each practice session with the instrument and on the large scale in terms of the entire day, in which muscles need to move in the morning and then stretch before sleeping.

What is the difference between static rest and dynamic recovery during practice breaks?

Breaks from practicing are not necessarily enforced periods of absolute stillness. Practice breaks are an opportunity to integrate postural variety, counterbalancing exercises, and stretches that will offset the repeated positions and movements of playing the bass. Taking a walk or switching from sitting to standing are examples of varying posture during a break. One important form of movements that help provide postural variety are nerve glides, also called nerve flossing. Nerve glides refer to a group of movements that are neither muscular strength builders nor stretches. Instead, nerve glides involve slow, continuous dynamic motions through the comfortable range of motion of a nerve over its entire trajectory (all the joints from the neck to the wrist). These smooth moves are designed to gradually loosen compressed nerves through consistent daily repetitions over a two-week period from 3 to 5 sets of 10 repetitions per day as needed (Hochnadel, 2015). Given that the nervous system resets the plasticity of nerves (their freedom to move) after 20 minutes of staying in the same posture, it is essential to intersperse fixed positions and repeated movements with nerve glides and other postures during breaks (Hochnadel, 2015).

What counterbalancing exercises can assist bass players to correct asymmetrical postures?

Because of their forward-angled posture bass players often rely more on muscles in the front of the body than in the back, resulting in structural inequalities between strong chest muscles and weak back muscles. These asymmetries may be corrected through a process called reciprocal inhibition, which describes the relationship between muscles that oppose each-others’ respective actions in a particular movement. Reciprocal inhibition means that in order for an overly-strong agonist muscle to passively release and lengthen while being stretched, its weaker antagonist needs to actively contract in proportion. This concept provides the basis for the postural muscle strengthening exercises in“Pumping iron for prevention”. This principle differs from co-contraction (Woldendorp et al., 2013), in which both the agonist and antagonist muscles contract to a certain extent either to isometrically stabilize a joint (i.e. activating the Biceps and Triceps to hold the elbow at a right angle) or to perform the movements of playing (such as when both the flexors and extensors of the fingers activate when lifting and dropping fingers from the string). Therefore, the stretching exercises below address two goals by directly releasing contracted playing muscles and indirectly activating the antagonist postural muscles that are neglected while playing the bass.

Which other types of strengthening and stretching can help bassists to recover from intensive playing?

As musical athletes, bassists need to consider their practice habits, lifestyle choices, and physical activity levels in addition to the quantity and intensity of time they spend playing the bass. Cardiovascular exercise and various forms of body work such as yoga, Pilates, and Tai Chi can improve well-being, as long as the activity chosen does not stress joints in the arms that are already overused from bass playing (Rosset I Llobet, 2007, 97). These practices benefit musicians by improving neuroplasticity in the peripheral nervous system of the arms and upper body. Neuroplasticity refers to nerves’ freedom to move through all the joints in their path from the spine to the hands (Rosset I Llobet, 2007, 69). The Alexander Technique and Feldenkreis Method may also be useful to musicians because they assist in forming healthy postural habits and regaining full awareness of the entire body (Horvath, 2010, 88, 97). A key step for bassists to prevent overuse while practicing is “to take rest breaks before the onset of fatigue or pain” (Mandel, 1986). Avoid using the playing muscles to type or text during breaks from playing. Instead, breaks can incorporate active rest (lying down to let the spine release) and the recovery techniques described in this blog.

Author: Renaud Boucher-Browning

Please cite the author if referencing material from this blog.

[toggle title=”References”]

Articles

Gilbert, L. (2009). Results from ‘A survey of, for, and about bassists.’ Bass World: The Magazine of the International Society of Bassists, 33 (1), 29-33. Retrieved from http://isbconnect.org/results-from-survey-for-bassists/.WsQd_dPwauU

Guettler, K. (1992). Electromyography and muscle activities in double bass playing. Music Perception, 9 (3), 303-310. doi: 10.2307/40285554

Kelleher, L. K., Campbell, K. R., & Dickey, J.P. (2013). Biomechanical research on bowed string musicians: A scoping study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 28: 212-218. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259321634_Biomechanical_Research_on_Bowed_String_Musicians_A_Scoping_Study

Mandel, S., S. Patterson, & C. Johnson. (1986). Overuse syndrome in a double bass player. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 1: 133-34. Retrieved from https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/journalviewer.aspx?issue=1150&article=1499&action=1

Meltzer, K.R., T.V. Cao, J.F. Schad, H. King, S.T. Stoll, & P.R. Standley. (2010). In vitro modeling of repetitive motion injury and myofascial release. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 14 (2): 162-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2010.01.002

Opplert, J., & N. Babault. (2018). Acute effects of dynamic stretching on muscle flexibility and performance: An analysis of the current literature. Sports Medicine 48: 299–325. doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0797-9

Rodríguez-Huguet, M., J. L. Gil-Salú, P. Rodríguez-Huguet, J. R. Cabrera-Afonso, & R. Lomas-Vega. (2018). Effects of myofascial release on pressure pain thresholds in patients with neck pain: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 97: 16–22. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000790

Wilke, J., F. Krause, L. Vogt, & W. Banzer. (2016). What Is Evidence-Based About Myofascial Chains: A Systematic Review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97, 454-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.07.023

Woods, K., Bishop, P., & Jones, E. (2007). Warm up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injuries. Sports Medicine, 37 (12). 1089-1099. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737120-00006

Woldendorp, K.H., P. van de Werk, A. M. Boonstra, R. E. Stewart, & E. Otten. (2013). Relation between muscle activation pattern and pain: An explorative study in a bassists population. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94, 1095-1106. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.11.036

Woldendorp, K.H., A.M. Boonstra, A. Tijsma, J.H. Arendzen, & M.F. Reneman. (2016). No association between posture and musculoskeletal complaints in a professional bassist sample. European Journal of Pain, 20, 399-407. doi: 10.1002/ejp.740

Woldendorp, K. H., M. Boonstra, J. H. Arendzen & M. F. Reneman. (2018). Variation in occupational exposure associated with musculoskeletal complaints: A cross-sectional study among professional bassists. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 91 (2), 215-224. doi: 10.1007/s00420-017-1264-5

Books

Horvath, J. (2010). Playing (less) hurt: An injury prevention guide for musicians. New York: Hal Leonard.

Rosset i Llobet, J., & G. Odam. (2007). The musician’s body: A maintenance manual for peak performance. London: Guildhall School of Music & Drama.

Rosset i Llobet, J., & S. Fabregas Molas. (2007). L’entraînement physique du musicien. Collection médecine des arts. Montauban: Alexitère Éditions.

Watson, A. H. D. (2009). The biology of musical performance and performance-related injury. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Presentation

Hochnadel, Jennifer, PT DPT. (2015). Physical Therapy for Musicians. Guest Presentation for MUSI 503: Music and Performance: The Mind/Body Connection Course with Professor Janet Rarick. Shepherd School of Music, Rice University. Houston, TX. October 16, 2015.

Images

Figure 1. OpenStax, 1120 Muscles that Move the Forearm, CC BY 4.0

Figure 2. https://basicmedicalkey.com/the-arm-lines/

Figure 3. Henry Vandyke Carter Henry Gray, Nerves of the left upper extremity, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons

Figure 4. OpenStax, 1120 Muscles that Move the Forearm, CC BY 4.0

Figure 5. OpenStax, 1120 Muscles that Move the Forearm, CC BY 4.0

[/toggle]

Renaud. This is so cool. I really enjoyed reading it and learning from it. Rachel Venus

Hi Rachel, Thank you for reading this blog post. I glad to hear it was informative! Renaud